Survivors’ Stories: Etsuheiji Osada, 89, Higashi Ward, Hiroshima

Feb. 6, 2017

Photographs from that time bring back the horror of the atomic bombing

by Yuji Yamamoto, Staff Writer

Etsuheiji Osada, 89, still has photographs that show the charred ruins of the city center and a mother who suffered burns holding her baby to her breast. These were consequences wrought by the atomic bombing of Hiroshima. Around 1960, Mr. Osada, who became a photographer after his experience of the bombing, was looking through some negatives at work and came across some images that brought back memories of that day. Unsettled by these images, he nevertheless felt that they should be developed and printed in order to help convey the horror of the A-bomb attack. And so he has kept these photos ever since.

As a boy, he struggled with poor health, suffering from a lung ailment. After graduating from school, he went to work helping his father, Shozo, retouch photographs at home. When his father expressed concern about air raids on the city, Mr. Osada moved from Dote-cho (now part of Minami Ward) to the suburbs of Akebono-cho (now part of Higashi Ward) in June 1945.

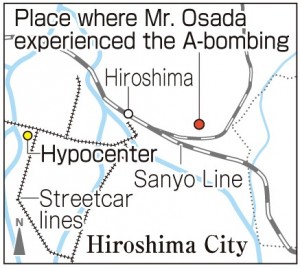

Mr. Osada has vivid memories of August 6, 1945. He was 17 years old at the time and was having breakfast with his parents at home, about 3 kilometers from the hypocenter. They heard a neighbor shout, “There’s a B-29 bomber and it dropped something!” He headed upstairs to look and as he opened a door, there was a flash of light. The flash was so bright, like a flash of magnesium in front of his face.

Suddenly, he felt as if he were floating in the air. He fell into his parents, who were going up the stairs and were also blown into the air by the blast. Two or three spots on his head were pierced with fragments of glass, but he felt no pain.

He wondered what the plane had dropped. When he went out of the house, he heard people crying out and screaming. It was dark under a massive cloud, rising into the sky, and houses around him were collapsing to the ground with thunderous noise. People were fleeing from the area, their faces black from soot, their hair flopping to their foreheads. The burnt skin of some was dangling from their bodies and one man’s chest had been pierced by a post. This bomb was too powerful to be an ordinary bomb, Mr. Osada thought. His sister Michiko, who was a year older, had left home to go to the Hiroshima District Monopoly Bureau, located in Minami-machi (now part of Minami Ward), where she was working. He was worried about her. He put up mosquito netting in the field in front of his house and spent the night there.

He left home the next morning and was shocked by what he saw in the city center. There were charred bodies inside a streetcar, and badly burned victims, nearly unrecognizable, in front of the Chugoku Shimbun and Fukuya Department Store. Water pipes had burst around them, cutting off their escape. They were begging for water. It was a shocking sight. When he returned home, at around noon, his sister was there. He was so glad that everyone in his family was safe.

But his father’s photo studio in the city center had been obliterated and it was impossible to take on any new work. With their house also destroyed, they no longer had a place to live. In September, Mr. Osada and his family moved to Iki Island in Nagasaki Prefecture, his father’s hometown. They were received warmly by relatives and, for the next five years, lived a life of farming and fishing.

Mr. Osada overcame his lung ailment and he began to pine for life in the city. He returned to Hiroshima with his family and learned more about photography. In 1961, around the time he discovered the negatives at the company he was working for, he married Yoshiko, who is now 78.

The City of Hiroshima asked him to create a collection of slides that could convey the catastrophic conditions of the atomic bombing. He thought he had been able to keep his A-bomb memories in the back of his mind, but as he worked on this project, they suddenly came flooding back. He said, “During the war, we had gotten so used to the air raid attacks by the bombers and the widespread damage they caused.”

More than 50 years have passed since that project, and Mr. Osada is now retired and age has taken a toll on his memory. “I could die at any time,” he said uncertainly. But he has carefully maintained these photographs among items that reflect his A-bomb experience. Voicing his strong appeal for nuclear abolition, he said, “Even people today who don’t know the horror of nuclear weapons can understand when they see the photographs. If a nuclear weapon is used again, the whole human race could perish.”

Teenagers’ Impressions

Surprised to learn that some people wanted to fight

I was surprised to learn that some people wanted to go to the front lines of the war to fight. After all, they might die there without seeing their family members again. Ms. Osada said he wanted to be a soldier, too, but he couldn’t and instead worked at the photo studio as he watched soldiers heading off to war. Perhaps he felt frustrated, but he worked diligently until he finally retired. (Yui Morimoto, 14)

Nuclear weapons must never be used

When the atomic bomb exploded, Mr. Osada was blown through the air from upstairs in his house. This was a distance of 3 kilometers from the hypocenter, so the blast must have been tremendous. Today, nuclear weapons are even more powerful, more destructive, and if they’re used even once, there would be a lot more damage than what happened in Hiroshima. We have to prevent nuclear weapons from ever being used again. (Hiromi Ueoka, 16)

If countries don’t compromise, a peaceful world can’t be realized

When one country produces nuclear weapons, other countries want to produce them, too, to maintain their rivalry. If nuclear weapons are used, the world could be destroyed. As Mr. Osada said, we don’t have to try to be the strongest all the time. If countries only compete to see who’s strongest, and don’t compromise, nuclear weapons will continue to be produced and we’ll never be able to live in a safe and peaceful world. (Terumi Okada, 16)

(Originally published on February 6, 2017)

by Yuji Yamamoto, Staff Writer

Etsuheiji Osada, 89, still has photographs that show the charred ruins of the city center and a mother who suffered burns holding her baby to her breast. These were consequences wrought by the atomic bombing of Hiroshima. Around 1960, Mr. Osada, who became a photographer after his experience of the bombing, was looking through some negatives at work and came across some images that brought back memories of that day. Unsettled by these images, he nevertheless felt that they should be developed and printed in order to help convey the horror of the A-bomb attack. And so he has kept these photos ever since.

As a boy, he struggled with poor health, suffering from a lung ailment. After graduating from school, he went to work helping his father, Shozo, retouch photographs at home. When his father expressed concern about air raids on the city, Mr. Osada moved from Dote-cho (now part of Minami Ward) to the suburbs of Akebono-cho (now part of Higashi Ward) in June 1945.

Mr. Osada has vivid memories of August 6, 1945. He was 17 years old at the time and was having breakfast with his parents at home, about 3 kilometers from the hypocenter. They heard a neighbor shout, “There’s a B-29 bomber and it dropped something!” He headed upstairs to look and as he opened a door, there was a flash of light. The flash was so bright, like a flash of magnesium in front of his face.

Suddenly, he felt as if he were floating in the air. He fell into his parents, who were going up the stairs and were also blown into the air by the blast. Two or three spots on his head were pierced with fragments of glass, but he felt no pain.

He wondered what the plane had dropped. When he went out of the house, he heard people crying out and screaming. It was dark under a massive cloud, rising into the sky, and houses around him were collapsing to the ground with thunderous noise. People were fleeing from the area, their faces black from soot, their hair flopping to their foreheads. The burnt skin of some was dangling from their bodies and one man’s chest had been pierced by a post. This bomb was too powerful to be an ordinary bomb, Mr. Osada thought. His sister Michiko, who was a year older, had left home to go to the Hiroshima District Monopoly Bureau, located in Minami-machi (now part of Minami Ward), where she was working. He was worried about her. He put up mosquito netting in the field in front of his house and spent the night there.

He left home the next morning and was shocked by what he saw in the city center. There were charred bodies inside a streetcar, and badly burned victims, nearly unrecognizable, in front of the Chugoku Shimbun and Fukuya Department Store. Water pipes had burst around them, cutting off their escape. They were begging for water. It was a shocking sight. When he returned home, at around noon, his sister was there. He was so glad that everyone in his family was safe.

But his father’s photo studio in the city center had been obliterated and it was impossible to take on any new work. With their house also destroyed, they no longer had a place to live. In September, Mr. Osada and his family moved to Iki Island in Nagasaki Prefecture, his father’s hometown. They were received warmly by relatives and, for the next five years, lived a life of farming and fishing.

Mr. Osada overcame his lung ailment and he began to pine for life in the city. He returned to Hiroshima with his family and learned more about photography. In 1961, around the time he discovered the negatives at the company he was working for, he married Yoshiko, who is now 78.

The City of Hiroshima asked him to create a collection of slides that could convey the catastrophic conditions of the atomic bombing. He thought he had been able to keep his A-bomb memories in the back of his mind, but as he worked on this project, they suddenly came flooding back. He said, “During the war, we had gotten so used to the air raid attacks by the bombers and the widespread damage they caused.”

More than 50 years have passed since that project, and Mr. Osada is now retired and age has taken a toll on his memory. “I could die at any time,” he said uncertainly. But he has carefully maintained these photographs among items that reflect his A-bomb experience. Voicing his strong appeal for nuclear abolition, he said, “Even people today who don’t know the horror of nuclear weapons can understand when they see the photographs. If a nuclear weapon is used again, the whole human race could perish.”

Teenagers’ Impressions

Surprised to learn that some people wanted to fight

I was surprised to learn that some people wanted to go to the front lines of the war to fight. After all, they might die there without seeing their family members again. Ms. Osada said he wanted to be a soldier, too, but he couldn’t and instead worked at the photo studio as he watched soldiers heading off to war. Perhaps he felt frustrated, but he worked diligently until he finally retired. (Yui Morimoto, 14)

Nuclear weapons must never be used

When the atomic bomb exploded, Mr. Osada was blown through the air from upstairs in his house. This was a distance of 3 kilometers from the hypocenter, so the blast must have been tremendous. Today, nuclear weapons are even more powerful, more destructive, and if they’re used even once, there would be a lot more damage than what happened in Hiroshima. We have to prevent nuclear weapons from ever being used again. (Hiromi Ueoka, 16)

If countries don’t compromise, a peaceful world can’t be realized

When one country produces nuclear weapons, other countries want to produce them, too, to maintain their rivalry. If nuclear weapons are used, the world could be destroyed. As Mr. Osada said, we don’t have to try to be the strongest all the time. If countries only compete to see who’s strongest, and don’t compromise, nuclear weapons will continue to be produced and we’ll never be able to live in a safe and peaceful world. (Terumi Okada, 16)

(Originally published on February 6, 2017)