Survivors’ Stories: Hisao Kato, 87, Aki Ward, Hiroshima

Dec. 5, 2016

Lingering regret over not helping another after the A-bombing

by Yuji Yamamoto, Staff Writer

During Hisao Kato’s 37 years as a teacher, he sought to nurture students who could see the truth without being led astray by other influences. Mr. Kato, 87, was 16 years old and a fourth-year student at Shudo Middle School when he experienced the atomic bombing of Hiroshima. At the time he was doing what he could to contribute to the nation, believing that these efforts would help “make Asia a peaceful place.” Mr. Kato stressed the importance of looking back on this history objectively so that war will not be repeated.

In July 1944, Mr. Kato was mobilized to work at the Mitsubishi Heavy Industry Hiroshima Shipyard in Eba-machi (now in Naka Ward). His task involved punching holes in iron plates for use on the exterior of cargo ships. In the summer, the sun made the iron plates hot, raising the temperature at his work site. In the winter, he faced a cold wind from the sea, turning his fingers numb. Despite these conditions, he worked on earnestly, thinking that “Japan must win the war.”

On the morning of August 6, 1945, Mr. Kato was waiting for lessons to begin inside a wooden school building on the grounds of the shipyard. This was located about 4.2 kilometers from the hypocenter. At the time their work was suspended because of a shortage of iron. Suddenly, he was bathed in a red and yellow flash of light and his right cheek felt warm. He instinctively dove to the floor.

After the flash of light, which lasted for several seconds, a tremendous blast blew over his head. The roof of the school building was torn off and the glass panes of the windows shattered. He saw that his right arm was bleeding, perhaps cut by a piece of flying glass. But without pausing to give his arm attention, he dashed into a nearby air-raid shelter.

He waited there a while and then came out. The area around him was now dark and the city center, stretching before his eyes, was colored a yellow ocher. Mr. Kato was also astonished to see a gigantic gray cloud swirling up into the air like a dragon. “I was so stunned,” he said. “I had no idea what had happened.”

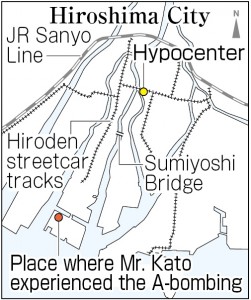

Around two o’clock that afternoon, he began heading home, by bicycle, with two friends. They were moving along the Honkawa River, but when they reached a place near the Sumiyoshi Bridge, they were unable to go farther because of raging fire from factories nearby. They went a different way, following the streetcar tracks, and kept moving north, finally reaching the Sumiyoshi Bridge. But then he got a flat tire and his friends went on without him. He grew even more anxious.

As he was pushing his bicycle and crossing the bridge, which was packed with people, he was approached by a woman who asked him to take her to a hospital. The woman’s face was black and her hair kinky from the bomb’s blast of heat. Mr. Kato, though, felt horrified by the sight and plodded past her. Even today, he still feels regret over his actions. “As a human being, I’m ashamed of what I did,” he said. “But I had no room in my heart right then to help others, when I didn’t even know if I could survive.” He continued on foot to his house in the village of Nakano (now part of Aki Ward), intently focused on getting home.

Mr. Kato’s younger sister was in her second year at Hiroshima Jogakuin Girls’ High School (now Hiroshima Jogakuin Junior High School) and she experienced the atomic bombing in Zakoba-cho (now part of Naka Ward) when she was mobilized to help tear down houses to create a fire lane. After returning home, she vomited. She then lost her hair and continued to suffer a high fever, but she eventually managed to recover her health. His elder sister, who was 18 and worked for the Hiroshima prefectural government, was thought to be near the Motoyasu Bridge at the time of the bombing, but her remains were never found.

The school resumed its lessons in September and continued the same type of education conducted during the war. But he noticed that when everyone at morning assembly was supposed to salute toward the east, in the direction of the Imperial Palace, one teacher, who taught Japanese history, would simply stand straight without saluting. Mr. Kato thought the teacher was “strange,” but he came to realize that the teacher was making this choice after mulling it over as an educator.

Although he took a job at the Hiroshima Labor Standards Bureau after graduation, he wanted to become a teacher, like that history teacher, and so he entered the fourth year of a high school program taught in the evening. He then studied in the Faculty of Education at Hiroshima University. In 1953, after graduating from college, he began teaching at junior high schools in Aki, Hiroshima Prefecture, a suburb of Hiroshima City, and at schools in Hiroshima City, where he taught social studies.

When using a chronological table in his history lessons, he would encourage his students to ponder not only the actions taken by powerful figures but the emotions shared by the ordinary people of that time. Since his retirement in 1990, he has shared his A-bomb experience in the Peace Memorial Park to convey to others the preciousness of human lives.

Mr. Kato said, “We were deceived by the nation and the powerful figures in the war. We must bring up people who can judge what is right and what is wrong.” Mr. Kato emphasized the role of education by reflecting on his boyhood days when people were imprinted with the idea that eventually the “the winds of god” would blow for Japan.

Teenagers’ Impressions

War threatens us with having to make a terrible choice

I thought over what I might decide when someone asks for help. In a peaceful time, I would help them or ask someone to assist me. But in conditions where I don’t know for certain if I myself would survive, I might leave without helping them, after apologizing. But I’m sure that such a decision would torment me, because I want to cherish my life and the lives of others, too. I really hate war, which could threaten me with having to make a choice between my life and someone else’s. (Atsuhito Ito, 13)

Remembering the importance of freedom and responsibility

During the war, and even after the atomic bombing, Mr. Kato didn’t think that Japan would lose the war. The war deprived people of their freedom of thought, and their lives, and made the nation’s victory the highest priority. I’m 15 years old and I mustn’t forget the fact that young people like me, who had a future, became imbued with the spirit of militarism and were sacrificed for the war effort. I’m determined to etch the importance of freedom and responsibility in my heart. (Hisashi Iwata, 15)

Need to maintain a critical perspective

Mr. Kato said, “I want children to become capable of seeing the truth.” With this thought in mind, he continued his work teaching children. Hearing this, I thought of the importance of maintaining a critical perspective. I’d like to make a habit of not simply accepting the opinions of others without question at school and at home. Rather, I want to think things over myself by reading books and taking in the opinions of my friends. (Naruho Matsuzaki, 16)

(Originally published on December 5, 2016)

by Yuji Yamamoto, Staff Writer

During Hisao Kato’s 37 years as a teacher, he sought to nurture students who could see the truth without being led astray by other influences. Mr. Kato, 87, was 16 years old and a fourth-year student at Shudo Middle School when he experienced the atomic bombing of Hiroshima. At the time he was doing what he could to contribute to the nation, believing that these efforts would help “make Asia a peaceful place.” Mr. Kato stressed the importance of looking back on this history objectively so that war will not be repeated.

In July 1944, Mr. Kato was mobilized to work at the Mitsubishi Heavy Industry Hiroshima Shipyard in Eba-machi (now in Naka Ward). His task involved punching holes in iron plates for use on the exterior of cargo ships. In the summer, the sun made the iron plates hot, raising the temperature at his work site. In the winter, he faced a cold wind from the sea, turning his fingers numb. Despite these conditions, he worked on earnestly, thinking that “Japan must win the war.”

On the morning of August 6, 1945, Mr. Kato was waiting for lessons to begin inside a wooden school building on the grounds of the shipyard. This was located about 4.2 kilometers from the hypocenter. At the time their work was suspended because of a shortage of iron. Suddenly, he was bathed in a red and yellow flash of light and his right cheek felt warm. He instinctively dove to the floor.

After the flash of light, which lasted for several seconds, a tremendous blast blew over his head. The roof of the school building was torn off and the glass panes of the windows shattered. He saw that his right arm was bleeding, perhaps cut by a piece of flying glass. But without pausing to give his arm attention, he dashed into a nearby air-raid shelter.

He waited there a while and then came out. The area around him was now dark and the city center, stretching before his eyes, was colored a yellow ocher. Mr. Kato was also astonished to see a gigantic gray cloud swirling up into the air like a dragon. “I was so stunned,” he said. “I had no idea what had happened.”

Around two o’clock that afternoon, he began heading home, by bicycle, with two friends. They were moving along the Honkawa River, but when they reached a place near the Sumiyoshi Bridge, they were unable to go farther because of raging fire from factories nearby. They went a different way, following the streetcar tracks, and kept moving north, finally reaching the Sumiyoshi Bridge. But then he got a flat tire and his friends went on without him. He grew even more anxious.

As he was pushing his bicycle and crossing the bridge, which was packed with people, he was approached by a woman who asked him to take her to a hospital. The woman’s face was black and her hair kinky from the bomb’s blast of heat. Mr. Kato, though, felt horrified by the sight and plodded past her. Even today, he still feels regret over his actions. “As a human being, I’m ashamed of what I did,” he said. “But I had no room in my heart right then to help others, when I didn’t even know if I could survive.” He continued on foot to his house in the village of Nakano (now part of Aki Ward), intently focused on getting home.

Mr. Kato’s younger sister was in her second year at Hiroshima Jogakuin Girls’ High School (now Hiroshima Jogakuin Junior High School) and she experienced the atomic bombing in Zakoba-cho (now part of Naka Ward) when she was mobilized to help tear down houses to create a fire lane. After returning home, she vomited. She then lost her hair and continued to suffer a high fever, but she eventually managed to recover her health. His elder sister, who was 18 and worked for the Hiroshima prefectural government, was thought to be near the Motoyasu Bridge at the time of the bombing, but her remains were never found.

The school resumed its lessons in September and continued the same type of education conducted during the war. But he noticed that when everyone at morning assembly was supposed to salute toward the east, in the direction of the Imperial Palace, one teacher, who taught Japanese history, would simply stand straight without saluting. Mr. Kato thought the teacher was “strange,” but he came to realize that the teacher was making this choice after mulling it over as an educator.

Although he took a job at the Hiroshima Labor Standards Bureau after graduation, he wanted to become a teacher, like that history teacher, and so he entered the fourth year of a high school program taught in the evening. He then studied in the Faculty of Education at Hiroshima University. In 1953, after graduating from college, he began teaching at junior high schools in Aki, Hiroshima Prefecture, a suburb of Hiroshima City, and at schools in Hiroshima City, where he taught social studies.

When using a chronological table in his history lessons, he would encourage his students to ponder not only the actions taken by powerful figures but the emotions shared by the ordinary people of that time. Since his retirement in 1990, he has shared his A-bomb experience in the Peace Memorial Park to convey to others the preciousness of human lives.

Mr. Kato said, “We were deceived by the nation and the powerful figures in the war. We must bring up people who can judge what is right and what is wrong.” Mr. Kato emphasized the role of education by reflecting on his boyhood days when people were imprinted with the idea that eventually the “the winds of god” would blow for Japan.

Teenagers’ Impressions

War threatens us with having to make a terrible choice

I thought over what I might decide when someone asks for help. In a peaceful time, I would help them or ask someone to assist me. But in conditions where I don’t know for certain if I myself would survive, I might leave without helping them, after apologizing. But I’m sure that such a decision would torment me, because I want to cherish my life and the lives of others, too. I really hate war, which could threaten me with having to make a choice between my life and someone else’s. (Atsuhito Ito, 13)

Remembering the importance of freedom and responsibility

During the war, and even after the atomic bombing, Mr. Kato didn’t think that Japan would lose the war. The war deprived people of their freedom of thought, and their lives, and made the nation’s victory the highest priority. I’m 15 years old and I mustn’t forget the fact that young people like me, who had a future, became imbued with the spirit of militarism and were sacrificed for the war effort. I’m determined to etch the importance of freedom and responsibility in my heart. (Hisashi Iwata, 15)

Need to maintain a critical perspective

Mr. Kato said, “I want children to become capable of seeing the truth.” With this thought in mind, he continued his work teaching children. Hearing this, I thought of the importance of maintaining a critical perspective. I’d like to make a habit of not simply accepting the opinions of others without question at school and at home. Rather, I want to think things over myself by reading books and taking in the opinions of my friends. (Naruho Matsuzaki, 16)

(Originally published on December 5, 2016)