Survivors’ Stories: Ai Masuda, 89, Hiroshima: Still haunted by horrific sights

Jul. 1, 2019

by Miho Kuwajima, Staff Writer

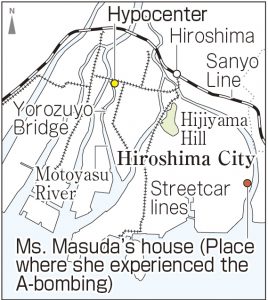

Last month, Ai Masuda (née Kimura), 89, stood at the foot of the Yorozuyo Bridge in Naka Ward, Hiroshima, and said, looking at the Motoyasu River, “Harue, I’m sorry I was unable to find you.” It was the first time she had returned to this place since searching for her cousin Harue, then 13 years old, in August 1945, 74 years ago.

Back then, Ms. Masuda was 15 years old and a fourth-year student at Hiroshima First Municipal Girls’ School (now Funairi High School). Her family was large, with 20 people, including her grandmother and the families of her father’s two brothers who lived in their house in Niho-cho (now part of Minami Ward). They sold coal and produced soy sauce for a living. The cousins grew up like siblings, and Harue, especially, who had just entered Hiroshima First Municipal Girls’ School, was like a sister to Ms. Masuda.

Because the munitions factory where she had been mobilized to work was closed on August 6, Ms. Masuda was at home that day and sewing a dress for Harue. Suddenly she saw a flash, and as she was wondering what happened, there was a tremendous boom.

Ms. Masuda was about five kilometers from the hypocenter. When she rushed out of the house and gazed toward the city center, she saw a huge cloud rising in the sky. Her uncle, who had gone to City Hall, came back in the afternoon and was covered in blood. However, Harue, who had headed to her work site in Zaimoku-cho (now part of Naka Ward) to help tear down homes to create a fire lane in the event of air raids, did not return home. In the early morning of August 8, Ms. Masuda went out to look for her with her mother and neighbors.

After visiting a friend of Harue’s in Danbara-cho (now part of Minami Ward) and asking where Harue had been, they headed for the city center, walking along the river. Victims of the bombing, their bodies red from the burns they suffered, were floating in the river near Hijiyama Hill. The body of a two- or three-year-old boy, still in a seated position, had maggots infested in his nostrils.

When they reached the west end of the Yorozuyo Bridge in Kako-machi (now part of Naka Ward), they came upon rotting male bodies with their intestines spilled out and the charred corpses of female students still standing upright. Looking back on those days, Ms. Masuda said, “Everyone died such a cruel death. I found myself gazing at scenes from hell.”

Until the evening of that day, they checked the first-aid stations that had sprung up in the city for the wounded. The classrooms and hallways of Koi National School (now Koi Elementary School) were so crowded with the injured and the dead that there was no place to step, and bodies were piled up as far as 50 meters ahead in front of a military hospital (now Hiroshima Prefectural Hospital) in Ujina-cho (now part of Minami Ward).

Harue’s remains were never found. It is believed that she lost her life, groaning in pain amid the fierce flames, along with 540 first- and second-year students from Hiroshima First Municipal Girls’ School who had been mobilized for the war effort. The publication entitled Floating Lanterns, published by Hiroshima First Municipal Girls’ School after the war to commemorate the dead, includes the account of one student who eluded instant death and said to her mother on her deathbed, “Everyone’s eyeballs popped from their sockets and their hair and clothes were burned. They were all crying, ‘Mother, help me,’ ‘Father, help me,’ or ‘Teacher, help me.’”

Hiroshima First Municipal Girls’ School lost a total of 666 students and ten teachers in the A-bomb attack. When the school reopened in October 1945, the teachers’ room in the main building, which had survived the bomb’s massive blast, was divided by a curtain and the students took two classes. After she graduated, Ms. Masuda helped out with the family business for several years and married Masao Masuda, now 92, when she was 24 years old. They had three children together.

Ms. Masuda longed for Harue, but she had no time to dwell on her experience of the bombing while busy with farm work, to help her mother-in-law, and with her children. The sight of dead bodies strewn everywhere had been deeply seared in her mind, and when she would walk through Peace Memorial Park, she sometimes felt sick. She said, “I tried to stay away from the park as much as I could.”

Prior to turning 90, Ms. Masuda was advised by a friend, whom she met again at an alumni reunion this spring, to write down her A-bomb experience, and she did so, on letter paper, for the first time. “Many young people, who were working hard and had no luxuries, became victims of the war. If they had survived, I think they would have lived a variety of lives,” she said. “I hope there will be lasting peace without war.” This is her message for the next generation.

Teenagers’ Impressions

Traumatized by her A-bomb experience at the age of 15

Ms. Masuda saw many dead bodies, including boys and girls still in a standing position, and told us, “They were scenes from hell.” She endured a horrific experience at the age of 15, and I think the pain she experienced has never really healed. I want to tell many others about this through social media or peace activities and convey her appeal for peace: “Our suffering should never again be experienced by anyone.” (Haruka Oikawa, 16)

Future of 666 students was stolen away

With the war intensifying, English was no longer taught at Hiroshima First Municipal Girls’ School, and the school was turned into a factory where military uniforms were made. Everyone believed that “Japan is winning the war,” and yet the school lost 666 students in the atomic bombing. As I listened to Ms. Masuda, I realized that the future of young people who were around the same age as I am now was suddenly stolen away. I want to continue doing what I can to help promote nuclear abolition and peace. (Kotoori Kawagishi, 16)

“Why did Harue have to die?”

Ms. Masuda lost her cousin Harue, who she was closest to, because of the atomic bomb. She still thinks, “Why did Harue have to die?” Why are innocent people’s precious lives stolen away? We have to convey the message that war must not be waged so no one will face the sort of suffering that Ms. Masuda has experienced. (Chihiro Tawara, 13)

(Originally published on July 1, 2019)

Last month, Ai Masuda (née Kimura), 89, stood at the foot of the Yorozuyo Bridge in Naka Ward, Hiroshima, and said, looking at the Motoyasu River, “Harue, I’m sorry I was unable to find you.” It was the first time she had returned to this place since searching for her cousin Harue, then 13 years old, in August 1945, 74 years ago.

Back then, Ms. Masuda was 15 years old and a fourth-year student at Hiroshima First Municipal Girls’ School (now Funairi High School). Her family was large, with 20 people, including her grandmother and the families of her father’s two brothers who lived in their house in Niho-cho (now part of Minami Ward). They sold coal and produced soy sauce for a living. The cousins grew up like siblings, and Harue, especially, who had just entered Hiroshima First Municipal Girls’ School, was like a sister to Ms. Masuda.

Because the munitions factory where she had been mobilized to work was closed on August 6, Ms. Masuda was at home that day and sewing a dress for Harue. Suddenly she saw a flash, and as she was wondering what happened, there was a tremendous boom.

Ms. Masuda was about five kilometers from the hypocenter. When she rushed out of the house and gazed toward the city center, she saw a huge cloud rising in the sky. Her uncle, who had gone to City Hall, came back in the afternoon and was covered in blood. However, Harue, who had headed to her work site in Zaimoku-cho (now part of Naka Ward) to help tear down homes to create a fire lane in the event of air raids, did not return home. In the early morning of August 8, Ms. Masuda went out to look for her with her mother and neighbors.

After visiting a friend of Harue’s in Danbara-cho (now part of Minami Ward) and asking where Harue had been, they headed for the city center, walking along the river. Victims of the bombing, their bodies red from the burns they suffered, were floating in the river near Hijiyama Hill. The body of a two- or three-year-old boy, still in a seated position, had maggots infested in his nostrils.

When they reached the west end of the Yorozuyo Bridge in Kako-machi (now part of Naka Ward), they came upon rotting male bodies with their intestines spilled out and the charred corpses of female students still standing upright. Looking back on those days, Ms. Masuda said, “Everyone died such a cruel death. I found myself gazing at scenes from hell.”

Until the evening of that day, they checked the first-aid stations that had sprung up in the city for the wounded. The classrooms and hallways of Koi National School (now Koi Elementary School) were so crowded with the injured and the dead that there was no place to step, and bodies were piled up as far as 50 meters ahead in front of a military hospital (now Hiroshima Prefectural Hospital) in Ujina-cho (now part of Minami Ward).

Harue’s remains were never found. It is believed that she lost her life, groaning in pain amid the fierce flames, along with 540 first- and second-year students from Hiroshima First Municipal Girls’ School who had been mobilized for the war effort. The publication entitled Floating Lanterns, published by Hiroshima First Municipal Girls’ School after the war to commemorate the dead, includes the account of one student who eluded instant death and said to her mother on her deathbed, “Everyone’s eyeballs popped from their sockets and their hair and clothes were burned. They were all crying, ‘Mother, help me,’ ‘Father, help me,’ or ‘Teacher, help me.’”

Hiroshima First Municipal Girls’ School lost a total of 666 students and ten teachers in the A-bomb attack. When the school reopened in October 1945, the teachers’ room in the main building, which had survived the bomb’s massive blast, was divided by a curtain and the students took two classes. After she graduated, Ms. Masuda helped out with the family business for several years and married Masao Masuda, now 92, when she was 24 years old. They had three children together.

Ms. Masuda longed for Harue, but she had no time to dwell on her experience of the bombing while busy with farm work, to help her mother-in-law, and with her children. The sight of dead bodies strewn everywhere had been deeply seared in her mind, and when she would walk through Peace Memorial Park, she sometimes felt sick. She said, “I tried to stay away from the park as much as I could.”

Prior to turning 90, Ms. Masuda was advised by a friend, whom she met again at an alumni reunion this spring, to write down her A-bomb experience, and she did so, on letter paper, for the first time. “Many young people, who were working hard and had no luxuries, became victims of the war. If they had survived, I think they would have lived a variety of lives,” she said. “I hope there will be lasting peace without war.” This is her message for the next generation.

Teenagers’ Impressions

Traumatized by her A-bomb experience at the age of 15

Ms. Masuda saw many dead bodies, including boys and girls still in a standing position, and told us, “They were scenes from hell.” She endured a horrific experience at the age of 15, and I think the pain she experienced has never really healed. I want to tell many others about this through social media or peace activities and convey her appeal for peace: “Our suffering should never again be experienced by anyone.” (Haruka Oikawa, 16)

Future of 666 students was stolen away

With the war intensifying, English was no longer taught at Hiroshima First Municipal Girls’ School, and the school was turned into a factory where military uniforms were made. Everyone believed that “Japan is winning the war,” and yet the school lost 666 students in the atomic bombing. As I listened to Ms. Masuda, I realized that the future of young people who were around the same age as I am now was suddenly stolen away. I want to continue doing what I can to help promote nuclear abolition and peace. (Kotoori Kawagishi, 16)

“Why did Harue have to die?”

Ms. Masuda lost her cousin Harue, who she was closest to, because of the atomic bomb. She still thinks, “Why did Harue have to die?” Why are innocent people’s precious lives stolen away? We have to convey the message that war must not be waged so no one will face the sort of suffering that Ms. Masuda has experienced. (Chihiro Tawara, 13)

(Originally published on July 1, 2019)