Gray area: Effects of exposure to low-level radiation, Part 6 [1]

Sep. 23, 2016

Rethinking Fukushima

by Yumi Kanazaki and Yota Baba, Staff Writers

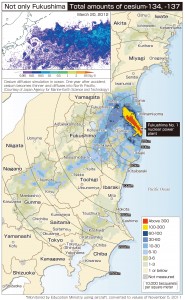

Five and a half years have passed since the accident at the Fukushima No. 1 (Daiichi) nuclear power plant, which spewed radioactive substances such as iodine and cesium over broad swaths of land and into the ocean. Health surveys carried out by the Fukushima prefectural government have found that 174 children either have or are suspected of having thyroid cancer. Studies on the natural surroundings have also been conducted. Have the effects of exposure to low-level radiation already manifested? Or will they show up in time? Scientific approaches are seeking to reveal the truth.

Differing views on incidence of thyroid cancer in children

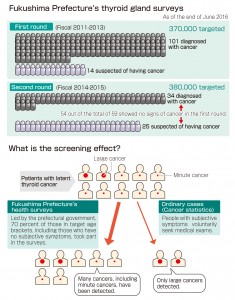

The health surveys carried out by the Fukushima prefectural government are aimed at discerning the health effects of the nuclear power plant accident. In 2011, the committee overseeing the surveys began performing ultrasound examinations on the thyroid glands of children who were 18 or younger at the time of the nuclear disaster. About 300,000 people, or 70 percent of this population, underwent the tests. So far, 135 are confirmed to have cancer that is malignant, and 39 are suspected of having cancer.

Some researchers regard this incidence as “plainly high,” considering the normal incidence of children’s thyroid cancer, an estimate based on statistics from different areas of the country which amounts to only a handful per million. The interim report compiled by the committee in March 2016 states that the incidence discovered is dozens of times higher when compared to other statistics for cancer.

On the other hand, many researchers support the view that the Fukushima data cannot be compared to cancer statistics compiled in other areas. The data from other locations is based on the number of cancer patients who have voluntarily sought medical attention. In Fukushima, however, 70 percent of all the children living in the prefecture underwent medical testing. Such widespread screening can produce a “screening effect,” which means that the incidence rises because even cancers that produce no symptoms or minute cancers can be detected.

The results of the first round of surveys could be explained by the screening effect. But the second round of surveys found 59 new cases, or suspected cases, of cancer. Some believe the screening effect cannot account for these results because, of the 59 cases, 54 were deemed problem-free in the first round. This suggests that cases of cancer which require surgery developed in as short a period as two years. When the committee met earlier this month, one member said that the rate in which the cancer is growing appears different from that of ordinary cases.

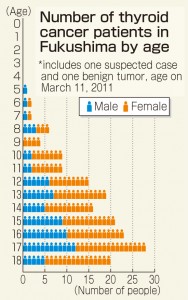

Attention must also be paid to the male-female ration. In Japan, the incidence of spontaneous thyroid cancer in children is four to five times higher in females than in males. But in Fukushima, of the 175 people who are suspected of having cancer, including one with a benign tumor, 111 are female and 64 are male. Thus, the number of females is 1.7 times that of males, resulting in a narrower difference between the genders. A report compiled in Belarus after the 1986 accident at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant in the former Soviet Union states that the difference between the genders was less than twofold in cases of thyroid cancers suspected of having been caused by the effects of radiation exposure. This leads some medical experts to suspect that cases of cancer in Fukushima were induced by the effects of radiation exposure in the wake of the nuclear accident.

Difference in age distribution between Fukushima and Chernobyl

The official view of the Fukushima committee is that the effects of exposure to radiation is likely not the cause of the greater incidence of cancer. One reason they are inclined to this opinion is that the age distribution for cases of thyroid cancer in Fukushima differs from such cases following the nuclear accident at Chernobyl.

Over a dozen years after that accident, British researchers conducted a survey around Chernobyl, in Belarus, on children with thyroid cancer who were 15 or younger at the time of the disaster. It was found that one in four of this group were 2 or younger when the accident occurred. In Fukushima, on the other hand, 90 percent of those diagnosed with thyroid cancer, or suspected of having thyroid cancer, were 10 or older at the time of the Fukushima accident. Among these children, only one can be included in the age group of 5 or younger, which is thought to be the age range most heavily influenced by exposure to radiation.

These two statistics, though, are significantly different in their periods of observation, so they cannot be readily compared. There is the possibility that the age distribution of Fukushima cases may come to look similar to that of Chernobyl in the future as the investigation continues.

Difficulty in estimating radiation doses

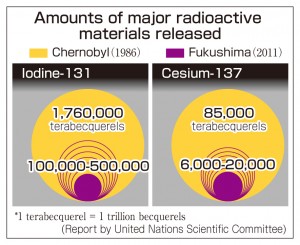

The United Nations Science Committee has estimated that the amounts of radioactive iodine (iodine-131) and cesium (cesium-137) released into the atmosphere in Fukushima were about 10 and 20 percent, respectively, of those of the Chernobyl accident. This is another reason why the Fukushima committee believes that the thyroid cancer cases in Fukushima are likely not linked to the accident.

A group of researchers at Fukushima Medical University analyzed the relationship between the estimated external exposure dose and cancer for each of approximately 120,000 people who were covered both in the prefecture’s basic survey, a questionnaire on how they behaved at the time of the accident, and thyroid gland tests. The group announced in an academic journal this month that no significant relationship was found.

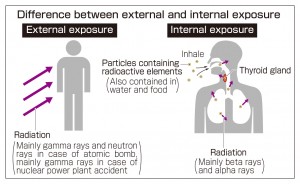

Some researchers point out that internal exposure doses should also be taken into account. Internal exposure is caused by taking radioactive elements into the body via particles in contaminated air, food, or water. As for the thyroid, most of the problems are caused by iodine-131. Megu Otaki, a professor emeritus of biometrics at Hiroshima University, said, “Internal exposure through particles can have extraordinary effects on internal organs. Effects on the thyroid should not be assessed based only on the estimated radiation dose of external exposure.”

Yet there is no precise test data that can provide clear evidence of internal exposure. The Ministry of the Environment is now trying to review the data, but the half-life of iodine-131 is eight days, which makes it difficult to find traces of this substance. It is therefore very difficult to assess the internal exposure doses of the people of Fukushima.

Gene analysis continues

A group of researchers led by Norisato Mitsutake, an associate professor at Nagasaki University, released a paper in 2015 which provided a gene mutation analysis of 68 child thyroid cancer cases in Fukushima. The paper said that 63 percent of these cases were BRAF mutations, which are often found in adults. On the other hand, radiation-induced mutations were most often seen in Chernobyl. The paper concluded that different cancer-forming mechanisms were at work in these two areas.

However, most of the Fukushima patients are 10 or older, whereas most in Chernobyl were younger than 10. Considering the difference in gene mutation patterns according to age, it is not necessarily appropriate to compare this data. Hokuto Hoshi, leader of the committee and vice president of the Fukushima Prefectural Medical Association, said, “If there are gene mutations that can be regarded as solid evidence of radiation exposure, we want to examine them.”

Various views on scale of health surveys

As the surveys pursued by the prefectural government find more children with thyroid cancer, some pediatricians in Fukushima are beginning to voice the view that such surveys should be scaled back because the results are making examineeds feel more anxious. But five and a half years after the accident at Chernobyl, the number of children with thyroid cancer has begun to rise. If the surveys in Fukushima were to be scaled back now, this could compromise the reliability of the results and hinder the early detection of cancer.

Still, a group of pediatricians in the prefecture contends that the scale of the surveys should be reduced. The group has submitted a request to the prefectural government calling for a review of the healthy surveys. The request stated that seeking out slow-growing and good-prognosis thyroid cancer brings few benefits. The mere fact that many cases of cancer have been found will cause the whole population of Fukushima to suffer from harmful rumors, it said. The pediatricians argue that the current surveys are excessive.

Nevertheless, the survey committee met this month in the city of Fukushima and most of the members agreed that the survey system should be continued in its present form. One member, Kazuo Shimizu, a professor emeritus at Nippon Medical School in Tokyo, took part in the support provided to cancer patients after the Chernobyl accident. He said, “The surveys have been conducted on an unprecedented scale in the history of medicine. Considering that the effects of radiation may come to be revealed, we should maintain the surveys at their current scale for at least the next 10 years.”

Even now, participation rates in the surveys are significantly different according to age group. In the second round surveys conducted in fiscal 2014 and 2015, more than 80 percent of those in the age brackets of 8 to 12 and 13 to 17 were examined, compared with only 25.5 percent of those between 18 and 22, many of whom live out of the prefecture. If adequate data is not accumulated, this will compromise the reliability of the surveys. So the participation rates need to be improved.

The third round of surveys will begin in fiscal 2016. On the interview sheets prepared by the prefectural government, a check box was newly added in order to ask if people do not agree to be examined. Some members of the committee said that this could reduce the participation rate. The prefectural government commented that it has not changed its stance of recommending that participate in the surveys, but that their free will should be respected.

Interview with Dr. Nobuo Takeichi: “We should not rush to a conclusion.”

Nobuo Takeichi, 72, is a physician specializing in the thyroid gland and has a clinic in Minami Ward, Hiroshima. Dr. Takeichi has been involved in clinical examinations of A-bomb survivors and children who suffered from the Chernobyl accident. The Chugoku Shimbun interviewed Dr. Takeichi about issues that should be addressed in connection with the many cases of thyroid cancer that have been found in children in Fukushima.

Even in areas with no radioactive contamination, some people develop thyroid cancer between the ages of 16 and 18, with the peak at around age 40. It is too early to determine whether or not the cases of thyroid cancer now found in Fukushima have been induced by radiation exposure. We should not rush to a conclusion.

My impression is that the situation in Fukushima is different from that of Chernobyl. Five years after the Chernobyl accident, I began examining the thyroid glands of almost 1,000 children in Ukraine and other locations and I found that the more contaminated the area was, the harder the children’s thyroids glands were. I have examined about 120 children from Fukushima at my clinic, but most of their thyroid glands were not hard.

To discuss whether or not the cases of thyroid cancer found in Fukushima have been caused by radiation, it is important to examine the amount of radioactive iodine taken into the body and determine the internal exposure dose. Among the 300,000 people in Fukushima whose thyroid glands were examined, data on their internal exposure doses are available for only 1,000 people, which is far too small a number.

We must also put more focus on the differences between Fukushima and other areas that are not contaminated. The Ministry of the Environment surveyed a total of 4,500 people in Aomori, Yamanashi, and Nagasaki prefectures in 2012. But the number is too small and apparently no follow-up surveys have been conducted. At least 10,000 people in each area should be observed.

Through health checkups for A-bomb survivors, Hiroshima has accumulated knowledge on how to examine thyroid glands. How can we support Fukushima? It would be ideal if 10,000 children between the ages of 5 and 10 are examined every two years for a duration of 10 years as part of health checkups conducted in local schools.

The youngest children covered by Fukushima Prefecture’s thyroid gland surveys were born within a year of the accident. These children can be affected by residual radiation. They should be compared with those born in the prefecture in the second year, and after, following the accident.

Citizens monitor radiation levels to ensure safety

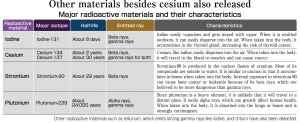

While cesium is generally the focus of the radioactive materials released in the accident at the nuclear power plant in Fukushima, other radioactive materials, including iodine and small amounts of strontium and tritium, were released, too. To what degree are radioactive substances found in food and drinking water? To ensure their own safety, citizens are actively monitoring these radiation levels.

On a fine morning in early September, a fishing boat carrying 10 members of the Iwaki Radiation Measuring Center, Tarachine, an NPO, left Hisanohama Port in Iwaki, Fukushima Prefecture. After an hour and a half, the boat reached an offshore area 1.5 kilometers southeast of the power plant and collected seawater for analysis. This is the fourth in a series of surveys pursued since last year.

With the boat swaying from side to side, the members of the NPO had a difficult time collecting the seawater. Changing positions as they worked, they collected a total of 200 liters. They also caught two flatfish and two greenlings.

“It is harder to grasp the conditions of the ocean compared to the land. Our aim is to monitor the changes the ocean is going through after the accident from the perspective of ordinary citizens,” said Kaori Suzuki, the head of the NPO. The seawater they collected will be brought to the organization’s office in Iwaki for analysis. In the last survey conducted in June, a tiny amount of tritium was detected. The survey results are posted on the NPO’s website.

Surprisingly, they have a beta-ray measurement laboratory in their office, which was installed in April 2014 at a cost of 35 million yen. Their measuring instruments include a high sensitivity liquid scintillation counter.

Holding a bowl that contained powdered sardine, which was brought in for analysis, Hikaru Amano, 67, said, “People don’t want any time lost in determining the truth. We need to respond to their expectations.” Dr. Amano is the technical manager of the laboratory. A paper describing the Tarachine Method, a swift and accurate method of measurement developed at the laboratory, has appeared in an English-language science journal.

Measuring radioactive materials such as strontium or tritium, which emit beta rays, takes time and is challenging from a technical standpoint. According to the NPO, many civic groups around the country are measuring gamma rays, but Tarachine is the only group that can measure beta rays.

Tarachine is a Japanese poetic epithet used in a waka poem in association with the word mother. The group was formed mainly by housewives living in the city of Iwaki eight months after the nuclear accident. Ms. Suzuki, a mother of two, used to teach yoga while raising her children. The accident at the nuclear plant changed everything.

The NPO has conducted thyroid gland tests and whole body radiation exposure tests, as well as measuring cesium in various items brought in by citizens, including a filter from a vacuum cleaner. The group also buys organic vegetables from Hiroshima every week. Everything they do is intended to keep the local children safe. The members of the group have begun to feel that finding gamma rays alone is insufficient in grasping the presence of radiation.

When they requested a national organization to measure beta rays, they were told that this would cost 200,000 yen. “We couldn’t afford to pay such a large sum, so we racked our brains to figure out how we could meet this challenge.” They were able to obtain the needed funds through private donations and aid from citizens’ groups. Through various contacts, they asked for support from Dr. Amano, who is an expert in analyzing radioactive materials. Requests for analysis now come from overseas, too, including Canada. The charge is only 3,000 yen.

“Are the food and water and soil safe? We want to know the truth. This is the feeling we all share, whether we’re part of the fishing industry or another industry,” said Ms. Suzuki.

Keywords

Tritium

Tritium, also known as hydrogen-3, is a radioactive isotope of hydrogen. Its half-life is about 12 years. It exists in nature but is also produced through nuclear fission in reactors. Because international regulations permit tritium to be released into the ocean when it is below a set value, nuclear power plants discharge this substance into the ocean after dilution. When tritium is mixed with water, it is hard to separate them. Contaminated water at the Fukushima No. 1 (Daiichi) nuclear power plant has a large amount of tritium that cannot be removed using the multi-nuclide removal facility (Advanced Liquid Processing System).

(Originally published on September 23, 2016)

by Yumi Kanazaki and Yota Baba, Staff Writers

Five and a half years have passed since the accident at the Fukushima No. 1 (Daiichi) nuclear power plant, which spewed radioactive substances such as iodine and cesium over broad swaths of land and into the ocean. Health surveys carried out by the Fukushima prefectural government have found that 174 children either have or are suspected of having thyroid cancer. Studies on the natural surroundings have also been conducted. Have the effects of exposure to low-level radiation already manifested? Or will they show up in time? Scientific approaches are seeking to reveal the truth.

Differing views on incidence of thyroid cancer in children

The health surveys carried out by the Fukushima prefectural government are aimed at discerning the health effects of the nuclear power plant accident. In 2011, the committee overseeing the surveys began performing ultrasound examinations on the thyroid glands of children who were 18 or younger at the time of the nuclear disaster. About 300,000 people, or 70 percent of this population, underwent the tests. So far, 135 are confirmed to have cancer that is malignant, and 39 are suspected of having cancer.

Some researchers regard this incidence as “plainly high,” considering the normal incidence of children’s thyroid cancer, an estimate based on statistics from different areas of the country which amounts to only a handful per million. The interim report compiled by the committee in March 2016 states that the incidence discovered is dozens of times higher when compared to other statistics for cancer.

On the other hand, many researchers support the view that the Fukushima data cannot be compared to cancer statistics compiled in other areas. The data from other locations is based on the number of cancer patients who have voluntarily sought medical attention. In Fukushima, however, 70 percent of all the children living in the prefecture underwent medical testing. Such widespread screening can produce a “screening effect,” which means that the incidence rises because even cancers that produce no symptoms or minute cancers can be detected.

The results of the first round of surveys could be explained by the screening effect. But the second round of surveys found 59 new cases, or suspected cases, of cancer. Some believe the screening effect cannot account for these results because, of the 59 cases, 54 were deemed problem-free in the first round. This suggests that cases of cancer which require surgery developed in as short a period as two years. When the committee met earlier this month, one member said that the rate in which the cancer is growing appears different from that of ordinary cases.

Attention must also be paid to the male-female ration. In Japan, the incidence of spontaneous thyroid cancer in children is four to five times higher in females than in males. But in Fukushima, of the 175 people who are suspected of having cancer, including one with a benign tumor, 111 are female and 64 are male. Thus, the number of females is 1.7 times that of males, resulting in a narrower difference between the genders. A report compiled in Belarus after the 1986 accident at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant in the former Soviet Union states that the difference between the genders was less than twofold in cases of thyroid cancers suspected of having been caused by the effects of radiation exposure. This leads some medical experts to suspect that cases of cancer in Fukushima were induced by the effects of radiation exposure in the wake of the nuclear accident.

Difference in age distribution between Fukushima and Chernobyl

The official view of the Fukushima committee is that the effects of exposure to radiation is likely not the cause of the greater incidence of cancer. One reason they are inclined to this opinion is that the age distribution for cases of thyroid cancer in Fukushima differs from such cases following the nuclear accident at Chernobyl.

Over a dozen years after that accident, British researchers conducted a survey around Chernobyl, in Belarus, on children with thyroid cancer who were 15 or younger at the time of the disaster. It was found that one in four of this group were 2 or younger when the accident occurred. In Fukushima, on the other hand, 90 percent of those diagnosed with thyroid cancer, or suspected of having thyroid cancer, were 10 or older at the time of the Fukushima accident. Among these children, only one can be included in the age group of 5 or younger, which is thought to be the age range most heavily influenced by exposure to radiation.

These two statistics, though, are significantly different in their periods of observation, so they cannot be readily compared. There is the possibility that the age distribution of Fukushima cases may come to look similar to that of Chernobyl in the future as the investigation continues.

Difficulty in estimating radiation doses

The United Nations Science Committee has estimated that the amounts of radioactive iodine (iodine-131) and cesium (cesium-137) released into the atmosphere in Fukushima were about 10 and 20 percent, respectively, of those of the Chernobyl accident. This is another reason why the Fukushima committee believes that the thyroid cancer cases in Fukushima are likely not linked to the accident.

A group of researchers at Fukushima Medical University analyzed the relationship between the estimated external exposure dose and cancer for each of approximately 120,000 people who were covered both in the prefecture’s basic survey, a questionnaire on how they behaved at the time of the accident, and thyroid gland tests. The group announced in an academic journal this month that no significant relationship was found.

Some researchers point out that internal exposure doses should also be taken into account. Internal exposure is caused by taking radioactive elements into the body via particles in contaminated air, food, or water. As for the thyroid, most of the problems are caused by iodine-131. Megu Otaki, a professor emeritus of biometrics at Hiroshima University, said, “Internal exposure through particles can have extraordinary effects on internal organs. Effects on the thyroid should not be assessed based only on the estimated radiation dose of external exposure.”

Yet there is no precise test data that can provide clear evidence of internal exposure. The Ministry of the Environment is now trying to review the data, but the half-life of iodine-131 is eight days, which makes it difficult to find traces of this substance. It is therefore very difficult to assess the internal exposure doses of the people of Fukushima.

Gene analysis continues

A group of researchers led by Norisato Mitsutake, an associate professor at Nagasaki University, released a paper in 2015 which provided a gene mutation analysis of 68 child thyroid cancer cases in Fukushima. The paper said that 63 percent of these cases were BRAF mutations, which are often found in adults. On the other hand, radiation-induced mutations were most often seen in Chernobyl. The paper concluded that different cancer-forming mechanisms were at work in these two areas.

However, most of the Fukushima patients are 10 or older, whereas most in Chernobyl were younger than 10. Considering the difference in gene mutation patterns according to age, it is not necessarily appropriate to compare this data. Hokuto Hoshi, leader of the committee and vice president of the Fukushima Prefectural Medical Association, said, “If there are gene mutations that can be regarded as solid evidence of radiation exposure, we want to examine them.”

Various views on scale of health surveys

As the surveys pursued by the prefectural government find more children with thyroid cancer, some pediatricians in Fukushima are beginning to voice the view that such surveys should be scaled back because the results are making examineeds feel more anxious. But five and a half years after the accident at Chernobyl, the number of children with thyroid cancer has begun to rise. If the surveys in Fukushima were to be scaled back now, this could compromise the reliability of the results and hinder the early detection of cancer.

Still, a group of pediatricians in the prefecture contends that the scale of the surveys should be reduced. The group has submitted a request to the prefectural government calling for a review of the healthy surveys. The request stated that seeking out slow-growing and good-prognosis thyroid cancer brings few benefits. The mere fact that many cases of cancer have been found will cause the whole population of Fukushima to suffer from harmful rumors, it said. The pediatricians argue that the current surveys are excessive.

Nevertheless, the survey committee met this month in the city of Fukushima and most of the members agreed that the survey system should be continued in its present form. One member, Kazuo Shimizu, a professor emeritus at Nippon Medical School in Tokyo, took part in the support provided to cancer patients after the Chernobyl accident. He said, “The surveys have been conducted on an unprecedented scale in the history of medicine. Considering that the effects of radiation may come to be revealed, we should maintain the surveys at their current scale for at least the next 10 years.”

Even now, participation rates in the surveys are significantly different according to age group. In the second round surveys conducted in fiscal 2014 and 2015, more than 80 percent of those in the age brackets of 8 to 12 and 13 to 17 were examined, compared with only 25.5 percent of those between 18 and 22, many of whom live out of the prefecture. If adequate data is not accumulated, this will compromise the reliability of the surveys. So the participation rates need to be improved.

The third round of surveys will begin in fiscal 2016. On the interview sheets prepared by the prefectural government, a check box was newly added in order to ask if people do not agree to be examined. Some members of the committee said that this could reduce the participation rate. The prefectural government commented that it has not changed its stance of recommending that participate in the surveys, but that their free will should be respected.

Interview with Dr. Nobuo Takeichi: “We should not rush to a conclusion.”

Nobuo Takeichi, 72, is a physician specializing in the thyroid gland and has a clinic in Minami Ward, Hiroshima. Dr. Takeichi has been involved in clinical examinations of A-bomb survivors and children who suffered from the Chernobyl accident. The Chugoku Shimbun interviewed Dr. Takeichi about issues that should be addressed in connection with the many cases of thyroid cancer that have been found in children in Fukushima.

Even in areas with no radioactive contamination, some people develop thyroid cancer between the ages of 16 and 18, with the peak at around age 40. It is too early to determine whether or not the cases of thyroid cancer now found in Fukushima have been induced by radiation exposure. We should not rush to a conclusion.

My impression is that the situation in Fukushima is different from that of Chernobyl. Five years after the Chernobyl accident, I began examining the thyroid glands of almost 1,000 children in Ukraine and other locations and I found that the more contaminated the area was, the harder the children’s thyroids glands were. I have examined about 120 children from Fukushima at my clinic, but most of their thyroid glands were not hard.

To discuss whether or not the cases of thyroid cancer found in Fukushima have been caused by radiation, it is important to examine the amount of radioactive iodine taken into the body and determine the internal exposure dose. Among the 300,000 people in Fukushima whose thyroid glands were examined, data on their internal exposure doses are available for only 1,000 people, which is far too small a number.

We must also put more focus on the differences between Fukushima and other areas that are not contaminated. The Ministry of the Environment surveyed a total of 4,500 people in Aomori, Yamanashi, and Nagasaki prefectures in 2012. But the number is too small and apparently no follow-up surveys have been conducted. At least 10,000 people in each area should be observed.

Through health checkups for A-bomb survivors, Hiroshima has accumulated knowledge on how to examine thyroid glands. How can we support Fukushima? It would be ideal if 10,000 children between the ages of 5 and 10 are examined every two years for a duration of 10 years as part of health checkups conducted in local schools.

The youngest children covered by Fukushima Prefecture’s thyroid gland surveys were born within a year of the accident. These children can be affected by residual radiation. They should be compared with those born in the prefecture in the second year, and after, following the accident.

Citizens monitor radiation levels to ensure safety

While cesium is generally the focus of the radioactive materials released in the accident at the nuclear power plant in Fukushima, other radioactive materials, including iodine and small amounts of strontium and tritium, were released, too. To what degree are radioactive substances found in food and drinking water? To ensure their own safety, citizens are actively monitoring these radiation levels.

On a fine morning in early September, a fishing boat carrying 10 members of the Iwaki Radiation Measuring Center, Tarachine, an NPO, left Hisanohama Port in Iwaki, Fukushima Prefecture. After an hour and a half, the boat reached an offshore area 1.5 kilometers southeast of the power plant and collected seawater for analysis. This is the fourth in a series of surveys pursued since last year.

With the boat swaying from side to side, the members of the NPO had a difficult time collecting the seawater. Changing positions as they worked, they collected a total of 200 liters. They also caught two flatfish and two greenlings.

“It is harder to grasp the conditions of the ocean compared to the land. Our aim is to monitor the changes the ocean is going through after the accident from the perspective of ordinary citizens,” said Kaori Suzuki, the head of the NPO. The seawater they collected will be brought to the organization’s office in Iwaki for analysis. In the last survey conducted in June, a tiny amount of tritium was detected. The survey results are posted on the NPO’s website.

Surprisingly, they have a beta-ray measurement laboratory in their office, which was installed in April 2014 at a cost of 35 million yen. Their measuring instruments include a high sensitivity liquid scintillation counter.

Holding a bowl that contained powdered sardine, which was brought in for analysis, Hikaru Amano, 67, said, “People don’t want any time lost in determining the truth. We need to respond to their expectations.” Dr. Amano is the technical manager of the laboratory. A paper describing the Tarachine Method, a swift and accurate method of measurement developed at the laboratory, has appeared in an English-language science journal.

Measuring radioactive materials such as strontium or tritium, which emit beta rays, takes time and is challenging from a technical standpoint. According to the NPO, many civic groups around the country are measuring gamma rays, but Tarachine is the only group that can measure beta rays.

Tarachine is a Japanese poetic epithet used in a waka poem in association with the word mother. The group was formed mainly by housewives living in the city of Iwaki eight months after the nuclear accident. Ms. Suzuki, a mother of two, used to teach yoga while raising her children. The accident at the nuclear plant changed everything.

The NPO has conducted thyroid gland tests and whole body radiation exposure tests, as well as measuring cesium in various items brought in by citizens, including a filter from a vacuum cleaner. The group also buys organic vegetables from Hiroshima every week. Everything they do is intended to keep the local children safe. The members of the group have begun to feel that finding gamma rays alone is insufficient in grasping the presence of radiation.

When they requested a national organization to measure beta rays, they were told that this would cost 200,000 yen. “We couldn’t afford to pay such a large sum, so we racked our brains to figure out how we could meet this challenge.” They were able to obtain the needed funds through private donations and aid from citizens’ groups. Through various contacts, they asked for support from Dr. Amano, who is an expert in analyzing radioactive materials. Requests for analysis now come from overseas, too, including Canada. The charge is only 3,000 yen.

“Are the food and water and soil safe? We want to know the truth. This is the feeling we all share, whether we’re part of the fishing industry or another industry,” said Ms. Suzuki.

Keywords

Tritium

Tritium, also known as hydrogen-3, is a radioactive isotope of hydrogen. Its half-life is about 12 years. It exists in nature but is also produced through nuclear fission in reactors. Because international regulations permit tritium to be released into the ocean when it is below a set value, nuclear power plants discharge this substance into the ocean after dilution. When tritium is mixed with water, it is hard to separate them. Contaminated water at the Fukushima No. 1 (Daiichi) nuclear power plant has a large amount of tritium that cannot be removed using the multi-nuclide removal facility (Advanced Liquid Processing System).

(Originally published on September 23, 2016)