Survivors’ Stories: Sadae Kasaoka, 85, Nishi Ward, Hiroshima

Feb. 6, 2018

Father suffered terrible burns and passed away with his family around him

by Miho Kuwajima, Staff Writer

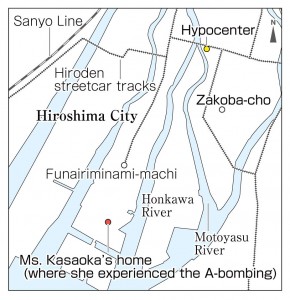

Sadae Kasaoka (née Hiraoka), 85, experienced the atomic bombing while at home in Eba-machi (now part of Naka Ward), 3.5 kilometers from the hypocenter. Both of her parents lost their lives as a result of the A-bomb attack. Her brother, Kichitaro Hiraoka, 92, has preserved the gate at the home where her parents once lived. He said, “The gate is living proof of my parents and my deep bitterness over the atomic bombing, which stole them away.”

August 6, 1945 was a bright, clear day. Her father, Shinajiro (then 52), and her mother, Kichi (then 49), left home early in the morning to help an acquaintance tear down buildings to create a fire lane in Zakoba-cho (now part of Naka Ward). Ms. Kasaoka, who was a first-year student at Shintoku Girls’ High School, stayed home with her grandmother because that was a day she wasn’t mobilized for work.

The moment she reentered the house after hanging up laundry out in the yard, there was a flash of orange light. In the next instant, the windows shattered and broken glass flew at her. She quickly dropped to the floor, but when she touched her head, she found that her hand was smeared with blood. She rushed into an air raid shelter with her grandmother.

Ms. Kasaoka was worried about her parents, who were in Zakoba-cho, about 1 kilometer from the hypocenter. In the evening, she heard that her father had taken refuge at a relative’s home in the Oko district (now part of Minami Ward), and Kichitaro, who had happened to return from Osaka, where he attended school, went to pick him up.

The following morning, her father, who was brought back home on a two-wheel cart, looked like a completely different person. His face was swollen and his whole body was charred black. When Ms. Kasaoka touched him, the skin on his body peeled right off, revealing his red flesh. He said, “I ran away with Kichi but got lost along the way. Search for her.” She was able to recognize her father only by the sound of his voice.

The wounds that festered became infested with maggots. Ms. Kasaoka’s father loved to drink alcohol, so she tried to give him beer, which had been hidden in the shed, but the beer only spilled from his mouth. He murmured in a state of delirium and his body trembled. After suffering for two days, he passed away on the evening of August 8. They dug a hole at a nearby beach, gathered pieces of wood, and cremated him.

Her mother was not found right away. On the morning of August 9, Ms. Kasaoka heard that Kichi had been at an aid station located at the quarantine station on Ninoshima Island. Kichitaro headed there immediately. But Kichi had already died, and been cremated. Ms. Kasaoka saw only bone fragments from her mother’s body, held in a small paper bag that her brother brought back with him.

After the war ended, Kichitaro left a branch school of a nautical college and worked for the Maritime Safety Agency while raising Ms. Kasaoka and his siblings. Day by day, they struggled to make ends meet, and she sometimes sold oysters and figs that she gathered.

Ms. Kasaoka instinctively avoided talking about her parents with her schoolmates. But looking back on those days, she said, “I had my grandmother and my brother, but there were A-bomb orphans who had no relatives at all. Even when it was cold, they were sleeping outside. Their lives were more miserable than mine.”

After the war, Ms. Kasaoka entered, and graduated from, a different school, then took a position at the Hiroshima Prefectural Office. At the age of 24, she accepted an arranged marriage with an A-bomb survivor and had a son and a daughter. But when the children were very young, her husband passed away, probably due to the aftereffects of his exposure to the atomic bomb.

Nevertheless, she continued to work as an employee of the prefectural government while raising her two children. With support from the people around her, she was able to go on living her life. To repay the kindness that others showed to her, she has offered her support to the activities of the local Girl Scouts for many years. She also registered as an A-bomb witness with the City of Hiroshima in 2005, and began to share her experience of the Hiroshima bombing with overseas visitors and students on school trips.

“None of those who died wanted to die. Along with their lives, the atomic bomb stole away people’s hopes and dreams for the future,” Ms. Kasaoka said, resolved to continue speaking to children about the tragedy of war and the importance of loving others.

Teenagers’ impressions

The importance of daily life with family

When I asked Ms. Kasaoka what was the hardest thing after the war, she said that she couldn’t think about the future in those days. On the other hand, she felt very sad because she had no parents to say to her, “Hello, how was your day?” when she came home. If my parents died, I wouldn’t know what to do and I would go on crying forever. I want to value daily life with my precious parents and brother and make it a habit to properly greet the people around me. (Atsuhito Ito, 14)

Want to work with others to help abolish nuclear weapons

I was particularly moved by Ms. Kasaoka’s description of her father, who had been charred black by the bomb’s heat rays. She showed us the image of a painting that a student at Motomachi High School had made, based on her account. I had a feeling of horror as I looked at the vivid image of her father’s turned-up lips and eyeballs that had popped from their sockets. I tried to imagine what that would be like, by putting myself in her shoes, but I couldn’t really grasp the reality. I felt strongly that we have to take over her wish that others should not experience what she did and that we have to take action with others to help abolish nuclear weapons from the world. (Hisashi Iwata, 16)

(Originally published on February 6, 2018)

by Miho Kuwajima, Staff Writer

Sadae Kasaoka (née Hiraoka), 85, experienced the atomic bombing while at home in Eba-machi (now part of Naka Ward), 3.5 kilometers from the hypocenter. Both of her parents lost their lives as a result of the A-bomb attack. Her brother, Kichitaro Hiraoka, 92, has preserved the gate at the home where her parents once lived. He said, “The gate is living proof of my parents and my deep bitterness over the atomic bombing, which stole them away.”

August 6, 1945 was a bright, clear day. Her father, Shinajiro (then 52), and her mother, Kichi (then 49), left home early in the morning to help an acquaintance tear down buildings to create a fire lane in Zakoba-cho (now part of Naka Ward). Ms. Kasaoka, who was a first-year student at Shintoku Girls’ High School, stayed home with her grandmother because that was a day she wasn’t mobilized for work.

The moment she reentered the house after hanging up laundry out in the yard, there was a flash of orange light. In the next instant, the windows shattered and broken glass flew at her. She quickly dropped to the floor, but when she touched her head, she found that her hand was smeared with blood. She rushed into an air raid shelter with her grandmother.

Ms. Kasaoka was worried about her parents, who were in Zakoba-cho, about 1 kilometer from the hypocenter. In the evening, she heard that her father had taken refuge at a relative’s home in the Oko district (now part of Minami Ward), and Kichitaro, who had happened to return from Osaka, where he attended school, went to pick him up.

The following morning, her father, who was brought back home on a two-wheel cart, looked like a completely different person. His face was swollen and his whole body was charred black. When Ms. Kasaoka touched him, the skin on his body peeled right off, revealing his red flesh. He said, “I ran away with Kichi but got lost along the way. Search for her.” She was able to recognize her father only by the sound of his voice.

The wounds that festered became infested with maggots. Ms. Kasaoka’s father loved to drink alcohol, so she tried to give him beer, which had been hidden in the shed, but the beer only spilled from his mouth. He murmured in a state of delirium and his body trembled. After suffering for two days, he passed away on the evening of August 8. They dug a hole at a nearby beach, gathered pieces of wood, and cremated him.

Her mother was not found right away. On the morning of August 9, Ms. Kasaoka heard that Kichi had been at an aid station located at the quarantine station on Ninoshima Island. Kichitaro headed there immediately. But Kichi had already died, and been cremated. Ms. Kasaoka saw only bone fragments from her mother’s body, held in a small paper bag that her brother brought back with him.

After the war ended, Kichitaro left a branch school of a nautical college and worked for the Maritime Safety Agency while raising Ms. Kasaoka and his siblings. Day by day, they struggled to make ends meet, and she sometimes sold oysters and figs that she gathered.

Ms. Kasaoka instinctively avoided talking about her parents with her schoolmates. But looking back on those days, she said, “I had my grandmother and my brother, but there were A-bomb orphans who had no relatives at all. Even when it was cold, they were sleeping outside. Their lives were more miserable than mine.”

After the war, Ms. Kasaoka entered, and graduated from, a different school, then took a position at the Hiroshima Prefectural Office. At the age of 24, she accepted an arranged marriage with an A-bomb survivor and had a son and a daughter. But when the children were very young, her husband passed away, probably due to the aftereffects of his exposure to the atomic bomb.

Nevertheless, she continued to work as an employee of the prefectural government while raising her two children. With support from the people around her, she was able to go on living her life. To repay the kindness that others showed to her, she has offered her support to the activities of the local Girl Scouts for many years. She also registered as an A-bomb witness with the City of Hiroshima in 2005, and began to share her experience of the Hiroshima bombing with overseas visitors and students on school trips.

“None of those who died wanted to die. Along with their lives, the atomic bomb stole away people’s hopes and dreams for the future,” Ms. Kasaoka said, resolved to continue speaking to children about the tragedy of war and the importance of loving others.

Teenagers’ impressions

The importance of daily life with family

When I asked Ms. Kasaoka what was the hardest thing after the war, she said that she couldn’t think about the future in those days. On the other hand, she felt very sad because she had no parents to say to her, “Hello, how was your day?” when she came home. If my parents died, I wouldn’t know what to do and I would go on crying forever. I want to value daily life with my precious parents and brother and make it a habit to properly greet the people around me. (Atsuhito Ito, 14)

Want to work with others to help abolish nuclear weapons

I was particularly moved by Ms. Kasaoka’s description of her father, who had been charred black by the bomb’s heat rays. She showed us the image of a painting that a student at Motomachi High School had made, based on her account. I had a feeling of horror as I looked at the vivid image of her father’s turned-up lips and eyeballs that had popped from their sockets. I tried to imagine what that would be like, by putting myself in her shoes, but I couldn’t really grasp the reality. I felt strongly that we have to take over her wish that others should not experience what she did and that we have to take action with others to help abolish nuclear weapons from the world. (Hisashi Iwata, 16)

(Originally published on February 6, 2018)