Survivors’ Stories: Hiroshi Hisanaga, 83, Nishi Ward, Hiroshima

Nov. 6, 2017

Father was bloodied by flying glass, but survived to rebuild the family business

by Miho Kuwajima, Staff Writer

Hiroshi Hisanaga, 83, an advisor to Rekiseisha, a local manufacturer that makes wallpaper of gold and silver leaf, retired from his position as president of this company 12 years ago, but every year he talks about his experience of the atomic bombing in front of its employees. He said, “If I don’t convey my experience, it will fade away. I have to send out messages of peace.”

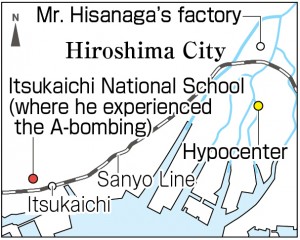

Back then, Mr. Hisanaga was a fifth grader at Itsukaichi National School (now Itsukaichi Elementary School). His father, Seijiro Hisanaga, operated a factory in Misasa-honmachi (now part of Nishi Ward), where the current company is located, and Mr. Hisanaga stayed with his maternal relatives in Itsukaichi-cho (now part of Saeki Ward) in the event of an air raid attack on the city center.

On the morning of August 6, 1945, the Monday morning assembly ended and Mr. Hisanaga was on his way back to his classroom after forming a group in the schoolyard. Suddenly, there was a flash of blinding light in the eastern sky. He remembers it as a brilliant flash. His teacher told the students to get down. Hearing the teacher’s cry, he instinctively put his hands over his eyes and nose, and dropped to his stomach.

Although Itsukaichi-cho was located far from the hypocenter, it was heavily damaged by the A-bomb blast. After a while, when Mr. Hisanaga raised his head, he found that the windows of the classroom were shattered and there were pieces of glass stuck in the skin of a few students.

Mr. Hisanaga’s parents, grandmother, sister, uncle, and some employees were at his home, 2.2 kilometers from the hypocenter. Later, he heard from his father that at the very moment when the atomic bomb exploded, there was a great boom, and the ceilings and windows of the factory and his house were blown off these buildings. Half of his father’s arm was cut by flying fragments of glass and he was bleeding heavily.

His father was in a half-conscious state and said, “Forget about me. I’ll share the same fate with this factory. Run! Quick!” He would not move, but Mr. Hisanaga’s mother desperately put him on a futon and dragged him out. His father was brought to a temporary aid station and managed to survive. But Mr. Hisanaga’s grandmother, who was in a state of shock from the sight of her son covered in blood, passed away while fleeing the area.

On August 14, the day before the war ended, Mr. Hisanaga returned home from his evacuation site. He was exposed to the atomic bomb’s radiation after entering the city area in the aftermath of the bombing. More than one week had passed since the attack, but there was still smoke from smoldering fires across the devastated city, and large numbers of bodies infected with maggots were lying on the ground. The smell was appalling.

The five-story factory and Mr. Hisanaga’s house standing next to it were reduced to ashes, and a 27-meter-high chimney and storage unit stood in the charred ruins. Mr. Hisanaga said that an unutterable loneliness welled up in him. Looking back on those days, he said, “I feel I have been burdened by my experience of the atomic bombing ever since I became old enough to understand what was going on around me.”

Mr. Hisanaga’s father gradually recovered and extended his business by making waterproof materials for roofs and creating paints for wooden ships with pine oil during a postwar era of shortages. Mr. Hisanaga said, “We didn’t have any textbooks, and there were only desks and blackboards at school, which was not a conducive environment for learning.”

Still, Mr. Hisanaga graduated from Hiroshima University and began working at his father’s company, then took over the management of the business from his brother in 1981. He has carefully preserved the chimney and storage unit that survived the atomic bombing so that he will not forget his family members’ experiences and hardships. The company still uses the chimney, a precious A-bombed structure, as a ventilation hole. The wallpaper produced at this factory is used in and out of Japan, including at the Imperial Hotel.

To leave evidence that the company again started from scratch, Mr. Hisanaga embedded part of a stone lantern with scars from scorching, which stood inside the grounds at the time of the atomic bombing, in the entrance of the showroom which was newly established in 1993.

Mr. Hisanaga said, “The great efforts made by my father and mother created a new history. My wish for a peaceful world is very strong because I have experienced the atomic bombing.” Now the the sixth-generation president of the company, Mr. Hisanaga will surely continue talking about the atomic bombing as long as he lives.

Teenagers’ impressions

The city’s recovery is an important memory

After the war, Mr. Hisanaga’s father, whose factory was completely destroyed in the atomic bombing, restarted making wallpaper of gold leaf with the members of his family, after manufacturing waterproof materials for roofs, and gradually made his business a success. Mr. Hisanaga said, “Gold has the power to make people feel peace or hope.” Restarting the business is a symbol of peace or recovery, and this must have been people’s wish. I felt that the city’s recovery is part of the memories of Hiroshima. (Miki Meguro, 14)

Feeling gratitude for school and meals

Mr. Hisanaga said, his eyes shining, “The rice I ate after the war was so delicious.” I was impressed by these words. The food shortage during the war must have been so severe. Mr. Hisanaga had to study outdoors because the roof of the school building was blown off and the glass panes of the windows were shattered by the blast of the bomb. We can study in a good environment and we live in an age of material abundance. I want to live with a sense of gratitude for everything, such as school life and food. (Riho Kito, 16)

(Originally published on November 6, 2017)

by Miho Kuwajima, Staff Writer

Hiroshi Hisanaga, 83, an advisor to Rekiseisha, a local manufacturer that makes wallpaper of gold and silver leaf, retired from his position as president of this company 12 years ago, but every year he talks about his experience of the atomic bombing in front of its employees. He said, “If I don’t convey my experience, it will fade away. I have to send out messages of peace.”

Back then, Mr. Hisanaga was a fifth grader at Itsukaichi National School (now Itsukaichi Elementary School). His father, Seijiro Hisanaga, operated a factory in Misasa-honmachi (now part of Nishi Ward), where the current company is located, and Mr. Hisanaga stayed with his maternal relatives in Itsukaichi-cho (now part of Saeki Ward) in the event of an air raid attack on the city center.

On the morning of August 6, 1945, the Monday morning assembly ended and Mr. Hisanaga was on his way back to his classroom after forming a group in the schoolyard. Suddenly, there was a flash of blinding light in the eastern sky. He remembers it as a brilliant flash. His teacher told the students to get down. Hearing the teacher’s cry, he instinctively put his hands over his eyes and nose, and dropped to his stomach.

Although Itsukaichi-cho was located far from the hypocenter, it was heavily damaged by the A-bomb blast. After a while, when Mr. Hisanaga raised his head, he found that the windows of the classroom were shattered and there were pieces of glass stuck in the skin of a few students.

Mr. Hisanaga’s parents, grandmother, sister, uncle, and some employees were at his home, 2.2 kilometers from the hypocenter. Later, he heard from his father that at the very moment when the atomic bomb exploded, there was a great boom, and the ceilings and windows of the factory and his house were blown off these buildings. Half of his father’s arm was cut by flying fragments of glass and he was bleeding heavily.

His father was in a half-conscious state and said, “Forget about me. I’ll share the same fate with this factory. Run! Quick!” He would not move, but Mr. Hisanaga’s mother desperately put him on a futon and dragged him out. His father was brought to a temporary aid station and managed to survive. But Mr. Hisanaga’s grandmother, who was in a state of shock from the sight of her son covered in blood, passed away while fleeing the area.

On August 14, the day before the war ended, Mr. Hisanaga returned home from his evacuation site. He was exposed to the atomic bomb’s radiation after entering the city area in the aftermath of the bombing. More than one week had passed since the attack, but there was still smoke from smoldering fires across the devastated city, and large numbers of bodies infected with maggots were lying on the ground. The smell was appalling.

The five-story factory and Mr. Hisanaga’s house standing next to it were reduced to ashes, and a 27-meter-high chimney and storage unit stood in the charred ruins. Mr. Hisanaga said that an unutterable loneliness welled up in him. Looking back on those days, he said, “I feel I have been burdened by my experience of the atomic bombing ever since I became old enough to understand what was going on around me.”

Mr. Hisanaga’s father gradually recovered and extended his business by making waterproof materials for roofs and creating paints for wooden ships with pine oil during a postwar era of shortages. Mr. Hisanaga said, “We didn’t have any textbooks, and there were only desks and blackboards at school, which was not a conducive environment for learning.”

Still, Mr. Hisanaga graduated from Hiroshima University and began working at his father’s company, then took over the management of the business from his brother in 1981. He has carefully preserved the chimney and storage unit that survived the atomic bombing so that he will not forget his family members’ experiences and hardships. The company still uses the chimney, a precious A-bombed structure, as a ventilation hole. The wallpaper produced at this factory is used in and out of Japan, including at the Imperial Hotel.

To leave evidence that the company again started from scratch, Mr. Hisanaga embedded part of a stone lantern with scars from scorching, which stood inside the grounds at the time of the atomic bombing, in the entrance of the showroom which was newly established in 1993.

Mr. Hisanaga said, “The great efforts made by my father and mother created a new history. My wish for a peaceful world is very strong because I have experienced the atomic bombing.” Now the the sixth-generation president of the company, Mr. Hisanaga will surely continue talking about the atomic bombing as long as he lives.

Teenagers’ impressions

The city’s recovery is an important memory

After the war, Mr. Hisanaga’s father, whose factory was completely destroyed in the atomic bombing, restarted making wallpaper of gold leaf with the members of his family, after manufacturing waterproof materials for roofs, and gradually made his business a success. Mr. Hisanaga said, “Gold has the power to make people feel peace or hope.” Restarting the business is a symbol of peace or recovery, and this must have been people’s wish. I felt that the city’s recovery is part of the memories of Hiroshima. (Miki Meguro, 14)

Feeling gratitude for school and meals

Mr. Hisanaga said, his eyes shining, “The rice I ate after the war was so delicious.” I was impressed by these words. The food shortage during the war must have been so severe. Mr. Hisanaga had to study outdoors because the roof of the school building was blown off and the glass panes of the windows were shattered by the blast of the bomb. We can study in a good environment and we live in an age of material abundance. I want to live with a sense of gratitude for everything, such as school life and food. (Riho Kito, 16)

(Originally published on November 6, 2017)