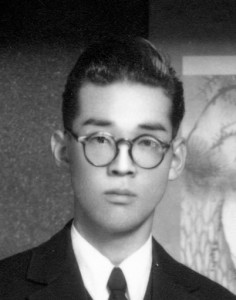

Survivors’ Stories: Masao Shimbata, 84, Hatsukaichi City

Sep. 19, 2016

Youth stolen away, left with damaged hand

by Rie Nii, Staff Writer

The war and the atomic bombing dramatically changed the life of Masao Shimbata, now 84. Both his parents died when he was young, and he was forced to stay with different relatives. He was unable to attend school, either. Even today, the injury he suffered to his left hand has made this hand harder to use. His youth was stolen from him, he says. Nevertheless, he carried on as best he could and managed to survive.

Mr. Shimbata’s father, a railroad worker, passed away from illness just three days before he was born. His mother, Kame, then raised her four children while working for the Japan National Railway in his father’s place.

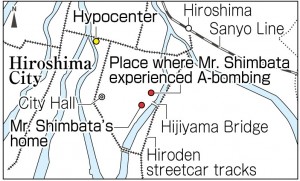

When Hiroshima was attacked with the atomic bomb, two brothers had already left home and were in the military. On August 6, 1945, Mr. Shimbata, who was 13 years old at the time, was absent from school and instead went to help work for the war effort with a neighborhood association in Showa-machi (now part of Naka Ward). Filling in for his mother, he pulled off roof tiles from homes that had been torn down to create a fire break. While performing this work in Tsurumi-cho (now part of Naka Ward and about 1.5 kilometers from the hypocenter), there was a sudden flash of light. He thought that soldiers were using dynamite to demolish a building, and that there was an accidental blast.

Mr. Shimbata was knocked unconscious and when he came to, there was darkness all around. Seeking to flee the area, he went groping over things in his path--whether they were logs or other things, he had no idea--and finally arrived at the west end of Hijiyama Bridge. Much to his relief, he was fortuitously reunited with his sister, Teruko, who was five years older.

Mr. Shimbata and Teruko hurried to the switchyard of the Japan National Railway, located on the east side of Hiroshima Station, to search for their mother, who they believed would be there. Electric wires and streetcar cables had fallen on the roads and were on fire. When he saw the Kyobashi River from Hijiyama Bridge, the water was so glutted with people seeking refuge that they could hardly move.

About that time, he began to feel a stinging pain, from burns suffered in the A-bomb blast, that ran from behind his right ear to the back of his neck and his right shoulder.

Mr. Shimbata and Teruko were then reunited with their mother, who had found safety in a railway passenger car, and the three walked to the Seno district (now part of Aki Ward), where his father’s parents lived. Along the way, they stopped at a first-aid station in the Yaga district (now part of Higashi Ward). Mr. Shimbata’s left elbow was bleeding and the first-aid workers removed bits of broken glass from his arm and closed the wound with three or four stitches.

They finally arrived in the Seno district around three or four o’clock the following morning. But there was no room at the house because the families of two aunts had already fled there. Seeing no other option, they set off for his maternal uncle’s home in the city of Kure.

At his uncle’s house, his suffering continued because of his burns and acute symptoms of radiation sickness, including hair loss and chronic nosebleeds. He remembers feeling sick when he found maggots wriggling in his flesh.

They stayed at his uncle’s house for about a month or two. They felt uncomfortable there because of unkind comments that were made and so moved to the house in the village of Hara (now the city of Higashihiroshima), where his mother had lived before she got married. They moved again, a month or two later, into company housing in the Funakoshi district (now part of Aki Ward) since they had relatives in that area.

When Mr. Shimbata’s grandmother told him that human bones could be helpful for burns, he went to his father’s tomb and took three or four bones from the urn. He then ground them into powder and applied this to his burnt skin. He felt that this eased the pain, but still spent more than a year at home because the burns would not heal. This also prevented him from attending school.

In December 1947, his mother was killed in a traffic accident and, three months later, his sister died of illness. In October 1948, with the help of his eldest brother, Tadayoshi, he joined the Teikoku Rayon Company (now Teijin Ltd.) and began to work at its factory in Mihara.

As the war intensified, children could no longer study. Mr. Shimbata explained, “We dug an air raid shelter on the school grounds and grew sweet potatoes in an empty section of the land. Apart from that, we only practiced fighting straw dummies with bamboo spears.” He tried to educate himself by reading a newspaper each day to compensate for the lack of schooling. Back then, he would read by guessing the meaning of unknown Chinese characters from the context of the article.

His left hand was badly damaged in the bombing, but he managed to hide this fact at a health checkup when he joined the company. At the factory, he sought to improve the company’s equipment for its work.

“Even if nuclear weapons are abolished, the consequences will be the same if war is waged. We have to abolish war, too,” he said. “We should value what we have now and live our lives without greed.”

Teenagers’ Impressions

Surviving after the A-bombing was so hard

What troubled Mr. Shimbata the most was that his home was burned down in the atomic bombing and he had no place to live. Even when his family fled to the homes of relatives, they weren’t able to stay there longer than two months and so had to move from house to house, which is hard to imagine now. I again realized how hard it was to survive the harsh conditions in Hiroshima, where everything was burned to the ground as a result of the bombing. (Felix Walsh, 14)

War, the cause of such sad fate, must end

Mr. Shimbata’s left hand was badly hurt in the bombing. His work was hampered by his hand, and his coworkers said unkind things to him. But he said, “It’s my fate.” I was really surprised that he didn’t blame this on the atomic bombing. I hope that war, which forces people to resign themselves to a fate like this, will never again take place. (Ai Mizoue, 14)

Young people must take over survivors’ activities

Mr. Shimbata said that he wants young people to take over the survivors’ activities. Because the A-bomb survivors are getting old, the day is approaching for us to assume these efforts. Many people who seek the abolition of nuclear arms have been working to eliminate these weapons. We may not be mature enough to take over these activities, but we want to do our best so that the survivors won’t worry when they pass on these efforts to us. (Harumi Okada, 17)

(Originally published on September 19, 2016)

by Rie Nii, Staff Writer

The war and the atomic bombing dramatically changed the life of Masao Shimbata, now 84. Both his parents died when he was young, and he was forced to stay with different relatives. He was unable to attend school, either. Even today, the injury he suffered to his left hand has made this hand harder to use. His youth was stolen from him, he says. Nevertheless, he carried on as best he could and managed to survive.

Mr. Shimbata’s father, a railroad worker, passed away from illness just three days before he was born. His mother, Kame, then raised her four children while working for the Japan National Railway in his father’s place.

When Hiroshima was attacked with the atomic bomb, two brothers had already left home and were in the military. On August 6, 1945, Mr. Shimbata, who was 13 years old at the time, was absent from school and instead went to help work for the war effort with a neighborhood association in Showa-machi (now part of Naka Ward). Filling in for his mother, he pulled off roof tiles from homes that had been torn down to create a fire break. While performing this work in Tsurumi-cho (now part of Naka Ward and about 1.5 kilometers from the hypocenter), there was a sudden flash of light. He thought that soldiers were using dynamite to demolish a building, and that there was an accidental blast.

Mr. Shimbata was knocked unconscious and when he came to, there was darkness all around. Seeking to flee the area, he went groping over things in his path--whether they were logs or other things, he had no idea--and finally arrived at the west end of Hijiyama Bridge. Much to his relief, he was fortuitously reunited with his sister, Teruko, who was five years older.

Mr. Shimbata and Teruko hurried to the switchyard of the Japan National Railway, located on the east side of Hiroshima Station, to search for their mother, who they believed would be there. Electric wires and streetcar cables had fallen on the roads and were on fire. When he saw the Kyobashi River from Hijiyama Bridge, the water was so glutted with people seeking refuge that they could hardly move.

About that time, he began to feel a stinging pain, from burns suffered in the A-bomb blast, that ran from behind his right ear to the back of his neck and his right shoulder.

Mr. Shimbata and Teruko were then reunited with their mother, who had found safety in a railway passenger car, and the three walked to the Seno district (now part of Aki Ward), where his father’s parents lived. Along the way, they stopped at a first-aid station in the Yaga district (now part of Higashi Ward). Mr. Shimbata’s left elbow was bleeding and the first-aid workers removed bits of broken glass from his arm and closed the wound with three or four stitches.

They finally arrived in the Seno district around three or four o’clock the following morning. But there was no room at the house because the families of two aunts had already fled there. Seeing no other option, they set off for his maternal uncle’s home in the city of Kure.

At his uncle’s house, his suffering continued because of his burns and acute symptoms of radiation sickness, including hair loss and chronic nosebleeds. He remembers feeling sick when he found maggots wriggling in his flesh.

They stayed at his uncle’s house for about a month or two. They felt uncomfortable there because of unkind comments that were made and so moved to the house in the village of Hara (now the city of Higashihiroshima), where his mother had lived before she got married. They moved again, a month or two later, into company housing in the Funakoshi district (now part of Aki Ward) since they had relatives in that area.

When Mr. Shimbata’s grandmother told him that human bones could be helpful for burns, he went to his father’s tomb and took three or four bones from the urn. He then ground them into powder and applied this to his burnt skin. He felt that this eased the pain, but still spent more than a year at home because the burns would not heal. This also prevented him from attending school.

In December 1947, his mother was killed in a traffic accident and, three months later, his sister died of illness. In October 1948, with the help of his eldest brother, Tadayoshi, he joined the Teikoku Rayon Company (now Teijin Ltd.) and began to work at its factory in Mihara.

As the war intensified, children could no longer study. Mr. Shimbata explained, “We dug an air raid shelter on the school grounds and grew sweet potatoes in an empty section of the land. Apart from that, we only practiced fighting straw dummies with bamboo spears.” He tried to educate himself by reading a newspaper each day to compensate for the lack of schooling. Back then, he would read by guessing the meaning of unknown Chinese characters from the context of the article.

His left hand was badly damaged in the bombing, but he managed to hide this fact at a health checkup when he joined the company. At the factory, he sought to improve the company’s equipment for its work.

“Even if nuclear weapons are abolished, the consequences will be the same if war is waged. We have to abolish war, too,” he said. “We should value what we have now and live our lives without greed.”

Teenagers’ Impressions

Surviving after the A-bombing was so hard

What troubled Mr. Shimbata the most was that his home was burned down in the atomic bombing and he had no place to live. Even when his family fled to the homes of relatives, they weren’t able to stay there longer than two months and so had to move from house to house, which is hard to imagine now. I again realized how hard it was to survive the harsh conditions in Hiroshima, where everything was burned to the ground as a result of the bombing. (Felix Walsh, 14)

War, the cause of such sad fate, must end

Mr. Shimbata’s left hand was badly hurt in the bombing. His work was hampered by his hand, and his coworkers said unkind things to him. But he said, “It’s my fate.” I was really surprised that he didn’t blame this on the atomic bombing. I hope that war, which forces people to resign themselves to a fate like this, will never again take place. (Ai Mizoue, 14)

Young people must take over survivors’ activities

Mr. Shimbata said that he wants young people to take over the survivors’ activities. Because the A-bomb survivors are getting old, the day is approaching for us to assume these efforts. Many people who seek the abolition of nuclear arms have been working to eliminate these weapons. We may not be mature enough to take over these activities, but we want to do our best so that the survivors won’t worry when they pass on these efforts to us. (Harumi Okada, 17)

(Originally published on September 19, 2016)