Survivors’ Stories: Sachiko Tanaka, 88, Hatsukaichi City

Dec. 4, 2017

A-bombed dictionary is donated to Peace Memorial Museum

by Yuji Yamamoto, Staff Writer

Sachiko Tanaka (née Okamoto), 88, donated the battered Japanese dictionary “Kojirin” to the Peace Memorial Museum this past summer. It was the dictionary she took from home and fled with on the day of the atomic bombing. She was 16 years old at the time. She used the dictionary regularly even after the war, and finally decided to entrust it to the museum, thinking that it should continue to be preserved. Her own life is linked to the dictionary, she says. “It survived the flames and lived with me for so long.”

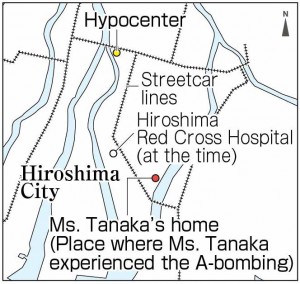

Ms. Tanaka was a student in the advanced course at Yasuda Girls’ High School (now Yasuda Girls’ Junior High School and High School). On August 6, 1945, she was sick and took the day off from working as a mobilized student. She was studying at home in Hirano-machi (now Naka Ward), about 1.8 kilometers from the hypocenter, when she was exposed to a sudden whitish-blue flash of light. When she came to, she found herself crouched down under the desk with the dictionary in her hand.

The house had collapsed around her and Ms. Tanaka stuck her head up through the roof. When she called for help, a man pulled her out, along with the dictionary, and then took off. Ms. Tanaka’s mother, Kikuyo, who was hanging out the laundry, stood stockstill. The upper half of her body had been burned. The houses all around were also destroyed. Across the wreckage, Hijiyama Hill could now be seen clearly and it had never appeared so close. Ms. Tanaka stood there in a daze. Then a man whose face was burnt and was naked down to his waist approached her and said, “It’s me.” Ms. Tanaka recognized the voice. It was her father, Tamaichi, who had left for work that morning.

Ms. Tanaka’s family fled to the grounds of Hiroshima University of Literature and Science (now Hiroshima University). When they went back home in the evening, they found that their toppled home had escaped the flames and her uncle was waiting there. Ms. Tanaka’s cousin, who was a year younger than she was, lay at his feet. He said, “She’s dead. We have to cremate her.” The family helped him prepare for the cremation. As the body was burning, Ms. Tanaka saw it shudder in the fire for an instant. “Uncle, she’s still alive!” Ms. Tanaka told him. But he replied, “No, she’s dead.” She was strangely convinced by his words. The family gathered up her ashes the next day.

Ms. Tanaka took her parents to Hiroshima Red Cross Hospital (now Hiroshima Red Cross Hospital & Atomic Bomb Survivors Hospital) for treatment, but all the doctors could do was apply some antiseptic. Around August 9, another cousin came searching for them. Ms. Tanaka put her parents on a two-wheeled handcart and brought them to Kujimamura (now in Hatsukaichi City), where her maternal grandparents lived.

Ms. Tanaka’s parents suffered from acute radiation sickness and developed purple spots on their bodies, but they managed to survive and their condition improved. Then, in just one day, all of Ms. Tanaka’s hair fell out. She was distraught, but her cousin encouraged her and wrapped her head in a traditional Japanese wrapping cloth. About six months later, her hair began to grow in again. Looking back, she said that was one of the happiest moments of her life.

Ms. Tanaka went on to college after the war and became an elementary school teacher. However, she was turned down when her family tried to arrange a marriage for her. Then, at the age of 26, Ms. Tanaka married Inagi, who was also an A-bomb survivor. When she became pregnant with their first child, the couple worried about the baby’s health and were torn over whether to have the child. Fortunately, the baby girl was born without any concerns and they were also blessed with a son four years later.

Ms. Tanaka is unable to stop faulting herself for surviving that day while so many others died. She sometimes suffers nightmares involving the scene where she experienced her cousin being cremated. In the dream, she always apologizes.

After her husband passed away in 1984, Ms. Tanaka devoted herself to composing tanka, a short form of Japanese poem that consists of 31 syllables. Her important partner in these efforts was the Kojirin dictionary that her father once bought for her. It was published in 1941, the year that the war between Japan and the United States broke out. Even when blackouts became part of the wartime experience, she would look through her dictionary in bed with a flashlight in hand.

As she consulted the dictionary, she discovered new words and came to write down tanka poems in more than 100 notebooks. Her passion for composing tanka hasn’t diminished, even after the left side of her body became paralyzed due to Parkinson’s disease.

“The atomic bombing might not be seen as a big deal because the Japanese government doesn’t oppose the production of nuclear arms.”

When the Japanese government took a stand against the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, which was adopted at the United Nations this past July, Ms. Tanaka wrote the poem above to express her indignation.

“The only reason I’m still alive is to see nuclear weapons and war eliminated from the Earth,” Ms. Tanaka said. To express this desire, and her feelings that have grown stronger each day, she placed a new dictionary in front of her and opened her notebook.

Teenagers’ Impressions

The atomic bombing left scars in her heart

Ms. Tanaka told us that she couldn’t help asking a nurse if her baby had eyes, ears, and arms when she gave birth to her daughter. That’s how worried she was about the influence of the atomic bombing on her children. The war has left emotional scars in the hearts of so many people. The same thing can be said for quarrels that take place in daily life. I now realize how important it is for each of us not to fight with our loved ones. (Kota Ueda, 14)

War changes human beings into demons

Ms. Tanaka said that she lost the heart of a human being when she experienced the atomic bombing. She regrets that they rushed to cremate her cousin’s body amid the chaos after the A-bomb attack. She also believed it would be an honor to die during the war, a way of thinking that’s unimaginable in our times. War changes human beings into demons. In order to stay human, we must never make war. (Yukiho Saito, 15)

(Originally published on December 4, 2017)

by Yuji Yamamoto, Staff Writer

Sachiko Tanaka (née Okamoto), 88, donated the battered Japanese dictionary “Kojirin” to the Peace Memorial Museum this past summer. It was the dictionary she took from home and fled with on the day of the atomic bombing. She was 16 years old at the time. She used the dictionary regularly even after the war, and finally decided to entrust it to the museum, thinking that it should continue to be preserved. Her own life is linked to the dictionary, she says. “It survived the flames and lived with me for so long.”

Ms. Tanaka was a student in the advanced course at Yasuda Girls’ High School (now Yasuda Girls’ Junior High School and High School). On August 6, 1945, she was sick and took the day off from working as a mobilized student. She was studying at home in Hirano-machi (now Naka Ward), about 1.8 kilometers from the hypocenter, when she was exposed to a sudden whitish-blue flash of light. When she came to, she found herself crouched down under the desk with the dictionary in her hand.

The house had collapsed around her and Ms. Tanaka stuck her head up through the roof. When she called for help, a man pulled her out, along with the dictionary, and then took off. Ms. Tanaka’s mother, Kikuyo, who was hanging out the laundry, stood stockstill. The upper half of her body had been burned. The houses all around were also destroyed. Across the wreckage, Hijiyama Hill could now be seen clearly and it had never appeared so close. Ms. Tanaka stood there in a daze. Then a man whose face was burnt and was naked down to his waist approached her and said, “It’s me.” Ms. Tanaka recognized the voice. It was her father, Tamaichi, who had left for work that morning.

Ms. Tanaka’s family fled to the grounds of Hiroshima University of Literature and Science (now Hiroshima University). When they went back home in the evening, they found that their toppled home had escaped the flames and her uncle was waiting there. Ms. Tanaka’s cousin, who was a year younger than she was, lay at his feet. He said, “She’s dead. We have to cremate her.” The family helped him prepare for the cremation. As the body was burning, Ms. Tanaka saw it shudder in the fire for an instant. “Uncle, she’s still alive!” Ms. Tanaka told him. But he replied, “No, she’s dead.” She was strangely convinced by his words. The family gathered up her ashes the next day.

Ms. Tanaka took her parents to Hiroshima Red Cross Hospital (now Hiroshima Red Cross Hospital & Atomic Bomb Survivors Hospital) for treatment, but all the doctors could do was apply some antiseptic. Around August 9, another cousin came searching for them. Ms. Tanaka put her parents on a two-wheeled handcart and brought them to Kujimamura (now in Hatsukaichi City), where her maternal grandparents lived.

Ms. Tanaka’s parents suffered from acute radiation sickness and developed purple spots on their bodies, but they managed to survive and their condition improved. Then, in just one day, all of Ms. Tanaka’s hair fell out. She was distraught, but her cousin encouraged her and wrapped her head in a traditional Japanese wrapping cloth. About six months later, her hair began to grow in again. Looking back, she said that was one of the happiest moments of her life.

Ms. Tanaka went on to college after the war and became an elementary school teacher. However, she was turned down when her family tried to arrange a marriage for her. Then, at the age of 26, Ms. Tanaka married Inagi, who was also an A-bomb survivor. When she became pregnant with their first child, the couple worried about the baby’s health and were torn over whether to have the child. Fortunately, the baby girl was born without any concerns and they were also blessed with a son four years later.

Ms. Tanaka is unable to stop faulting herself for surviving that day while so many others died. She sometimes suffers nightmares involving the scene where she experienced her cousin being cremated. In the dream, she always apologizes.

After her husband passed away in 1984, Ms. Tanaka devoted herself to composing tanka, a short form of Japanese poem that consists of 31 syllables. Her important partner in these efforts was the Kojirin dictionary that her father once bought for her. It was published in 1941, the year that the war between Japan and the United States broke out. Even when blackouts became part of the wartime experience, she would look through her dictionary in bed with a flashlight in hand.

As she consulted the dictionary, she discovered new words and came to write down tanka poems in more than 100 notebooks. Her passion for composing tanka hasn’t diminished, even after the left side of her body became paralyzed due to Parkinson’s disease.

“The atomic bombing might not be seen as a big deal because the Japanese government doesn’t oppose the production of nuclear arms.”

When the Japanese government took a stand against the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, which was adopted at the United Nations this past July, Ms. Tanaka wrote the poem above to express her indignation.

“The only reason I’m still alive is to see nuclear weapons and war eliminated from the Earth,” Ms. Tanaka said. To express this desire, and her feelings that have grown stronger each day, she placed a new dictionary in front of her and opened her notebook.

Teenagers’ Impressions

The atomic bombing left scars in her heart

Ms. Tanaka told us that she couldn’t help asking a nurse if her baby had eyes, ears, and arms when she gave birth to her daughter. That’s how worried she was about the influence of the atomic bombing on her children. The war has left emotional scars in the hearts of so many people. The same thing can be said for quarrels that take place in daily life. I now realize how important it is for each of us not to fight with our loved ones. (Kota Ueda, 14)

War changes human beings into demons

Ms. Tanaka said that she lost the heart of a human being when she experienced the atomic bombing. She regrets that they rushed to cremate her cousin’s body amid the chaos after the A-bomb attack. She also believed it would be an honor to die during the war, a way of thinking that’s unimaginable in our times. War changes human beings into demons. In order to stay human, we must never make war. (Yukiho Saito, 15)

(Originally published on December 4, 2017)