Messages from Late A-bomb Witnesses: Part 2: Messages in the 1990s and after

Dec. 9, 2010

Introduction

Cries from the soul must continue to be heard

Many late witnesses to the atomic bombing of Hiroshima have left behind words imbued with their wish for peace, powerful words that transcend time. “Messages from A-bomb Survivors” (originally published in 2001) is a two-part series which features the thoughts of notable figures whose words have appeared in the Chugoku Shimbun and in their writings.

Takeshi Ito: Co-chair of the Japan Confederation of A- and H-bomb Sufferers Organizations

However naïve, determined to continue conveying the A-bomb horror

Mr. Ito was president of the University of Yamanashi. He provided intellectual support to the movement seeking compensation from the Japanese government through the enactment of the Atomic Bomb Survivors Relief Law. At an international symposium in Hiroshima in 1977, he said:

“Humankind will be wiped out unless Hiroshima’s experience is conveyed to the entire human race. The participants of this event are part of the second wave of people, after the survivors of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, to convey the A-bomb experience. Please tell the world the reality of the devastation so the next generation will know what happened here.”

In 1998, though in ailing health, Mr. Ito gave an interview with the Chugoku Shimbun after India and Pakistan conducted back-to-back nuclear tests.

“We will continue to convey the terrible devastation of the atomic bombing through speech, writing, photos, and drawings. Some may call this naïve, but it’s the only thing we can do. The survivors are growing old. How many young people will pick up the torch from us, and pass it on? How can we motivate them, and teach them, to hand down our accounts? We are facing a host of challenges. We desperately need the people’s power and politics that will respond to our calls.”

Sakae Ito: Co-chair of the Japan Confederation of A- and H-bomb Sufferers Organizations

Peace must be won through action

“I want the Japanese government to burn incense for the A-bomb victims and apologize. I will never die until the government promises to provide compensation.”

Sakae Ito devoted herself to demanding national compensation through the realization of the Atomic Bomb Survivors Relief Law.

“Peace is not something you can bring about simply by praying,” she once said. “It is something you must win with action.”

During the Cold War between East and West in the 1970s and 1980s, Ms. Ito attended a United Nations Special Session on Disarmament and visited Europe and the United States to share her A-bomb account. Though she suffered pain in her legs and had difficulty walking, she traveled to Tokyo to meet lawmakers and government officials to demand that the Atomic Bomb Survivors Relief Law be adopted. When India and Pakistan conducted nuclear tests in 1998, she expressed anger and said, “If I were in good health, I would rush right there.”

Ms. Ito believed that no barriers posed by national borders or party differences should come between the A-bomb survivors. “We belong to the Human Party,” she said.

Heiichi Fujii: The first secretary general of the Japan Confederation of A- and H-Bomb Sufferers Organizations (Nihon Hidankyo)

“Restore things as they were.”

“‘Restore things as they were. If this is impossible, we at least want a relief law for the survivors.’ That was our hope.”

In 1981, marking the 25th anniversary of the founding of the Hiroshima Prefectural Confederation of A-bomb Sufferers Organizations, Mr. Fujii explained the hope with which the group had been established. He often spoke in Hiroshima dialect as he said, “Restore things as they were,” wishing the clock could be turned back on people’s lives, health, and property.

While ill in bed, he told a close friend that there was something he still had to do.

“I want an organization in Hiroshima that can be a global center which pursues work in three areas: comprehensive research on the damage caused by A- and H-bombs; a campaign against nuclear weapons; and treatment for the harm done by radiation.”

Masao Maruyama: Political scientist

“A-bombed people” should make a stronger appeal

“Now that Japan has lost everything because of the war, it can only contribute to peace in the world.”

Mr. Maruyama concluded a speech he made in Hiroshima in 1977 with these words. It was his first visit to the city in 32 years since experiencing the atomic bombing as a private first class in the Imperial Japanese Army.

Mr. Maruyama was a leading expert on the history of Japanese political thought. He served as a professor at the University of Tokyo and discussed issues of war and peace in a number of papers and books. At turning points in history, such as the Korean War and the conflict over the Japan-U.S. Security Treaty in 1960, Mr. Maruyama made statements and took action. But he rarely spoke about his A-bomb experience. A glimpse of the reason can be seen in a letter he wrote in 1983:

“I hate the Japanese climate (narcissism!) in which we lay bare and show off our own ‘experiences’ with such emotion. The harsher the A-bomb experience, the more I hate this.” (Quoted from the sixth issue of the “Maruyama Masao Techo,” a magazine featuring Mr. Maruyama’s thoughts and writings about him and his work by others.)

Rather, he sought to link the deep beliefs of the A-bomb survivors with various forms of the peace movement, based on each survivor’s A-bomb experience.

“Japanese citizens, with the duty of ‘A-bombed people,’ should assert themselves more and appeal more strongly to the international community,” Mr. Maruyama said.

Takeshi Araki: Former mayor of Hiroshima

Cenotaph inscription expresses spirit of Hiroshima

In 1980, when he was interviewed by the Chugoku Shimbun, Mr. Araki said: “Hiroshima and Nagasaki show the human race that the abolition of nuclear weapons is a prerequisite for the survival of our species, regardless of nationality, race, or ideology. I believe it is Hiroshima’s mission to make efforts to convey the experiences and the facts of the atomic bombing to the world in order to help address humanity’s common challenges, which include building international peace and bringing about the abolition of nuclear weapons.”

Mr. Araki visited the headquarters of the United Nations five times during the 16 years of his four terms in office to call for the abolition of nuclear weapons. In 1982, he addressed the United Nations Second Special Session on Disarmament and said:

“‘Let all the souls here rest in peace for we shall not repeat the evil.’ This inscription on the Cenotaph for the A-bomb Victims expresses the ‘spirit of Hiroshima,’ grounded in the humanitarian wish for the coexistence and prosperity of humankind.”

This summer, the World Conference of Mayors for Peace through Inter-city Solidarity, which was established in 1985, will hold its fifth general conference.

Ichiro Moritaki: Chair of the Japan Confederation of A- and H-Bomb Sufferers Organizations and the Japan Congress Against A- and H-Bombs

Sit-ins are a powerful form of protest

“‘Humankind must survive,’ I was murmuring without knowing it. But I wasn’t the only one murmuring this. I can hear the same murmuring from everywhere. This murmuring permeates every corner of the world.”

Professor Moritaki began with these words in an article he contributed to the Chugoku Shimbun in 1958. During his life, he made continuous efforts to advocate the absolute rejection of any form of nuclear activity and he sat in protest in front of the Cenotaph for the A-bomb Victims every time a nuclear test was conducted. In 1962, when he staged his first sit-in, he said:

“This is a critical time. We have carried out signature drives. We have held assemblies. We have sent letters of protest. Sit-ins are now the only means left for me. As a citizen of Hiroshima, it is my duty to end the vicious cycle of nuclear testing. I would like the people of Hiroshima to sit with me to protest nuclear testing, even for just an hour or 30 minutes.”

Professor Moritaki is known for the words “The chain reaction of spiritual atoms must prevail over the chain reaction of physical atoms.” In 1978, at his 100th sit-in, he said: “For A-bomb survivors and ordinary citizens who hold no power, sit-ins are a simple but powerful act to stand against nuclear authorities.”

Masanori Ichioka: Chair of the Hiroshima Prefectural Confederation of A-bomb Sufferers Organizations

Continued marching holds the power to stop war

“The real power to stop war is found in individuals who appear to be powerless but continue marching forward. We must not invite war by just standing idly by.”

In 1982, Mr. Ichioka wrote these words in an article for the Chugoku Shimbun, sharing why he took part in peace marches beyond the age of 60. The remorse he felt, as a teacher who lost students in World War II, served as the driving force for his commitment to peace education after the war.

Kiyoshi Sakuma: Head of the Japan Council against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs (Gensuikyo)

Fulfilled duty to preserve the A-bomb Dome

“So that scientific achievement won’t be used toward immoral ends, like the atomic bombs, it is vital that scientists are socially responsible and aware of their actions.”

Mr. Sakuma was exposed to the atomic bombing on the campus of Hiroshima University of Literature and Science (now, Hiroshima University) when he was an assistant professor at the Institute of Theoretical Physics there. In 1953, Mr. Sakuma and others, including a group of faculty members at universities in Hiroshima, formed a peace organization. It was a harbinger of the ban-the-bomb movement.

Though the ban-the-bomb movement splintered in 1963, eleven peace organizations banded together the next year to demand that the City of Hiroshima preserve the A-bomb Dome. Mr. Sakuma drafted the document stating this appeal.

“I was relieved when the decision was made to preserve the A-bomb Dome, thinking I was able to fulfill my duty to humanity.”

Iri Maruki and Toshi Maruki: Painters

Painting the A-bombing seen as destiny

“It is my destiny to paint the atomic bombing.”

In 1975, Iri looked back at his life with these words.

Toshi and Iri, who came upon the devastation of the A-bombing soon after she did, together created the well-known work “Hiroshima Panels.” In 1977, at the 10th anniversary of the Maruki Gallery for the Hiroshima Panels, located in Higashimatsuyama, Saitama Prefecture, Toshi said: “When it comes to the atomic bombing, there are still many paintings I would like to make. I expect my work will go on until the day I die.”

Shin Yong-Su: Chair of the South Korean Atomic Bomb Sufferers Association

Seeking compensation and an apology

“We are not asking for charity or begging for mercy. Japan has neglected us for the past 45 years, since the end of the war, and hasn’t provided us with adequate relief measures. We are demanding compensation, along with an apology, for all the damage to date.”

In 1990, a quarter of a century after the conclusion of the Treaty on Basic Relations between Japan and the Republic of Korea, Mr. Shin made this remark in an interview with the Chugoku Shimbun for a special feature entitled “Exposure: Victims of Radiation Speak Out.”

He continued to appeal to the Japanese and Korean governments for support for the Korean A-bomb survivors residing in South Korea. Meanwhile, he paved the way for bringing a group of visiting doctors from Japan and for sending Korean A-bomb survivors to Japan for treatment through nongovernmental exchange programs.

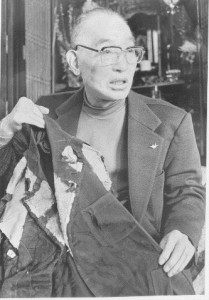

Busuke Shimoe: Board member of the Hiroshima Prefectural Confederation of A-bomb Sufferers Organizations

Speaking face-to-face conveys the truth

“Although people overseas know that the A-bomb’s heat rays and radiation wreaked horrific damage, they can’t understand this fully until they meet A-bomb survivors in person and hear what they have to say.”

Mr. Shimoe spoke these words prior to attending the first United Nations Special Session on Disarmament in 1978. He visited various places in Japan as well as overseas, including the former Soviet Union and the United Kingdom, and recounted his experience of the atomic bombing as he showed his burnt clothes from the time.

Tamotsu Eguchi: Head of association to support school trips to Hiroshima and Nagasaki

Education begins with the enthusiasm of teachers

“To live well, you must not ignore Hiroshima and Nagasaki,” said Mr. Eguchi in 1976 to his students at Kamihirai Junior High School in Tokyo about the significance of visiting Hiroshima on their school trip. This was the start of the “Kamihirai-style” school trips, in which students listen to A-bomb survivors in front of the Cenotaph for the A-bomb Victims.

Mr. Eguchi experienced the atomic bombing in Nagasaki. After his retirement in 1986, he moved from Tokyo to Hiroshima and established an association to support school trips to Hiroshima and Nagasaki. He was outspoken in pointing out needed improvements for receiving student visitors. He was also straightforward in admonishing teachers for their lack of enthusiasm. In 1993, he wrote:

“We will soon mark the 50th anniversary since that day. As A-bomb survivors are aging and dying, it is imperative that we listen to them and learn about their experiences and their thoughts. Only when teachers are earnest in learning from Hiroshima and show enthusiasm can they communicate something meaningful to their students. Education which arises from the thought that ‘Hiroshima is a teacher of the heart’ must begin with enthusiasm from our teachers.”

Ichiro Kawamoto: Leader of the Hiroshima Paper Crane Club

Wanting children in Hiroshima to develop their awareness

“Peace cannot be achieved through prayer or promises. We must work for it.”

In 1962, Mr. Kawamoto spoke with the Chugoku Shimbun about his early peace activities, which included his proposal to erect the Children’s Peace Monument; his founding of the Hiroshima Paper Crane Club in 1958 with children from elementary school through high school; and his launch of the campaign to preserve the A-bomb Dome.

Mr. Kawamoto was reserved in speech, but when insensitive critics said he was using children for his own aims, he responded:

“I only want children to do what they can and develop their awareness as citizens of Hiroshima. I have never forced them to do anything.”

Hatsuma Nagamatsu: Executive director of Yuda-en, a welfare center for A-bomb survivors

Afraid A-bomb accounts will not be handed down

“The survivors fear that, as they age, there are a dwindling number of people who can convey their A-bomb experiences. If these accounts aren’t handed down, the atomic bombing will fade from people’s consciousness. This is what I fear most, too.”

In an interview with the Chugoku Shimbun in 1975, Mr. Nagamatsu described the sense of crisis he felt over the fact that memories of the atomic bombing could disappear from people’s minds.

Driven by his anger toward the inhumanity of the atomic bomb, Mr. Nagamatsu became involved in supporting A-bomb survivors and the ban-the-bomb movement. He worked to form the Yamaguchi Prefectural Confederation of A- and H-Bomb Sufferers Organizations and to construct Yuda-en.

Shinobu Hizume: Board member of the Hiroshima Prefectural Confederation of A-bomb Sufferers Organizations

A-bomb experiences not being heard

“The horror of the atomic bombings is not well known. People seem to have never heard that people are still dying due to the atomic bombings, even ten years later,” said Ms. Hizume in 1955 at the Chugoku Shimbun. She was interviewed after returning to Japan from the United Kingdom and the former West Germany to share her experience of the Hiroshima A-bombing.

In 1970, Ms. Hizume joined a group of people who toured Hokkaido and other parts of Japan to call for the enactment of a relief law for A-bomb survivors. At that year’s World Conference against A- & H-Bombs, she said:

“When I went to Tohoku and Hokkaido, I realized that the A-bomb experiences aren’t being heard outside Hiroshima and Nagasaki. I’m very glad that I was able to talk about my experience in this way.”

(Originally published on August 1, 2001)