Survivors’ Stories: Lee Jong Keun, 87, Asaminami Ward, Hiroshima

Nov. 7, 2016

South Korean A-bomb survivor endured dual discrimination

by Yuji Yamamoto, Staff Writer

“I suffered dual discrimination,” Lee Jong Keun, 87, said in a low voice. For much of his life, Mr. Lee hid two parts of his identity: being a second-generation South Korean in Japan and an A-bomb survivor. But when he made an around-the-world trip four years ago, in which he shared his account of the atomic bombing, he began talking about his life using his real name with the hope that the discrimination he experienced could be brought to an end.

Mr. Lee was born in Hikimi (now part of Masuda City) in Shimane Prefecture. Both of his parents were from the Korean Peninsula. At the age of one or two, he moved to the village of Yoshiwa (now part of Hatsukaichi City) in Hiroshima Prefecture. Then, in line with the Japanese government’s policy of pressuring Koreans to adopt Japanese names, a policy known as Soshi-kaimei which came into force in 1939, he began to identify himself as Masaichi Egawa.

He experienced Japan’s discrimination against Koreans first-hand. When he was a sixth-grade student at a national school (now elementary school), a neighbor called him “Korean” and made Mr. Lee stand before him. The man then urinated on the boy. At school, when a girl was crying, his teacher and classmates put the blame on him. “There was no option but to give in and endure the discrimination,” he said.

Afterward, he moved to the village of Saka (now part of Saka, Hiroshima Prefecture) and graduated from Yokohama National School (now Yokohama Elementary School). He landed a job at the engine depot of the Hiroshima Railway Bureau, work that he had wanted. But he hid the fact that he was a South Korean resident of Japan.

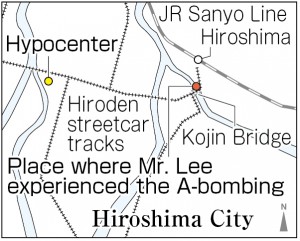

At the time of the atomic bombing, he was 15. He was on his way to work from his home in the village of Hera (now part of Hatsukaichi City) to his workplace in Higashikaniya-cho (now part of Higashi Ward). He had just gotten off the streetcar and crossed the Kojin Bridge near Hiroshima Station, about 1.8 kilometers from the hypocenter, when he was suddenly bathed in a yellowish light.

He covered his eyes, ears, and nose with his hands and dove to the ground. After a while, he lifted his head and found that it was now very dark all around him. He then waited until there was more light and he looked around. The lunchbox that he had brought with him, and placed at his feet, had been blown about 20 meters away. And he was unable to find his work cap and glasses. He didn’t realize he had suffered burns to his face, neck, hands, and feet until he fled for refuge under the bridge and was told that his face was red.

When he reached the engine depot, his coworkers were taken aback by his injuries and applied the black oil used for the locomotives to his burnt skin. It was so painful, he recalled, that he couldn’t help but cry. He then rested in the air-raid shelter there and left the depot around 4 p.m.

After walking about 16 kilometers, he finally arrived home at around 10 p.m. But his parents were out because they were looking for him. An hour later, his mother returned and shouted, “Oh my!” They held onto each other and wept. His father came back in the afternoon on the following day, but his sister went missing and was never found. She lived in the dormitory near the Army Clothing Depot (now part of Minami Ward), where she had been working.

For four months, until his burns began to heal, he feared he would die. Each day he tugged on his hair to see if it would fall out. He had maggots in the wounds around his neck.

One day during his ordeal, his mother was so distraught that she wished death would soon take him. She uttered these words, her tears dripping on his check, because she felt such sorrow for him. Mr. Lee was deeply moved by his mother’s compassion.

When Mr. Lee could finally return to work, a coworker told him that the others there could catch his “A-bomb disease.” This distressed him, and because he also felt uncomfortable hiding his South Korean identity, he quit working at the engine depot in 1946. He then made ends meet by selling recycled goods. He got married and had three daughters and, in the process, gradually set aside his memories of the atomic bombing.

In 2012, he was selected to join a group of A-bomb survivors on board a Peace Boat voyage that sailed around the world. During this trip he shared his A-bomb account on the ship and at ports of call. This was the first time he used his real name because he wanted others to be aware of the fact that people who were not Japanese also experienced the atomic bombing.

On this voyage, and a second voyage he made in 2014, he visited many places in the world including the Chernobyl nuclear power plant in Ukraine, the site of a major nuclear accident, and the former Auschwitz concentration camp in Poland, where many people of Jewish descent were murdered. Through these trips, he was able to again recognize the terror of nuclear energy and the tragedy brought about by racial discrimination. “All human lives are equal. War is foolish because it creates only sorrow,” he said. Mr. Lee now pins his hopes for the future on the world’s youth.

Teenagers’ Impressions

Understood importance of putting yourself in others’ shoes

We should never forget the fact that people who are not Japanese, like Mr. Lee, experienced the atomic bombing and also suffered as a result. Although I was aware of this, I didn’t really touch the reality until I had this chance to meet a non-Japanese survivor and listen to his story. His account shook me because what he experienced was beyond what I had imagined. I understood the importance of putting yourself into other people’s shoes and taking their experiences into account. (Miki Meguro, 13)

Need to recognize Japanese military's aggression, too

Mr. Lee said, “My relatives in South Korea told me that they were liberated thanks to the atomic bombings.” At first, I couldn’t believe this remark was made. The atomic bomb is an “absolute evil” because it kills people indiscriminately and causes long-lasting harm to human health. On the other hand, it’s also a fact that many people experienced terrible suffering as a result of invasions by the Japanese military. I realized that I need to know more about history of Japan’s aggression in order to appeal for nuclear abolition in the world. (Shunichi Kamichoja, 16)

Learn more about history to end war and discrimination

It was the first time for me to hear the account of an A-bomb survivor who’s a South Korean resident of Japan. I was surprised at the reality of racial discrimination that occurred during the war, and I’m also sad that this kind of discrimination is still carried out in the form of hate speech. Mr. Lee stressed that neither war nor discrimination would yield anything of value. I think it’s important that we learn more about history in order to realize a world without war or discrimination. (Haruka Shinmoto, 18)

(Originally published on November 7, 2016)

by Yuji Yamamoto, Staff Writer

“I suffered dual discrimination,” Lee Jong Keun, 87, said in a low voice. For much of his life, Mr. Lee hid two parts of his identity: being a second-generation South Korean in Japan and an A-bomb survivor. But when he made an around-the-world trip four years ago, in which he shared his account of the atomic bombing, he began talking about his life using his real name with the hope that the discrimination he experienced could be brought to an end.

Mr. Lee was born in Hikimi (now part of Masuda City) in Shimane Prefecture. Both of his parents were from the Korean Peninsula. At the age of one or two, he moved to the village of Yoshiwa (now part of Hatsukaichi City) in Hiroshima Prefecture. Then, in line with the Japanese government’s policy of pressuring Koreans to adopt Japanese names, a policy known as Soshi-kaimei which came into force in 1939, he began to identify himself as Masaichi Egawa.

He experienced Japan’s discrimination against Koreans first-hand. When he was a sixth-grade student at a national school (now elementary school), a neighbor called him “Korean” and made Mr. Lee stand before him. The man then urinated on the boy. At school, when a girl was crying, his teacher and classmates put the blame on him. “There was no option but to give in and endure the discrimination,” he said.

Afterward, he moved to the village of Saka (now part of Saka, Hiroshima Prefecture) and graduated from Yokohama National School (now Yokohama Elementary School). He landed a job at the engine depot of the Hiroshima Railway Bureau, work that he had wanted. But he hid the fact that he was a South Korean resident of Japan.

At the time of the atomic bombing, he was 15. He was on his way to work from his home in the village of Hera (now part of Hatsukaichi City) to his workplace in Higashikaniya-cho (now part of Higashi Ward). He had just gotten off the streetcar and crossed the Kojin Bridge near Hiroshima Station, about 1.8 kilometers from the hypocenter, when he was suddenly bathed in a yellowish light.

He covered his eyes, ears, and nose with his hands and dove to the ground. After a while, he lifted his head and found that it was now very dark all around him. He then waited until there was more light and he looked around. The lunchbox that he had brought with him, and placed at his feet, had been blown about 20 meters away. And he was unable to find his work cap and glasses. He didn’t realize he had suffered burns to his face, neck, hands, and feet until he fled for refuge under the bridge and was told that his face was red.

When he reached the engine depot, his coworkers were taken aback by his injuries and applied the black oil used for the locomotives to his burnt skin. It was so painful, he recalled, that he couldn’t help but cry. He then rested in the air-raid shelter there and left the depot around 4 p.m.

After walking about 16 kilometers, he finally arrived home at around 10 p.m. But his parents were out because they were looking for him. An hour later, his mother returned and shouted, “Oh my!” They held onto each other and wept. His father came back in the afternoon on the following day, but his sister went missing and was never found. She lived in the dormitory near the Army Clothing Depot (now part of Minami Ward), where she had been working.

For four months, until his burns began to heal, he feared he would die. Each day he tugged on his hair to see if it would fall out. He had maggots in the wounds around his neck.

One day during his ordeal, his mother was so distraught that she wished death would soon take him. She uttered these words, her tears dripping on his check, because she felt such sorrow for him. Mr. Lee was deeply moved by his mother’s compassion.

When Mr. Lee could finally return to work, a coworker told him that the others there could catch his “A-bomb disease.” This distressed him, and because he also felt uncomfortable hiding his South Korean identity, he quit working at the engine depot in 1946. He then made ends meet by selling recycled goods. He got married and had three daughters and, in the process, gradually set aside his memories of the atomic bombing.

In 2012, he was selected to join a group of A-bomb survivors on board a Peace Boat voyage that sailed around the world. During this trip he shared his A-bomb account on the ship and at ports of call. This was the first time he used his real name because he wanted others to be aware of the fact that people who were not Japanese also experienced the atomic bombing.

On this voyage, and a second voyage he made in 2014, he visited many places in the world including the Chernobyl nuclear power plant in Ukraine, the site of a major nuclear accident, and the former Auschwitz concentration camp in Poland, where many people of Jewish descent were murdered. Through these trips, he was able to again recognize the terror of nuclear energy and the tragedy brought about by racial discrimination. “All human lives are equal. War is foolish because it creates only sorrow,” he said. Mr. Lee now pins his hopes for the future on the world’s youth.

Teenagers’ Impressions

Understood importance of putting yourself in others’ shoes

We should never forget the fact that people who are not Japanese, like Mr. Lee, experienced the atomic bombing and also suffered as a result. Although I was aware of this, I didn’t really touch the reality until I had this chance to meet a non-Japanese survivor and listen to his story. His account shook me because what he experienced was beyond what I had imagined. I understood the importance of putting yourself into other people’s shoes and taking their experiences into account. (Miki Meguro, 13)

Need to recognize Japanese military's aggression, too

Mr. Lee said, “My relatives in South Korea told me that they were liberated thanks to the atomic bombings.” At first, I couldn’t believe this remark was made. The atomic bomb is an “absolute evil” because it kills people indiscriminately and causes long-lasting harm to human health. On the other hand, it’s also a fact that many people experienced terrible suffering as a result of invasions by the Japanese military. I realized that I need to know more about history of Japan’s aggression in order to appeal for nuclear abolition in the world. (Shunichi Kamichoja, 16)

Learn more about history to end war and discrimination

It was the first time for me to hear the account of an A-bomb survivor who’s a South Korean resident of Japan. I was surprised at the reality of racial discrimination that occurred during the war, and I’m also sad that this kind of discrimination is still carried out in the form of hate speech. Mr. Lee stressed that neither war nor discrimination would yield anything of value. I think it’s important that we learn more about history in order to realize a world without war or discrimination. (Haruka Shinmoto, 18)

(Originally published on November 7, 2016)