Survivors’ Stories: Hiromu Iwasaki, 79, Naka Ward, Hiroshima

Oct. 17, 2016

A-bomb perspective informed his work as a journalist

by Rie Nii, Staff Writer

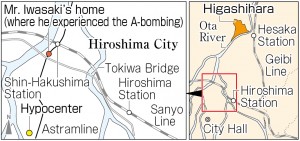

On the night of August 5, 1945, Hiromu Iwasaki, 79, returned to the city of Hiroshima from northeastern Okayama Prefecture, where he had evacuated earlier. He spent that night with his mother, Tamae, after some time apart. The next morning, the atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima. Mr. Iwasaki’s house was located about 1.3 kilometers from the hypocenter. “It’s like I came home only to experience the atomic bombing,” he said.

Mr. Iwasaki was eight years old at the time and a third grader at Hakushima National School (now Hakushima Elementary School in Naka Ward). Along with his sister, Mitsue, who was two years younger, he had been staying with his maternal grandparents in the city of Tsuyama after their evacuation from Hiroshima in April 1945. But during his summer break from school, on August 5, he returned home to Nishihakushima (now part of Naka Ward) with his grandfather, Soichi Kishimoto, after an eight-hour train ride on the Kishin and Geibi Lines.

Because the war was deteriorating badly, the Iwasaki family had decided to move everyone to Tsuyama, and on the morning of August 6, they were setting all their baggage outside the house in preparation for the move. Then, at the very moment he stepped into the entrance hall with his mother, Mr. Iwasaki heard the bomb’s deafening roar. The blast left him trapped under the wreckage of the one-story wooden house. Though pinned by a wall, he was eventually pulled out by his mother. His grandfather; his sister, Utako, four years younger; his brother, Yoji, six years younger; and his aunt, Mariko, were all in the house at the time, but they somehow managed to escape with only scratches.

Not long after, fires began to break out, here and there. Mr. Iwasaki retrieved some socks from a drawer and put them on his siblings’ feet. The group of six then fled north, along the banks of the Ota River, and continued walking to the designated evacuation site for the residents of the Nishihakushima district, located in Higashihara (now part of Asaminami Ward). That night, the family stayed in a private residence in Higashihara. It was around this time that Mr. Iwasaki started feeling some abdominal distress and was unable to eat anything for a while.

The next morning, Mr. Iwasaki gazed toward the city center and saw the whole area glowing bright red. He and his family then headed toward Hesaka Station (now part of Higashi Ward) to catch a train to Tsuyama. Some trains eventually came, but they were all crammed with people. Even trains that normally carried coal now contained passengers.

Mr. Iwasaki and his grandfather then managed to board a train. Because they had nothing to drink, they grew very thirsty on their journey to Tsuyama. He still remembers how he felt when he looked out the window of the train and saw water flowing down a mountainside; he wished he could have gotten off the train to drink from it. Finally, at around midnight, Mr. Iwasaki and his grandfather arrived in Tsuyama. The remaining four family members were able to get on the next train and, on the night of August 7, ended up sleeping outside at Miyoshi Station (now Nishi-Miyoshi Station in Miyoshi City).

Back then, Mr. Iwasaki’s father, Taichi, was part of the army corps of engineers. He experienced the bombing while at the military barracks located at the Hiroshima University of Literature and Science campus (now part of Naka Ward), about 1.4 kilometers from the hypocenter. He was blown through the air by the A-bomb blast, but luckily suffered no injuries.

In April 1946, after the war was over, Mr. Iwasaki returned to Hiroshima. In front of Hiroshima Station was a sprawling black market. In the river north of Tokiwa Bridge were still freight cars that had fallen off a railway bridge.

Mr. Iwasaki became a journalist after graduating from college. He said, “The many stories and experiences shared by the A-bomb survivors weren’t just someone else’s business. I think the things I wrote for the newspaper were imbued with the perspective of the A-bomb survivors.”

In May 2016, U.S. President Barack Obama became the first sitting U.S. president to visit Hiroshima and he stood in front of the Cenotaph for the A-bomb Victims, which contains the register volumes with the names of the A-bomb victims. The A-bomb Dome can be seen through the opening of the cenotaph. Mr. Iwasaki believes that Mr. Obama’s presence in front of the cenotaph is of great significance. He said, “I hope that the efforts made by the citizens of Hiroshima to overcome bitterness and hard feelings and make appeals for a peaceful world can help Mr. Obama take further steps toward a world without nuclear weapons.”

“War and nuclear weapons are the world’s biggest crimes,” he said. He hopes students in junior high and high school will listen to the experiences of many people and build up their knowledge in order to strengthen their capacity to judge things for themselves.

Teenagers’ Impressions

Impressed by will and strength to recover

I was amazed to learn that the national railway system began operating again only a day after the atomic bombing. Even streetcars in the city started running again three days after the attack. Because of this quick recovery, many people were able to board trains to escape the city and reach far-flung destinations in order to reunite with loved ones and flee the bomb’s radioactive fallout. I was really inspired by the will and the strength of the people to recover from such devastation. (Atsuhito Ito, 13)

Only sports should have winners and losers

“There are no winners or losers in the world other than in sports.” Mr. Iwasaki’s words reminded me of the Hiroshima Toyo Carp. The Carp, Hiroshima’s professional baseball team, were an ongoing source of encouragement and inspiration to the citizens of Hiroshima during the reconstruction of the city. Unlike sports, where players show respect for one another, in war, the one that kills and wounds the other becomes the winner. Mr. Iwasaki used these words to refer to war because he himself experienced the horror of war back then. (Riho Kito, 15)

Family reunion turns to misery

I was stunned by Mr. Iwasaki’s comment, “It’s like I came home only to experience the atomic bombing.” The atomic bomb instantly transformed the pure and innocent mind of a child, who felt relaxed and relieved during a family reunion after a long separation, into the nightmare of war’s cruelty. No nuclear weapons or wars should ever be permitted on this earth so that no one will ever again be forced to face such a brutal experience. (Marina Misaki, 17)

(Originally published on October 17, 2016)

by Rie Nii, Staff Writer

On the night of August 5, 1945, Hiromu Iwasaki, 79, returned to the city of Hiroshima from northeastern Okayama Prefecture, where he had evacuated earlier. He spent that night with his mother, Tamae, after some time apart. The next morning, the atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima. Mr. Iwasaki’s house was located about 1.3 kilometers from the hypocenter. “It’s like I came home only to experience the atomic bombing,” he said.

Mr. Iwasaki was eight years old at the time and a third grader at Hakushima National School (now Hakushima Elementary School in Naka Ward). Along with his sister, Mitsue, who was two years younger, he had been staying with his maternal grandparents in the city of Tsuyama after their evacuation from Hiroshima in April 1945. But during his summer break from school, on August 5, he returned home to Nishihakushima (now part of Naka Ward) with his grandfather, Soichi Kishimoto, after an eight-hour train ride on the Kishin and Geibi Lines.

Because the war was deteriorating badly, the Iwasaki family had decided to move everyone to Tsuyama, and on the morning of August 6, they were setting all their baggage outside the house in preparation for the move. Then, at the very moment he stepped into the entrance hall with his mother, Mr. Iwasaki heard the bomb’s deafening roar. The blast left him trapped under the wreckage of the one-story wooden house. Though pinned by a wall, he was eventually pulled out by his mother. His grandfather; his sister, Utako, four years younger; his brother, Yoji, six years younger; and his aunt, Mariko, were all in the house at the time, but they somehow managed to escape with only scratches.

Not long after, fires began to break out, here and there. Mr. Iwasaki retrieved some socks from a drawer and put them on his siblings’ feet. The group of six then fled north, along the banks of the Ota River, and continued walking to the designated evacuation site for the residents of the Nishihakushima district, located in Higashihara (now part of Asaminami Ward). That night, the family stayed in a private residence in Higashihara. It was around this time that Mr. Iwasaki started feeling some abdominal distress and was unable to eat anything for a while.

The next morning, Mr. Iwasaki gazed toward the city center and saw the whole area glowing bright red. He and his family then headed toward Hesaka Station (now part of Higashi Ward) to catch a train to Tsuyama. Some trains eventually came, but they were all crammed with people. Even trains that normally carried coal now contained passengers.

Mr. Iwasaki and his grandfather then managed to board a train. Because they had nothing to drink, they grew very thirsty on their journey to Tsuyama. He still remembers how he felt when he looked out the window of the train and saw water flowing down a mountainside; he wished he could have gotten off the train to drink from it. Finally, at around midnight, Mr. Iwasaki and his grandfather arrived in Tsuyama. The remaining four family members were able to get on the next train and, on the night of August 7, ended up sleeping outside at Miyoshi Station (now Nishi-Miyoshi Station in Miyoshi City).

Back then, Mr. Iwasaki’s father, Taichi, was part of the army corps of engineers. He experienced the bombing while at the military barracks located at the Hiroshima University of Literature and Science campus (now part of Naka Ward), about 1.4 kilometers from the hypocenter. He was blown through the air by the A-bomb blast, but luckily suffered no injuries.

In April 1946, after the war was over, Mr. Iwasaki returned to Hiroshima. In front of Hiroshima Station was a sprawling black market. In the river north of Tokiwa Bridge were still freight cars that had fallen off a railway bridge.

Mr. Iwasaki became a journalist after graduating from college. He said, “The many stories and experiences shared by the A-bomb survivors weren’t just someone else’s business. I think the things I wrote for the newspaper were imbued with the perspective of the A-bomb survivors.”

In May 2016, U.S. President Barack Obama became the first sitting U.S. president to visit Hiroshima and he stood in front of the Cenotaph for the A-bomb Victims, which contains the register volumes with the names of the A-bomb victims. The A-bomb Dome can be seen through the opening of the cenotaph. Mr. Iwasaki believes that Mr. Obama’s presence in front of the cenotaph is of great significance. He said, “I hope that the efforts made by the citizens of Hiroshima to overcome bitterness and hard feelings and make appeals for a peaceful world can help Mr. Obama take further steps toward a world without nuclear weapons.”

“War and nuclear weapons are the world’s biggest crimes,” he said. He hopes students in junior high and high school will listen to the experiences of many people and build up their knowledge in order to strengthen their capacity to judge things for themselves.

Teenagers’ Impressions

Impressed by will and strength to recover

I was amazed to learn that the national railway system began operating again only a day after the atomic bombing. Even streetcars in the city started running again three days after the attack. Because of this quick recovery, many people were able to board trains to escape the city and reach far-flung destinations in order to reunite with loved ones and flee the bomb’s radioactive fallout. I was really inspired by the will and the strength of the people to recover from such devastation. (Atsuhito Ito, 13)

Only sports should have winners and losers

“There are no winners or losers in the world other than in sports.” Mr. Iwasaki’s words reminded me of the Hiroshima Toyo Carp. The Carp, Hiroshima’s professional baseball team, were an ongoing source of encouragement and inspiration to the citizens of Hiroshima during the reconstruction of the city. Unlike sports, where players show respect for one another, in war, the one that kills and wounds the other becomes the winner. Mr. Iwasaki used these words to refer to war because he himself experienced the horror of war back then. (Riho Kito, 15)

Family reunion turns to misery

I was stunned by Mr. Iwasaki’s comment, “It’s like I came home only to experience the atomic bombing.” The atomic bomb instantly transformed the pure and innocent mind of a child, who felt relaxed and relieved during a family reunion after a long separation, into the nightmare of war’s cruelty. No nuclear weapons or wars should ever be permitted on this earth so that no one will ever again be forced to face such a brutal experience. (Marina Misaki, 17)

(Originally published on October 17, 2016)