Survivors’ Stories: Hiroshi Doi, 83, Nishi Ward, Hiroshima

Aug. 7, 2017

A-bombing turned the city into a picture of hell itself

by Miho Kuwajima, Staff Writer

Hiroshi Doi, 83, lost his elder and younger sisters in the atomic bombing. He worked as an engineer for 40 years at Shinko Industries, a local manufacturer in Minami Ward that makes marine pumps and turbines. He wrote down his memories of the horrific experience he endured at the age of 11, but he would not talk about it, not even to his family. This summer, 72 years after the atomic bombing, he began talking about his experience in public for the first time.

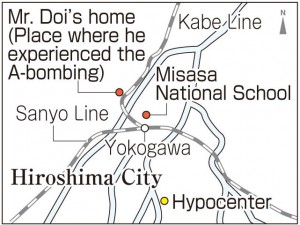

Back then, Mr. Doi was a sixth grader at Misasa National School (now Misasa Elementary School). On August 6, 1945, he was ill and at home in Mitaki-machi (now part of Nishi Ward), about 2.5 kilometers from the hypocenter. While resting in the living room after having breakfast, he was suddenly knocked to the floor by a tremendous blast, and plaster and boards came tumbling down.

Amid heavy dust, Mr. Doi rose fearfully and found that he had miraculously escaped injury, but his mother, right near him, was covered in blood. Fragments of shattered glass had been hurled through the air and were piercing the right side of her upper body, including her head, arm, and chest. He thought that the house had been hit directly by a bomb. He donned an air-raid hood and, with his younger brother and youngest sister, fled to the terraced fields of a hill behind his house. He watched as the school buildings of Misasa National School, which he attended, were engulfed in flames and collapsed.

Mr. Doi was the second of five siblings. He had an elder sister, two younger sisters, and a younger brother. His father, who had run an ironworks before the war, was drafted into the Japanese Navy as an engineer in December 1941 and was killed in battle on the Gilbert Islands in November 1943. Moreover, the atomic bombing robbed his family of his precious sisters.

Mr. Doi’s elder sister, Yoshie, who was 13 and a second-year student at Hiroshima First Municipal Girls’ School (today’s Funairi High School), had left for Zaimoku-cho (now part of Naka Ward) to help tear down houses to create a fire lane. She never returned home. The following day, Mr. Doi walked around the hypocenter area with his neighbors, searching for her.

In the city center, everything had been destroyed and burnt to the ground. People roamed the landscape, desperately searching for loved ones. Others begged for water, including survivors with charred eyes and mouths and groups of female students, nearly naked. From the top to the bottom of the stone steps on both banks of the Honkawa River, there were stiff bodies with their heads thrown back and bodies with their arms spread wide, as if to embrace the sky. It was indeed a picture of hell.

Mr. Doi’s elder sister apparently died in the atomic bombing with about 540 first- and second-year students from Hiroshima First Municipal Girls’ School. Her remains were never found. His younger sister, Chizu, then 9, was pinned under a beam of a house that had collapsed when she was hit by the bomb blast on her way to a hospital in Yokogawa with her grandmother. As fire approached, the grandmother begged passersby for help, but no one stopped.

A few days later, Mr. Doi’s grandmother and mother located Chizu’s body, half-burned and buried. They gathered wood from trees and cremated the body there. His mother, who returned home with her daughter’s ashes, was likely in shock and did not cry. Even now the thought of Chizu suffering from the pain of being burned alive is heartbreaking.

Mr. Doi’s house, which was filled with memories of his family, was torn down about 40 years ago. He then donated a chest of drawers made of paulownia wood and pierced with numerous fragments of glass, like the fate that befell his mother, to the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum in 1999. Until this spring, the chest of drawers was on display at the museum, where it conveyed the destructive force of the bomb blast to visitors from Japan and around the world.

Now, a chozubachi (a water basin used to rinse the hands), which survived the atomic bombing from its spot in the garden, leaves a trace of that time on the site where his house once stood. A condominium now stands there, too. Last year, a gallery opened in the corner of the condominium. People from the community can display their art work and crafts there, creating opportunities for exchange.

Sharing his memories in an even tone, Mr. Doi said, “I don’t want to remember my experience of the atomic bombing. That’s all.” Then he added, “There must never be another war. Understanding one another and making connections between people is the foundation for peace.”

Teenagers’ Impressions

Lingering scars all his life

I think that Mr. Doi’s experience of the atomic bombing, which took place when he was three years younger than I am now, has left deep scars in his mind that have remained all his life. If I lost my family, I wouldn’t be able to endure the overwhelming sadness. He prepared his photos and the layout of his old house and shared his experience with us in earnest, though he repeatedly said, “I don’t want to talk about it.” He must have hesitated before deciding to speak to us. To make good use of Mr. Doi’s wish for peace, I want to convey his story to my family and friends. (Kotoori Kawagishi, 15)

Never want to see such a horrific sight

The Honkawa River is a familiar place to me because I walk along this river when I go to school. So I can still hear Mr. Doi’s voice as he recalled how the “Corpses were piled up on the stone steps of the riverbanks.” After the interview, when I stood there, I couldn’t imagine the horrific sight that Mr. Doi witnessed, because the view of the river is beautiful now. Still, I want to feel deeper empathy for the experiences of the A-bomb survivors by visiting the places that are mentioned in their accounts and by looking at photos from that time. (Shiho Fujii, 15)

(Originally published on August 8, 2017)

by Miho Kuwajima, Staff Writer

Hiroshi Doi, 83, lost his elder and younger sisters in the atomic bombing. He worked as an engineer for 40 years at Shinko Industries, a local manufacturer in Minami Ward that makes marine pumps and turbines. He wrote down his memories of the horrific experience he endured at the age of 11, but he would not talk about it, not even to his family. This summer, 72 years after the atomic bombing, he began talking about his experience in public for the first time.

Back then, Mr. Doi was a sixth grader at Misasa National School (now Misasa Elementary School). On August 6, 1945, he was ill and at home in Mitaki-machi (now part of Nishi Ward), about 2.5 kilometers from the hypocenter. While resting in the living room after having breakfast, he was suddenly knocked to the floor by a tremendous blast, and plaster and boards came tumbling down.

Amid heavy dust, Mr. Doi rose fearfully and found that he had miraculously escaped injury, but his mother, right near him, was covered in blood. Fragments of shattered glass had been hurled through the air and were piercing the right side of her upper body, including her head, arm, and chest. He thought that the house had been hit directly by a bomb. He donned an air-raid hood and, with his younger brother and youngest sister, fled to the terraced fields of a hill behind his house. He watched as the school buildings of Misasa National School, which he attended, were engulfed in flames and collapsed.

Mr. Doi was the second of five siblings. He had an elder sister, two younger sisters, and a younger brother. His father, who had run an ironworks before the war, was drafted into the Japanese Navy as an engineer in December 1941 and was killed in battle on the Gilbert Islands in November 1943. Moreover, the atomic bombing robbed his family of his precious sisters.

Mr. Doi’s elder sister, Yoshie, who was 13 and a second-year student at Hiroshima First Municipal Girls’ School (today’s Funairi High School), had left for Zaimoku-cho (now part of Naka Ward) to help tear down houses to create a fire lane. She never returned home. The following day, Mr. Doi walked around the hypocenter area with his neighbors, searching for her.

In the city center, everything had been destroyed and burnt to the ground. People roamed the landscape, desperately searching for loved ones. Others begged for water, including survivors with charred eyes and mouths and groups of female students, nearly naked. From the top to the bottom of the stone steps on both banks of the Honkawa River, there were stiff bodies with their heads thrown back and bodies with their arms spread wide, as if to embrace the sky. It was indeed a picture of hell.

Mr. Doi’s elder sister apparently died in the atomic bombing with about 540 first- and second-year students from Hiroshima First Municipal Girls’ School. Her remains were never found. His younger sister, Chizu, then 9, was pinned under a beam of a house that had collapsed when she was hit by the bomb blast on her way to a hospital in Yokogawa with her grandmother. As fire approached, the grandmother begged passersby for help, but no one stopped.

A few days later, Mr. Doi’s grandmother and mother located Chizu’s body, half-burned and buried. They gathered wood from trees and cremated the body there. His mother, who returned home with her daughter’s ashes, was likely in shock and did not cry. Even now the thought of Chizu suffering from the pain of being burned alive is heartbreaking.

Mr. Doi’s house, which was filled with memories of his family, was torn down about 40 years ago. He then donated a chest of drawers made of paulownia wood and pierced with numerous fragments of glass, like the fate that befell his mother, to the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum in 1999. Until this spring, the chest of drawers was on display at the museum, where it conveyed the destructive force of the bomb blast to visitors from Japan and around the world.

Now, a chozubachi (a water basin used to rinse the hands), which survived the atomic bombing from its spot in the garden, leaves a trace of that time on the site where his house once stood. A condominium now stands there, too. Last year, a gallery opened in the corner of the condominium. People from the community can display their art work and crafts there, creating opportunities for exchange.

Sharing his memories in an even tone, Mr. Doi said, “I don’t want to remember my experience of the atomic bombing. That’s all.” Then he added, “There must never be another war. Understanding one another and making connections between people is the foundation for peace.”

Teenagers’ Impressions

Lingering scars all his life

I think that Mr. Doi’s experience of the atomic bombing, which took place when he was three years younger than I am now, has left deep scars in his mind that have remained all his life. If I lost my family, I wouldn’t be able to endure the overwhelming sadness. He prepared his photos and the layout of his old house and shared his experience with us in earnest, though he repeatedly said, “I don’t want to talk about it.” He must have hesitated before deciding to speak to us. To make good use of Mr. Doi’s wish for peace, I want to convey his story to my family and friends. (Kotoori Kawagishi, 15)

Never want to see such a horrific sight

The Honkawa River is a familiar place to me because I walk along this river when I go to school. So I can still hear Mr. Doi’s voice as he recalled how the “Corpses were piled up on the stone steps of the riverbanks.” After the interview, when I stood there, I couldn’t imagine the horrific sight that Mr. Doi witnessed, because the view of the river is beautiful now. Still, I want to feel deeper empathy for the experiences of the A-bomb survivors by visiting the places that are mentioned in their accounts and by looking at photos from that time. (Shiho Fujii, 15)

(Originally published on August 8, 2017)