Notebook that recorded medical treatment for Sadako Sasaki to be donated to the Peace Memorial Museum

Jul. 10, 2018

by Michiko Tanaka, Staff Writer

It has been learned that a doctor who cared for Sadako Sasaki kept a record of her fight against her A-bomb-induced leukemia and left this record behind when he died. Sadako is a girl who died of this illness 10 years after the atomic bombing. Her death, and the paper cranes she folded with the wish to recover, became the inspiration for the raising of the Children’s Peace Monument in the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park.

The record reveals how fervently Sadako sought to survive during her last 247 days and how the Hiroshima doctor made strenuous efforts to treat the A-bomb disease that developed long after the atomic bombing. Family members of the doctor hope to donate his notebook, in which he summarized her original medical record, to the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum.

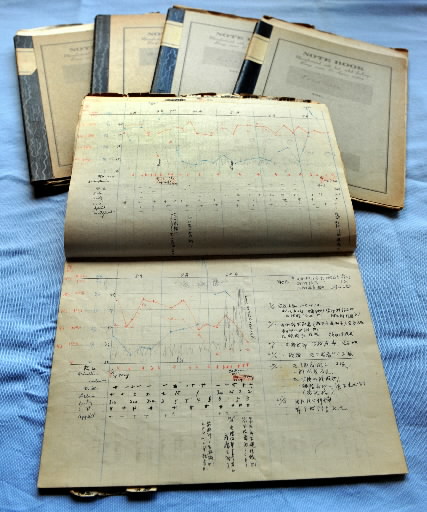

Joji Numata, who died in February at the age of 90, was Sadako’s doctor. Before Mr. Numata opened a clinic in Asaminami Ward in 1959, he served as the deputy chief of the pediatrics department at the Hiroshima Red Cross Hospital (now the Hiroshima Red Cross Hospital & Atomic-bomb Survivors Hospital). The cover of Dr. Numata’s notebook, now discolored to brown, reads “Leukemia.” In it, he summarized the medical records of 11 patients he was treating, including Sadako.

Dr. Numata made notes about Sadako on a total of eight pages. Her white cell count, body temperature, and the timing of her medication are listed during the period from February 21, 1955, the day she was hospitalized, to October 25, the day she died. Other information, such as whether or not she had an appetite and the amount of bleeding, are described in detail.

Chiharu Numata, 82, Dr. Numata’s wife, recalled, “My husband told me that Sadako was a very patient girl.” Mariko Kodama, 60, Dr. Numata’s eldest daughter and a pediatrician who followed in her father’s footsteps, assumed that her father had made use of the notebook to compile the data from his patients’ charts. He left behind four other notebooks which also summarize the medical records of additional patients and the features of the medications he used.

Along with the notebooks, a paper which Dr. Numata presented at an academic conference in 1956 has also been preserved. This paper reported on the fact that Sadako had developed thyroid cancer, too. According to the paper, very few cases of thyroid cancer in children were observed in Japan in those days. Meanwhile, in the United States, there were cases in which children developed thyroid cancer after undergoing X-ray examinations when they were babies. Citing Sadako’s case, Dr. Numata forcefully raised the possibility of a connection between exposure to radiation and the development of thyroid cancer.

Dr. Numata himself experienced the atomic bombing while at home in Gion-cho (now part of Asaminami Ward) after returning to Hiroshima from the medical school he was attending in Tokyo. His sister, who was three years younger, suffered severe burns at the time of the attack because she had been mobilized to help tear down homes to create a fire lane. She died two days after the bombing. Weighing her father’s feelings, Chiharu said, “I think my father’s experience of being at his sister’s deathbed may have compelled him to pursue his medical research.”

Koichiro Maeda, the director of the Peace Memorial Museum, said, “Dr. Numata’s notebook is a very precious record of that time. It shows how earnestly he carried out his work as a physician.” Masahiro Sasaki, 71, Sadako’s elder brother who lives in Fukuoka Prefecture, commented, “The notebook is evidence of my sister’s life. I hope it is preserved carefully in the museum.”

(Originally published on August 6, 2012)

It has been learned that a doctor who cared for Sadako Sasaki kept a record of her fight against her A-bomb-induced leukemia and left this record behind when he died. Sadako is a girl who died of this illness 10 years after the atomic bombing. Her death, and the paper cranes she folded with the wish to recover, became the inspiration for the raising of the Children’s Peace Monument in the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park.

The record reveals how fervently Sadako sought to survive during her last 247 days and how the Hiroshima doctor made strenuous efforts to treat the A-bomb disease that developed long after the atomic bombing. Family members of the doctor hope to donate his notebook, in which he summarized her original medical record, to the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum.

Joji Numata, who died in February at the age of 90, was Sadako’s doctor. Before Mr. Numata opened a clinic in Asaminami Ward in 1959, he served as the deputy chief of the pediatrics department at the Hiroshima Red Cross Hospital (now the Hiroshima Red Cross Hospital & Atomic-bomb Survivors Hospital). The cover of Dr. Numata’s notebook, now discolored to brown, reads “Leukemia.” In it, he summarized the medical records of 11 patients he was treating, including Sadako.

Dr. Numata made notes about Sadako on a total of eight pages. Her white cell count, body temperature, and the timing of her medication are listed during the period from February 21, 1955, the day she was hospitalized, to October 25, the day she died. Other information, such as whether or not she had an appetite and the amount of bleeding, are described in detail.

Chiharu Numata, 82, Dr. Numata’s wife, recalled, “My husband told me that Sadako was a very patient girl.” Mariko Kodama, 60, Dr. Numata’s eldest daughter and a pediatrician who followed in her father’s footsteps, assumed that her father had made use of the notebook to compile the data from his patients’ charts. He left behind four other notebooks which also summarize the medical records of additional patients and the features of the medications he used.

Along with the notebooks, a paper which Dr. Numata presented at an academic conference in 1956 has also been preserved. This paper reported on the fact that Sadako had developed thyroid cancer, too. According to the paper, very few cases of thyroid cancer in children were observed in Japan in those days. Meanwhile, in the United States, there were cases in which children developed thyroid cancer after undergoing X-ray examinations when they were babies. Citing Sadako’s case, Dr. Numata forcefully raised the possibility of a connection between exposure to radiation and the development of thyroid cancer.

Dr. Numata himself experienced the atomic bombing while at home in Gion-cho (now part of Asaminami Ward) after returning to Hiroshima from the medical school he was attending in Tokyo. His sister, who was three years younger, suffered severe burns at the time of the attack because she had been mobilized to help tear down homes to create a fire lane. She died two days after the bombing. Weighing her father’s feelings, Chiharu said, “I think my father’s experience of being at his sister’s deathbed may have compelled him to pursue his medical research.”

Koichiro Maeda, the director of the Peace Memorial Museum, said, “Dr. Numata’s notebook is a very precious record of that time. It shows how earnestly he carried out his work as a physician.” Masahiro Sasaki, 71, Sadako’s elder brother who lives in Fukuoka Prefecture, commented, “The notebook is evidence of my sister’s life. I hope it is preserved carefully in the museum.”

(Originally published on August 6, 2012)