Survivors’ Stories: Takanari Sakata, 89, Miyoshi: I couldn’t continue carrying the dead

May 6, 2019

by Yuji Yamamoto, Staff Writer

Takanari Sakata, 89, can never forget the dreadful sights he saw as he wandered through the city of Hiroshima in the aftermath of the atomic bombing. There were scores of bodies strewn everywhere. “I was lucky that I didn’t die, too,” he said. His gratitude for having survived has been a motivating force in his efforts to make the city of Miyoshi, his hometown, a positive place to live.

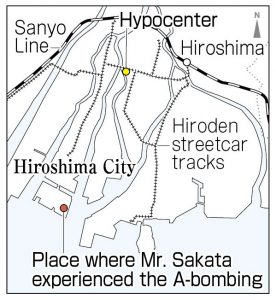

Mr. Sakata left his home in the village of Itaki in Hiroshima Prefecture (now part of Miwa-cho, Miyoshi City) to enter Shudo Junior High School in Hiroshima. He was 15 years old, in his fourth year of junior high school, when he experienced the atomic bombing while at the Hiroshima Shipyard of Mitsubishi Heavy Industries in Ebamachi (now part of Naka Ward), located about 3.7 kilometers from the hypocenter. At the time, he was mobilized for the war effort and was helping to install equipment on transport ships. He commuted by ferry from Miyajima, where his dormitory was located.

On the morning of August 6, 1945, he was at the Hiroshima Shipyard plant. The morning assembly had just finished when a blinding flash poured through the window. About 10 seconds later, his body was shaken by the bomb blast and he dove to the floor. Though his neck was cut by a piece of falling slate, he escaped serious injury.

He headed to the plant’s infirmary, thinking, “Maybe an armory in the city exploded.” There was blood all over the infirmary because pieces of glass had pierced the factory workers and nurses. The sky was glowing red, with a huge bud-shaped cloud rising in the sky. The factory workers were dragging their feet as they walked under the cloud. Mr. Sakata was dismayed and he waited for a ferry until that evening to return to his dormitory.

On the following day, August 7, Mr. Sakata went back into the city to look for his uncle, who had begun a new post at the Hiroshima Army Hospital. Injured people approached him, pleading for water, but he was unable to help them. He glanced to one side and saw a pile of bodies being cremated, but he went on walking. “It’s impossible to put that terrible scene into words,” Mr. Sakata said, as if forcing his voice out.

Mr. Sakata went back into the city again on August 8. When he was in the Fujimi-cho area (now part of Naka Ward), a military policeman asked him to help remove corpses that were collapsed in a drain channel. He helped move about 10 bodies by carrying them on a stretcher to a truck, but the smell made him ill and he could not continue.

Desperate to go home, he was finally able to get a train ticket on August 13 and traveled to Shiwachi Station on the Geibi Line. Then he walked two hours to get home. “You’re alive!” Mr. Sakata’s grandfather, Zenshiro, said. His grandfather, his grandmother, Kikuno, and his mother, Yoshie, were all stunned to see that he had made it back. Zenshiro was like a father to Mr. Sakata after his father had died of disease. Every time the family saw a carriage or a two-wheel handcart going by the house, they had checked to see if it was Mr. Sakata.

Mr. Sakata had a low fever for several days, and his hair fell out. His family made him drink “doburoku” (unrefined sake) to aid his recuperation because they heard this would help cure him. It might have worked, as he was able to regain his health. It turned out that his uncle was also safe, having moved to a hospital in Togouchi-cho (now part of Akiota-cho) in June of that year.

Mr. Sakata graduated from Shudo Junior High School in the spring of 1946. Believing in the importance of good food, he worked for a local branch of the Japan Agricultural Cooperative, making efforts to increase food production. He even served as the president of the prefecture’s rural youth club. In the days before telephone, he developed and introduced a wired network through which households in the village could talk to one another.

In 2004, after he retired, Mr. Sakata established a non-profit organization to award a scholarship, which was the cherished desire of his late uncle. “I want to make the community a better place so young people can live safely in peace,” he said with determination. He has been speaking about his A-bomb experience at local schools since the 1970s. In 2014, he traveled around the world on a Peace Boat voyage, sharing his account. “This experience convinced me that people understand my antiwar spirit, even if there’s a language barrier,” he said.

The new imperial era of “Reiwa” has just begun. Based on his childhood experience, when people were led astray by the warmongering government and media, he said, “Knowing the truth and thinking for yourself is the cornerstone of peace. I hope there will be no war in the new era.”

Teenagers’ Impressions

I realized that time with my family is precious

The most shocking thing about Mr. Sakata’s story was that he and his family had no way of checking on each other’s safety until he got home a week after the atomic bombing. Now we have cell phones and I can reach my family at any time. I can’t imagine how anxious he was at that time. I realized that I mustn’t take for granted the peaceful life I now live with my family. (Ayu Hayashida, 14)

Each one of us is called upon to act

“Think about how long this peaceful life will last,” Mr. Sakata said, setting off an alarm bell in my head. He stressed to us the importance of thinking and deciding for ourselves even if we’re in the age of artificial intelligence (AI) and the Internet. I was so moved by the words of a person who had seen life and death in the war and the atomic bombing. We have to take responsibility for making a world without conflict; we can’t count on others to do it for us. Each one of us is called upon to act. (Anna Ikeda, 17)

(Originally published on May 6, 2019)

Takanari Sakata, 89, can never forget the dreadful sights he saw as he wandered through the city of Hiroshima in the aftermath of the atomic bombing. There were scores of bodies strewn everywhere. “I was lucky that I didn’t die, too,” he said. His gratitude for having survived has been a motivating force in his efforts to make the city of Miyoshi, his hometown, a positive place to live.

Mr. Sakata left his home in the village of Itaki in Hiroshima Prefecture (now part of Miwa-cho, Miyoshi City) to enter Shudo Junior High School in Hiroshima. He was 15 years old, in his fourth year of junior high school, when he experienced the atomic bombing while at the Hiroshima Shipyard of Mitsubishi Heavy Industries in Ebamachi (now part of Naka Ward), located about 3.7 kilometers from the hypocenter. At the time, he was mobilized for the war effort and was helping to install equipment on transport ships. He commuted by ferry from Miyajima, where his dormitory was located.

On the morning of August 6, 1945, he was at the Hiroshima Shipyard plant. The morning assembly had just finished when a blinding flash poured through the window. About 10 seconds later, his body was shaken by the bomb blast and he dove to the floor. Though his neck was cut by a piece of falling slate, he escaped serious injury.

He headed to the plant’s infirmary, thinking, “Maybe an armory in the city exploded.” There was blood all over the infirmary because pieces of glass had pierced the factory workers and nurses. The sky was glowing red, with a huge bud-shaped cloud rising in the sky. The factory workers were dragging their feet as they walked under the cloud. Mr. Sakata was dismayed and he waited for a ferry until that evening to return to his dormitory.

On the following day, August 7, Mr. Sakata went back into the city to look for his uncle, who had begun a new post at the Hiroshima Army Hospital. Injured people approached him, pleading for water, but he was unable to help them. He glanced to one side and saw a pile of bodies being cremated, but he went on walking. “It’s impossible to put that terrible scene into words,” Mr. Sakata said, as if forcing his voice out.

Mr. Sakata went back into the city again on August 8. When he was in the Fujimi-cho area (now part of Naka Ward), a military policeman asked him to help remove corpses that were collapsed in a drain channel. He helped move about 10 bodies by carrying them on a stretcher to a truck, but the smell made him ill and he could not continue.

Desperate to go home, he was finally able to get a train ticket on August 13 and traveled to Shiwachi Station on the Geibi Line. Then he walked two hours to get home. “You’re alive!” Mr. Sakata’s grandfather, Zenshiro, said. His grandfather, his grandmother, Kikuno, and his mother, Yoshie, were all stunned to see that he had made it back. Zenshiro was like a father to Mr. Sakata after his father had died of disease. Every time the family saw a carriage or a two-wheel handcart going by the house, they had checked to see if it was Mr. Sakata.

Mr. Sakata had a low fever for several days, and his hair fell out. His family made him drink “doburoku” (unrefined sake) to aid his recuperation because they heard this would help cure him. It might have worked, as he was able to regain his health. It turned out that his uncle was also safe, having moved to a hospital in Togouchi-cho (now part of Akiota-cho) in June of that year.

Mr. Sakata graduated from Shudo Junior High School in the spring of 1946. Believing in the importance of good food, he worked for a local branch of the Japan Agricultural Cooperative, making efforts to increase food production. He even served as the president of the prefecture’s rural youth club. In the days before telephone, he developed and introduced a wired network through which households in the village could talk to one another.

In 2004, after he retired, Mr. Sakata established a non-profit organization to award a scholarship, which was the cherished desire of his late uncle. “I want to make the community a better place so young people can live safely in peace,” he said with determination. He has been speaking about his A-bomb experience at local schools since the 1970s. In 2014, he traveled around the world on a Peace Boat voyage, sharing his account. “This experience convinced me that people understand my antiwar spirit, even if there’s a language barrier,” he said.

The new imperial era of “Reiwa” has just begun. Based on his childhood experience, when people were led astray by the warmongering government and media, he said, “Knowing the truth and thinking for yourself is the cornerstone of peace. I hope there will be no war in the new era.”

Teenagers’ Impressions

I realized that time with my family is precious

The most shocking thing about Mr. Sakata’s story was that he and his family had no way of checking on each other’s safety until he got home a week after the atomic bombing. Now we have cell phones and I can reach my family at any time. I can’t imagine how anxious he was at that time. I realized that I mustn’t take for granted the peaceful life I now live with my family. (Ayu Hayashida, 14)

Each one of us is called upon to act

“Think about how long this peaceful life will last,” Mr. Sakata said, setting off an alarm bell in my head. He stressed to us the importance of thinking and deciding for ourselves even if we’re in the age of artificial intelligence (AI) and the Internet. I was so moved by the words of a person who had seen life and death in the war and the atomic bombing. We have to take responsibility for making a world without conflict; we can’t count on others to do it for us. Each one of us is called upon to act. (Anna Ikeda, 17)

(Originally published on May 6, 2019)