Summer of President Obama’s visit to Hiroshima: 52 significant minutes, Part 5

Jul. 25, 2016

Part 5: Second-generation Japanese-American serves as bridge between two nations

by Michiko Tanaka, Staff Writer

Kazuaki Iwatake, 59, a resident of Tokyo and the eldest son of the late Nobuaki Iwatake, who had worked for the United States Embassy in Japan after the war, still remembers a simple comment made by his father when he was still alive. Nobuaki told his son that his combat uniform had no color, that it was “transparent.”

Nobuaki was a second-generation Japanese-American. His parents immigrated from Hiroshima to Hawaii, but he later returned from Hawaii to Japan and fought against the United States in the war after being drafted by the Japanese military. In addition, his younger brother was killed in the atomic bombing. His use of the word “transparent” expressed his hope for no more war between the United States and Japan.

For the ceremony in connection with U.S. President Barack Obama’s visit to Hiroshima on May 27, the U.S. government invited three people from families of war victims to attend, including Kazuaki. As he listened to President Obama speak, he thought of his late father’s life. “My father must have been very pleased, in particular, that this historic visit was made by President Obama,” he said.

Nobuaki was born and raised on the Hawaiian island of Maui as the eldest son of six children. After his father, who ran a grocery store, died suddenly in a water accident, he moved to Hiroshima, where he still had relatives, in June 1941. Six months later, the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, and war broke between Japan and the United States.

Friendship fostered on the battlefield

Wanting to avoid being drafted, Nobuaki enrolled in university. However, the Japanese government began drafting university students to fight in 1943, when he was a student at Meiji University. He was then dispatched on a ship to Ioto (Iwo Jima Island), but when the transport vessel he was on was attacked and sunk, he ultimately landed on Chichijima Island.

There on the island he was tasked with helping the Japanese Navy monitor U.S. radio communications because of his proficiency in English. During that time he encountered a young American pilot, Warren Vaughn, who was a prisoner of war. Later, Nobuaki told his family stories about the pilot, with whom he developed a friendship. He said that he and Mr. Vaughn shared their personal lives, and that the pilot rescued him when he fell into a hole while walking outside on a moonless night. But the war abruptly ended their bond when Mr. Vaughn was beheaded in reaction to the U.S. invasion of the island in March 1945.

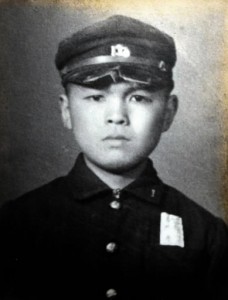

Another tragedy awaited him in Hiroshima when he returned to the city after the war. His youngest brother Takashi, 13 at the time and a first-year student at First Hiroshima Prefectural Junior High School (now Kokutaiji High School) was killed in the atomic bombing. His remains were found at the spot where the school building had stood in Zakoba-cho (now part of Naka Ward), identified only by his name on his trousers. Nobuaki dearly loved his brother, who had been studying hard to become a doctor, and he often wondered, even into his final years, what would have happened if Takashi had managed to survive. Nobuaki also paid many visits to Hiroshima with his family on August 6.

After the war, he worked for the Public Affairs and Culture Section of the U.S. Embassy in Tokyo for 34 years, after working at the Tokyo office of an American news outlet. During his career, Nobuaki called himself Warren Iwatake, adopting the name of the POW friend he had known on Chichijima Island. He assumed this name because he pledged that he would live on for his friend and make efforts to promote friendship between Japan and the United States.

Life torn between two homelands

While Nobuaki remained in Japan, his younger siblings decided to return to the United States and live there again. During the Korean War, his younger brothers joined the U.S. military, apparently to show their patriotism.

Kazuaki lived with his father until Nobuaki died in 2012 at the age of 88. “It must have been a struggle for my father, being Japanese-American during the war,” Kazuaki said, imagining how his father’s life was torn between two homelands. But watching his father work, he also felt that Nobuaki was proud to be a second-generation Japanese-American. He said, “I think he believed that he could be a bridge between Japan and the U.S. because he understood both the Japanese and American points of view.”

Ten years before his death, Nobuaki obtained a photo of Warren Vaughn and placed it in the living room of his home. A photo of Nobuaki is now displayed next to the photo of Mr. Vaughn.

(Originally published on July 25, 2016)