Survivors’ Stories: Mieko Yoshida, 84, Fuchu, Hiroshima Prefecture

Jan. 9, 2017

Unable to fulfill “last requests,” erects a monument in remembrance

by Rie Nii, Staff Writer

Mieko Yoshida (née Namba), now 84, was left the “last requests” of many people at Fuchu National School (now Fuchu Elementary School, located in Fuchu), which served as a temporary aid station after the atomic bombing. People she did not know urged her to convey messages like “Tell Hiroko that I’m here” and “Tell Ichiro that I was taking care of my family at home and I died.” But she was unable to fulfill these requests and felt remorse.

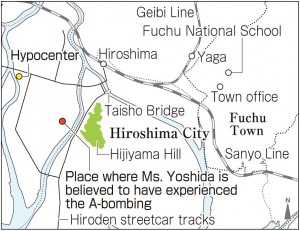

At the time of the atomic bombing, Ms. Yoshida was 12 years old, a first-year student at Fuchu National School and the president of the student council. On the morning of August 6, 1945, she traveled into the city of Hiroshima to help tear down buildings to create a fire lane. She was shown into an office in a building about 1.5 kilometers from the hypocenter that was located in Tsurumi-cho or Takara-machi (both are now part of Naka Ward) by a member of the Volunteer Citizens’ Corps. When she began to introduce herself, there was a great boom and the building began to collapse. She instinctively dove under a desk and was able to escape serious injury.

Fleeing the area, she headed for Hijiyama Hill and arrived at Tamon-in Temple. She tried to cross over the hill and return to her home, but the descending path was blocked by tree branches and she was unsure which way to go. She had no choice but to retreat to the road along the streetcar tracks on the west side of the hill.

A military truck happened to pass by, and Ms. Yoshida was quickly hauled into the truck bed. She asked where the truck was going, and hearing it was headed to Miiri (now part of Asakita Ward), she jumped off in haste.

Ms. Yoshida crossed Taisho Bridge, walked through the underground tunnel from Ozu-machi (now part of Minami Ward), stopped by her school, and finally arrived home. Her mother, Masami, came home from her place of work, the machinery department of the Japan National Railway, located east of Hiroshima Station. Her brother, Kaoru, who was three years older and a third-year student at Hiroshima Prefectural Hiroshima Commercial School (now Hiroshima Prefectural Hiroshima Commercial High School), was in front of Yaga Station on his way home from the Hiroshima plant of the Japan Steel Works (located in Nishikaniya-cho, now part of Minami Ward). This was his work site as a mobilized student and he had been on the night shift. He made it home safely, too.

However, Ms. Yoshida was unable to locate her sister, Masae, who was five years older and worked in the communications department at Hiroshima Station. With her brother, she went out in search of her sister. When they reached the vicinity of the East Drill Ground (now part of Higashi Ward), an old man with a black face asked if she was Mieko Namba. She looked at him closely and realized that he was a man named Mr. Yokota, a neighbor. It seemed Mr. Yokota could not move on his own. After they were able to confirm, at Hiroshima Station, that her sister had taken refuge in an air-raid shelter, they returned to their home for a cart and used it to carry Mr. Yokota back with them.

Around midnight, her mother’s cousin arrived from Showa-machi (now part of Naka Ward). He said that his wife had been trapped under a building and had burned to death. Early on the morning of August 7, she went to Show-machi and helped cremate the half-burned body.

At a school that served as a temporary aid station, Ms. Yoshida helped carry people to the auditorium on a stretcher, when they were unable to walk, and led people who were more mobile to classrooms on the second floor. Inside the classrooms, she and her classmates wrote people’s names and addresses on the blackboards. “Our handwriting was sloppy, but we wrote their names so family members who were searching for their loved ones could readily find them,” she explained.

Children also pitched in. They made straw by cutting down dried wheat and they helped carry bodies on large two-wheel carts. Mr. Yoshida recalled, “The school was like a ‘battlefield’ until around the middle of August.”

Some people at the school left behind a “last request” for Ms. Yoshida before they passed away. “I told them that I would help them,” Ms. Yoshida said, “but I’ve been unable to carry out their requests. I lied to them.” In 1985, she decided to erect a monument to mark the 40th anniversary of the atomic bombing. After the A-bomb attack, there was a pit in front of the town office where bodies were cremated. She planned to place the monument there.

She launched a fundraising effort in November 1984, to raise 3 million yen to cover the costs, but this campaign did not proceed as she hoped. However, in the spring of 1985, after she made a pilgrimage to 88 temples in Shikoku, contributions now came and, in the end, she was able to raise 5.8 million yen. She said she was pleased that the monument could be created and imbued with the spirits of the victims she had known.

Ms. Yoshida was a town councilor for 40 years, until 2012. “I hope that young people will live in harmony with one another and become the kind of person who listens carefully to what others say,” she said. “Relationships between nations and relationships between people are one and the same.”

Teenagers’ Impressions

Finding value even in hardships

There was a lot of chaos during and after the war. But Ms. Yoshida accepted her hardships as an important part of her life by saying that she would only feel sorry for herself if she didn’t think positively about the past. I was really impressed by her attitude. From now on, even when I have hard times, I want to see value in these experiences and link them to my life. (Akane Sato, 14)

Starting with what I can do

Many people at the school made “final requests” to Ms. Yoshida and she had no choice but to say she would carry them out. She was unable to do it, though, and she blamed herself. This is why she wanted to erect the monument for these people who had passed away and live her life as positively as she could. I want to do what I can, too, like listening to the experiences of the A-bomb survivors and relating these stories to younger generations. (Hinako Okada, 15)

Necessary to discern the truth

When Ms. Yoshida’s mother heard Emperor Hirohito’s broadcast announcing Japan’s surrender and explained to neighbors who were unable to hear it that Japan had lost the war, they accused her of lying. With this story, Ms. Yoshida was able to convey how fervently Japanese people of that time believed that Japan would win the war. There are no strict controls on free speech in modern Japan, but we need the capacity to distinguish what is true from what is false in the information that we hear. (Shino Taniguchi, 18)

(Originally published on January 9, 2017)

by Rie Nii, Staff Writer

Mieko Yoshida (née Namba), now 84, was left the “last requests” of many people at Fuchu National School (now Fuchu Elementary School, located in Fuchu), which served as a temporary aid station after the atomic bombing. People she did not know urged her to convey messages like “Tell Hiroko that I’m here” and “Tell Ichiro that I was taking care of my family at home and I died.” But she was unable to fulfill these requests and felt remorse.

At the time of the atomic bombing, Ms. Yoshida was 12 years old, a first-year student at Fuchu National School and the president of the student council. On the morning of August 6, 1945, she traveled into the city of Hiroshima to help tear down buildings to create a fire lane. She was shown into an office in a building about 1.5 kilometers from the hypocenter that was located in Tsurumi-cho or Takara-machi (both are now part of Naka Ward) by a member of the Volunteer Citizens’ Corps. When she began to introduce herself, there was a great boom and the building began to collapse. She instinctively dove under a desk and was able to escape serious injury.

Fleeing the area, she headed for Hijiyama Hill and arrived at Tamon-in Temple. She tried to cross over the hill and return to her home, but the descending path was blocked by tree branches and she was unsure which way to go. She had no choice but to retreat to the road along the streetcar tracks on the west side of the hill.

A military truck happened to pass by, and Ms. Yoshida was quickly hauled into the truck bed. She asked where the truck was going, and hearing it was headed to Miiri (now part of Asakita Ward), she jumped off in haste.

Ms. Yoshida crossed Taisho Bridge, walked through the underground tunnel from Ozu-machi (now part of Minami Ward), stopped by her school, and finally arrived home. Her mother, Masami, came home from her place of work, the machinery department of the Japan National Railway, located east of Hiroshima Station. Her brother, Kaoru, who was three years older and a third-year student at Hiroshima Prefectural Hiroshima Commercial School (now Hiroshima Prefectural Hiroshima Commercial High School), was in front of Yaga Station on his way home from the Hiroshima plant of the Japan Steel Works (located in Nishikaniya-cho, now part of Minami Ward). This was his work site as a mobilized student and he had been on the night shift. He made it home safely, too.

However, Ms. Yoshida was unable to locate her sister, Masae, who was five years older and worked in the communications department at Hiroshima Station. With her brother, she went out in search of her sister. When they reached the vicinity of the East Drill Ground (now part of Higashi Ward), an old man with a black face asked if she was Mieko Namba. She looked at him closely and realized that he was a man named Mr. Yokota, a neighbor. It seemed Mr. Yokota could not move on his own. After they were able to confirm, at Hiroshima Station, that her sister had taken refuge in an air-raid shelter, they returned to their home for a cart and used it to carry Mr. Yokota back with them.

Around midnight, her mother’s cousin arrived from Showa-machi (now part of Naka Ward). He said that his wife had been trapped under a building and had burned to death. Early on the morning of August 7, she went to Show-machi and helped cremate the half-burned body.

At a school that served as a temporary aid station, Ms. Yoshida helped carry people to the auditorium on a stretcher, when they were unable to walk, and led people who were more mobile to classrooms on the second floor. Inside the classrooms, she and her classmates wrote people’s names and addresses on the blackboards. “Our handwriting was sloppy, but we wrote their names so family members who were searching for their loved ones could readily find them,” she explained.

Children also pitched in. They made straw by cutting down dried wheat and they helped carry bodies on large two-wheel carts. Mr. Yoshida recalled, “The school was like a ‘battlefield’ until around the middle of August.”

Some people at the school left behind a “last request” for Ms. Yoshida before they passed away. “I told them that I would help them,” Ms. Yoshida said, “but I’ve been unable to carry out their requests. I lied to them.” In 1985, she decided to erect a monument to mark the 40th anniversary of the atomic bombing. After the A-bomb attack, there was a pit in front of the town office where bodies were cremated. She planned to place the monument there.

She launched a fundraising effort in November 1984, to raise 3 million yen to cover the costs, but this campaign did not proceed as she hoped. However, in the spring of 1985, after she made a pilgrimage to 88 temples in Shikoku, contributions now came and, in the end, she was able to raise 5.8 million yen. She said she was pleased that the monument could be created and imbued with the spirits of the victims she had known.

Ms. Yoshida was a town councilor for 40 years, until 2012. “I hope that young people will live in harmony with one another and become the kind of person who listens carefully to what others say,” she said. “Relationships between nations and relationships between people are one and the same.”

Teenagers’ Impressions

Finding value even in hardships

There was a lot of chaos during and after the war. But Ms. Yoshida accepted her hardships as an important part of her life by saying that she would only feel sorry for herself if she didn’t think positively about the past. I was really impressed by her attitude. From now on, even when I have hard times, I want to see value in these experiences and link them to my life. (Akane Sato, 14)

Starting with what I can do

Many people at the school made “final requests” to Ms. Yoshida and she had no choice but to say she would carry them out. She was unable to do it, though, and she blamed herself. This is why she wanted to erect the monument for these people who had passed away and live her life as positively as she could. I want to do what I can, too, like listening to the experiences of the A-bomb survivors and relating these stories to younger generations. (Hinako Okada, 15)

Necessary to discern the truth

When Ms. Yoshida’s mother heard Emperor Hirohito’s broadcast announcing Japan’s surrender and explained to neighbors who were unable to hear it that Japan had lost the war, they accused her of lying. With this story, Ms. Yoshida was able to convey how fervently Japanese people of that time believed that Japan would win the war. There are no strict controls on free speech in modern Japan, but we need the capacity to distinguish what is true from what is false in the information that we hear. (Shino Taniguchi, 18)

(Originally published on January 9, 2017)