Chieko Ikeda, 84, Higashihiroshima City

Feb. 5, 2016

Terrible spectacle, with bodies cremated almost daily

by Hiroyuki Taniguchi, Staff Writer

On August 6, 1945, the day the atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, Chieko Ikeda (née Taomoto) was 13, a second-year student at today’s Yasu Elementary School in Asaminami Ward.

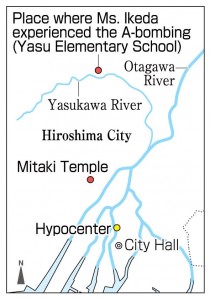

On that day, there were plans for the students to watch a movie at school, which she had been looking forward to. They were preparing for the movie in the school auditorium, located about nine kilometers from the hypocenter. As Ms. Ikeda stood near a window, there was a blinding flash, like a ball of fire streaking toward her. This was followed by a great boom. The bomb blast shattered the windows, sending broken glass onto her head. She had no time to don an air-raid hood.

She still remembers a boy reporting on what he saw from the vantage point of a nearby mountain, saying, “The whole city is a sea of flames.” The situation was very serious, she thought. When the black, radioactive rain fell in the aftermath of the blast, her white blouse was soaked black.

Before long, the wounded were fleeing from the city center, one after another. There were soldiers with eyeballs that had popped out, parents and children whose whole bodies were burned, and others who could not even be identified as male or female. It was a terrible spectacle. Schools and houses in the area took the wounded into their homes.

The older students of her school, including Ms. Ikeda, cared for the wounded alongside firefighters. But they had little medicine. All they could do was apply Mercurochrome or grated cucumber to the victims’ bodies. They used tweezers to remove maggots festering in their wounds. They kept up these efforts for days. “It was like a field hospital,” Ms. Ikeda said. “I wept as I cared for them.”

At one point someone grabbed her pair of monpe, traditional Japanese work pants, with a burnt hand, and begged for water. She still remembers the man’s voice. One mother who had been severely wounded asked her to hold her child and Ms. Ikeda clutched the little girl to her chest. But before long, both mother and daughter were dead.

As she was washing out bandages, crusty with pus, in the Yasukawa River that flowed in front of the school, she saw a man scoop up river water in his hands, take one or two sips, then collapse and die.

The bodies were cremated on nearby Shodenji Hill. Ms. Ikeda said, “Bodies were cremated almost every day, and there were a total of about 70. It was a dreadful sight.” Her school served as a first-aid station for about two months.

Back then, there were eight people in her family: her grandmother, her parents, her four siblings, and Ms. Ikeda herself. Her father was at his workplace in Sendamachi (now part of Naka Ward), and Ms. Ikeda, the second daughter in the family, went searching for him by herself on the evening of August 6. But she was frequently blocked by fire and gave up the search when she came to a bamboo grove near Mitaki Temple (now part of Nishi Ward). Fortunately, he returned home that night, despite suffering burns, and the members of her family did not sustain any severe injuries. But 12 years later, her sister, who was two years younger, passed away at the age of 23. Ms. Ikeda strongly suspects that this was due to the effects of radiation.

Ms. Ikeda suffered from chronic nosebleeds shortly after the atomic bombing and always carried tissues in her bag. When someone innocently asked why her nose bled so often, she was distressed. “I hated the atomic bomb,” she said, her voice straining with emotion. Fifty years after the bombing, she suffered a heart attack and skin cancer.

Her husband, Shotaro, who was also an A-bomb survivor, was in poor physical condition from his 30s until his death in 2006 at the age of 77. She helped her husband polish stones during the day and devoted herself to dressmaking at night despite her own poor health. Raising five children, she told herself, “I won’t give in to the atomic bombing. Winter always turns to spring.” She now has 25 grandchildren and 13 great-grandchildren.

Ten years ago, Ms. Ikeda moved to Toyosaka-cho in the city of Higashihiroshima, where her second son lives. After reaching the age of 80, she felt she should convey her experience to young people and began making efforts to do so. She sees this as a way of offering prayers for the repose of the dead. “War forces human beings to kill one another,” she said. “War must never be waged. Nuclear weapons are not needed.”

Teenagers’ Impressions

Taking responsibility for the future

Ms. Ikeda cried as she cared for the wounded and, many years later, she developed her own health problems, including skin cancer. But she said she didn’t lose hope to go on living. This made me feel that, even if we have hardships, we always have to keep our hope alive to go on. She told us, “I’ll leave the future to you.” With Ms. Ikeda’s words in mind, I want to take responsibility for shaping the future. (Tokitsuna Kawagishi, 14)

Helping to prevent the use of nuclear arms

Ms. Ikeda said that only those who were there at the time know what it was like to cremate bodies and know that smell. I can’t forget her quiet voice, telling us this. It’s true that all we can do is imagine what those conditions were like, but we would probably understand if a nuclear weapon is ever used. My power is small, but I want to continue this reporting work so such a thing won’t happen again. (Shiho Fujii, 14)

Appreciating our peaceful, everyday lives

Ms. Ikeda said, “The atomic bomb stole away so many lives and ended the happy futures of A-bomb survivors.” When I heard these words, I imagined how I would feel if I lived 70 years ago, and the fear of war grew and grew upon me. Ms. Ikeda also told us, “I want you to remember to feel grateful to your parents, and stand by them.” I thought how we have to value the everyday lives that we’re able to live in peace. (Marina Misaki, 16)

(Originally published on January 18, 2016)