Survivors’ Stories: Ritsuko Ishikawa, 72, Nishi Ward, Hiroshima

Aug. 22, 2016

Loneliness of being an orphan was held inside

by Yuji Yamamoto, Staff Writer

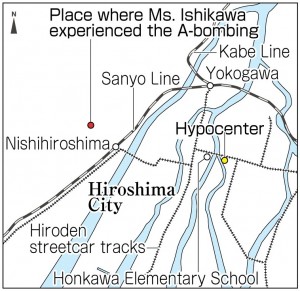

Honkawa Elementary School, located in Naka Ward, lies about 410 meters west of the A-bomb hypocenter. As a teacher at this school, Ritsuko Ishikawa, 72, was startled to see the nearby Atomic Bomb Dome from the school grounds in the summer of 1991. Her father must have seen this sight, she thought.

Ms. Ishikawa’s father, Sadamu, was a teacher at Honkawa National School, which preceded Honkawa Elementary School. He was 30 years old when he perished in the atomic bombing. When Ms. Ishikawa eyed the dome, and imagined how her father once gazed upon the same building, she wept without end because it was the first time she truly connected to her father’s life.

Ms. Ishikawa has no memories of her father because she was just a year old when Hiroshima was attacked. She was at home in Koi-cho (now part of Nishi Ward), about 3.5 kilometers from the hypocenter, and was exposed to the bomb’s radiation. According to her grandmother, Kinu, who was there with her, the sky suddenly lit up and there was a tremendous blast. They rushed into a nearby air raid shelter. Kinu died in 1976 at the age of 84.

Her mother, Toshiko, and her two-year-old sister, who were also at home, survived the blast, too. Her younger sister, born five days before the bombing, was blown into the air while in her baby bed, but suffered no harm.

Three days later, her grandmother ventured to the school to search for Ms. Ishikawa’s father, but was unable to find him. She subsequently learned that he had gone to the Hiroshima Post Office, located near the hypocenter, with a group of mobilized students. Ms. Ishikawa can still hear her grandmother’s voice, recalling, “I couldn’t find him.”

Ms. Ishikawa remembers, from around the age of three, streaks of black rain that were still visible on the inside walls of their home. She saw these eerie stains whenever she looked at the clock on the wall.

In 1953, when she was a third grader at Koi Elementary School, her mother, who had been prone to illness after experiencing the atomic bombing, passed away at the age of 33. She became an orphan, and was raised by her grandmother, who told her, “Just imagine that your parents are away.” Ms. Ishikawa held her loneliness inside, but when carnations were given to the students at school on Mother’s Day, the fact that she had lost her own mother hit home.

At the time, professors at Hiroshima University, including Ichiro Moritaki, were promoting the “moral adoption” campaign for A-bomb orphans. Yoko Kawasaki, a resident of Kyoto, who became a foster parent to Ms. Ishikawa when she was a sixth grader, was a fashionable woman and Ms. Ishikawa looked up to her. With the 1,000 yen sum that was sent to her by Ms. Kawasaki each month, Ms. Ishikawa was able to continue her studies, graduating from Kogo Junior High School, Kokutaiji High School, and Hiroshima University of Commerce (now Hiroshima Shudo University). Ms. Kawasaki passed away in 2013 at the age of 86.

For many years, Ms. Ishikawa never saw a picture of her father because her mother had burned all of them after the war. Finally, in 1990, after becoming a teacher at Honkawa Elementary School, she saw a photo of her father for the first time in a publication to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the school. Still, the image only showed his appearance and the fact that this man was her father did not really register. However, the following summer, when she was moving to a classroom, she looked at the A-bomb Dome and the realization hit with full force.

Then, in 1999, when she was a principal at Koi Elementary School, she found a collection of essays about A-bomb experiences in the school’s storeroom. They were written by 34 students six years after the atomic bombing. The life-changing experiences of August 6, 1945 were revealed in these essays, such as the words: “Evening has come, but my father has not come home yet.” The school’s peace memorial ceremony, held every August 6, was begun in 2000 in response to a proposal from a student who was copying the essays.

On the day of her retirement, in March 2004, she spoke to her late father in front of the family’s Buddhist altar, telling him that she had completed her work without incident. During her 32 years as an educator, she believes that none of the students under her care lost their lives to an accident or to illness because her father had been watching over them.

In 2012, she began to share her A-bomb account more actively after talking about her experience during an around-the-world voyage organized by Peace Boat, a Japanese non-profit organization. Now she speaks to students at preschools and elementary schools while showing drawings that she made herself.

“Nuclear weapons violently steal away parents from their children,” she said. “I want people in Hiroshima to use their own words to convey what they feel about peace. They need to use all their powers of persuasion because others may have different ideas.”

Teenagers’ Impressions

Moved by A-bomb essays written by children of my age

When I heard that students at Koi Elementary School were moved by the collection of essays written by A-bomb survivors who had been at the school earlier, I remembered Natsgumo (Summer Cloud), a collection of essays about A-bomb experiences written by graduates of my school and their parents. I hadn’t read it in a long time and when I did, I was moved by the passages written by those who experienced the atomic bombing when they were around the same age as me. I felt the joy of being alive and the importance of a world without war. (Yoshiko Hirata, 15)

Struck by the strength she showed in her life

Ms. Ishikawa was an orphan, but she said she didn’t feel any special hardships. After the war, everyone was just trying to survive and she said she felt rather fortunate. I was struck by the way she lived her life, with strength and optimism. As I listened to her story, I thought of my grandmother, who’s of the same generation as Ms. Ishikawa. I respect both women, who lived powerful lives. I felt encouraged by her and recognized the preciousness of life. (Anna Primus, 14)

Conveying the importance of a peaceful world

Ms. Ishikawa told us that it’s important to talk about the memories of the atomic bombing. But if we don’t know the facts, we can’t talk about the war and the atomic bombing in our own words. Now I serve as a High School Peace Ambassador and I have opportunities to meet people in and out of Japan. I want to learn more about the reality of the atomic bombing and actively tell others about it. I have reaffirmed my determination to convey the horror of the war and the atomic bombing and the importance of a peaceful world. (Miyuu Okada, 15)

(Originally published on August 22, 2016)

by Yuji Yamamoto, Staff Writer

Honkawa Elementary School, located in Naka Ward, lies about 410 meters west of the A-bomb hypocenter. As a teacher at this school, Ritsuko Ishikawa, 72, was startled to see the nearby Atomic Bomb Dome from the school grounds in the summer of 1991. Her father must have seen this sight, she thought.

Ms. Ishikawa’s father, Sadamu, was a teacher at Honkawa National School, which preceded Honkawa Elementary School. He was 30 years old when he perished in the atomic bombing. When Ms. Ishikawa eyed the dome, and imagined how her father once gazed upon the same building, she wept without end because it was the first time she truly connected to her father’s life.

Ms. Ishikawa has no memories of her father because she was just a year old when Hiroshima was attacked. She was at home in Koi-cho (now part of Nishi Ward), about 3.5 kilometers from the hypocenter, and was exposed to the bomb’s radiation. According to her grandmother, Kinu, who was there with her, the sky suddenly lit up and there was a tremendous blast. They rushed into a nearby air raid shelter. Kinu died in 1976 at the age of 84.

Her mother, Toshiko, and her two-year-old sister, who were also at home, survived the blast, too. Her younger sister, born five days before the bombing, was blown into the air while in her baby bed, but suffered no harm.

Three days later, her grandmother ventured to the school to search for Ms. Ishikawa’s father, but was unable to find him. She subsequently learned that he had gone to the Hiroshima Post Office, located near the hypocenter, with a group of mobilized students. Ms. Ishikawa can still hear her grandmother’s voice, recalling, “I couldn’t find him.”

Ms. Ishikawa remembers, from around the age of three, streaks of black rain that were still visible on the inside walls of their home. She saw these eerie stains whenever she looked at the clock on the wall.

In 1953, when she was a third grader at Koi Elementary School, her mother, who had been prone to illness after experiencing the atomic bombing, passed away at the age of 33. She became an orphan, and was raised by her grandmother, who told her, “Just imagine that your parents are away.” Ms. Ishikawa held her loneliness inside, but when carnations were given to the students at school on Mother’s Day, the fact that she had lost her own mother hit home.

At the time, professors at Hiroshima University, including Ichiro Moritaki, were promoting the “moral adoption” campaign for A-bomb orphans. Yoko Kawasaki, a resident of Kyoto, who became a foster parent to Ms. Ishikawa when she was a sixth grader, was a fashionable woman and Ms. Ishikawa looked up to her. With the 1,000 yen sum that was sent to her by Ms. Kawasaki each month, Ms. Ishikawa was able to continue her studies, graduating from Kogo Junior High School, Kokutaiji High School, and Hiroshima University of Commerce (now Hiroshima Shudo University). Ms. Kawasaki passed away in 2013 at the age of 86.

For many years, Ms. Ishikawa never saw a picture of her father because her mother had burned all of them after the war. Finally, in 1990, after becoming a teacher at Honkawa Elementary School, she saw a photo of her father for the first time in a publication to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the school. Still, the image only showed his appearance and the fact that this man was her father did not really register. However, the following summer, when she was moving to a classroom, she looked at the A-bomb Dome and the realization hit with full force.

Then, in 1999, when she was a principal at Koi Elementary School, she found a collection of essays about A-bomb experiences in the school’s storeroom. They were written by 34 students six years after the atomic bombing. The life-changing experiences of August 6, 1945 were revealed in these essays, such as the words: “Evening has come, but my father has not come home yet.” The school’s peace memorial ceremony, held every August 6, was begun in 2000 in response to a proposal from a student who was copying the essays.

On the day of her retirement, in March 2004, she spoke to her late father in front of the family’s Buddhist altar, telling him that she had completed her work without incident. During her 32 years as an educator, she believes that none of the students under her care lost their lives to an accident or to illness because her father had been watching over them.

In 2012, she began to share her A-bomb account more actively after talking about her experience during an around-the-world voyage organized by Peace Boat, a Japanese non-profit organization. Now she speaks to students at preschools and elementary schools while showing drawings that she made herself.

“Nuclear weapons violently steal away parents from their children,” she said. “I want people in Hiroshima to use their own words to convey what they feel about peace. They need to use all their powers of persuasion because others may have different ideas.”

Teenagers’ Impressions

Moved by A-bomb essays written by children of my age

When I heard that students at Koi Elementary School were moved by the collection of essays written by A-bomb survivors who had been at the school earlier, I remembered Natsgumo (Summer Cloud), a collection of essays about A-bomb experiences written by graduates of my school and their parents. I hadn’t read it in a long time and when I did, I was moved by the passages written by those who experienced the atomic bombing when they were around the same age as me. I felt the joy of being alive and the importance of a world without war. (Yoshiko Hirata, 15)

Struck by the strength she showed in her life

Ms. Ishikawa was an orphan, but she said she didn’t feel any special hardships. After the war, everyone was just trying to survive and she said she felt rather fortunate. I was struck by the way she lived her life, with strength and optimism. As I listened to her story, I thought of my grandmother, who’s of the same generation as Ms. Ishikawa. I respect both women, who lived powerful lives. I felt encouraged by her and recognized the preciousness of life. (Anna Primus, 14)

Conveying the importance of a peaceful world

Ms. Ishikawa told us that it’s important to talk about the memories of the atomic bombing. But if we don’t know the facts, we can’t talk about the war and the atomic bombing in our own words. Now I serve as a High School Peace Ambassador and I have opportunities to meet people in and out of Japan. I want to learn more about the reality of the atomic bombing and actively tell others about it. I have reaffirmed my determination to convey the horror of the war and the atomic bombing and the importance of a peaceful world. (Miyuu Okada, 15)

(Originally published on August 22, 2016)