Striving to fill voids in Hiroshima, Part 10: Documents of establishments in the air

Dec. 11, 2019

by Kyosuke Mizukawa, Staff Writer

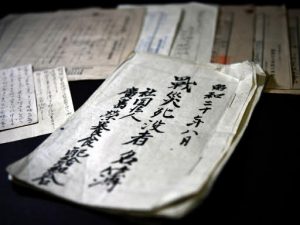

Register of A-bomb victims made by 29 establishments

Among the “Union Documents on Hiroshima Prefecture Nutritional Foods Distribution,” a collection held at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, there is a list of names of 323 people who died as a result of the atomic bombing. They were workers who belonged to 29 establishments in the city of Hiroshima, including an ironworks, a screw factory, and a woodworking shop. The documents were donated to the museum in 2005 by the family of the late Keitaro Kambara, the managing director of the Hiroshima Prefecture Nutritional Foods Distribution during the war years.

Valuable source of information

The union used to distribute meals to its investors and members, but was forced to dissolve the organization due to the catastrophic damage it suffered from the atomic bombing on August 6, 1945. Having decided to allot part of its remaining property to provide perpetual services for the A-bomb victims, Mr. Kambara and other union staff members jointly placed an appeal in the Chugoku Shimbun on January 24, 1946, asking investors and union members to inform them of the names of their family members or business partners who lost their lives because of the atomic bomb.

“Out of friendship and connections by eating from the same bowl, we would like to pray perpetually for the souls of those who tragically departed this life...”

As I turned the pages of the report from the “statistical survey of atomic bomb victims” that was compiled by the City of Hiroshima, which has been steadily obtaining names of the A-bomb victims, it became clear that for this survey the city made use of company histories that had been published by such businesses as Hiroshima Bank and Fukuya Department Store. In that sense, the lists compiled by businesses are indeed valuable sources of information.

However, there are no references to such lists after fiscal 1990, even when new information has become available. For example, Hiroshima Shinkin Bank (formerly, the Hiroshima City Credit Cooperative) deposited its register containing the names of 48 victims with the Hiroshima Prefectural Archives, in Naka Ward, in March of this year. It is the same list that appeared in a book recounting the history of the bank that was issued in 1996.

According to the city, the Peace Promotion Division, which keeps the running list of victims, is, in principle, responsible for updates when an old list is found or donated. The information is then shared with the Atomic Bomb Survivors Relief Department, which conducts the statistical survey. If a list is submitted elsewhere, like the Peace Memorial Museum, they are required to go through the same procedure to utilize the information. However, there are no specific rules to follow.

After the city initiated the survey in 1979, city staff members met regularly with Hiroshima University and other relevant organizations to share information, but no meetings have been held since fiscal 1999. One reason is that checking names to avoid duplication has become a key concern as more and more materials are obtained, and they are unable to focus their efforts on finding new names.

Satoru Ubuki, a former professor at Hiroshima Jogakuin University, urges the city to work together urgently with related bodies not only to collect further information but also to prevent the materials it has already used from being scattered and lost. He said, “There is a limit to what the City of Hiroshima can do by itself. The key is what kind of support the city can receive from the national government, the prefectural government, and other local governments.”

Shuichi Kato, the deputy director of the museum, said, “We can’t determine whether donated lists are useful for the survey.” On the other hand, he pins his hopes on the “Union Documents on Hiroshima Prefecture Nutritional Foods Distribution” due to its detailed record, saying that he would consider promoting the exchange of information with the Atomic Bomb Survivors Relief Department and the Hiroshima University Research Institute for Radiation Biology and Medicine (RIRBM, in Minami Ward), which helps the city with the survey.

“I’m sure my grandfather would be happy.”

The words “died on August 6 during the war,” or “killed at a factory” can be read in the letters and cards sent from union members who responded to the appeal for information, made by Mr. Kambara. This information is not limited to names. The date and place of death, or the age of the victim, are also included in these letters. “We deeply regret that we have to give up our business,” Mr. Kambara announced to members in the appeal. He himself was buried under the collapsed union building about two kilometers from the hypocenter and suffered severe injuries, yet completed the list.

Mr. Kambara’s granddaughter, Sachiyo, 62, a resident of Fukuyama City, readily consented to my request to consult the list, stressing, “I’m sure my grandfather would be happy if it can be used to identify the victims.”

(Originally published on December 11, 2019)

Register of A-bomb victims made by 29 establishments

Among the “Union Documents on Hiroshima Prefecture Nutritional Foods Distribution,” a collection held at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, there is a list of names of 323 people who died as a result of the atomic bombing. They were workers who belonged to 29 establishments in the city of Hiroshima, including an ironworks, a screw factory, and a woodworking shop. The documents were donated to the museum in 2005 by the family of the late Keitaro Kambara, the managing director of the Hiroshima Prefecture Nutritional Foods Distribution during the war years.

Valuable source of information

The union used to distribute meals to its investors and members, but was forced to dissolve the organization due to the catastrophic damage it suffered from the atomic bombing on August 6, 1945. Having decided to allot part of its remaining property to provide perpetual services for the A-bomb victims, Mr. Kambara and other union staff members jointly placed an appeal in the Chugoku Shimbun on January 24, 1946, asking investors and union members to inform them of the names of their family members or business partners who lost their lives because of the atomic bomb.

“Out of friendship and connections by eating from the same bowl, we would like to pray perpetually for the souls of those who tragically departed this life...”

As I turned the pages of the report from the “statistical survey of atomic bomb victims” that was compiled by the City of Hiroshima, which has been steadily obtaining names of the A-bomb victims, it became clear that for this survey the city made use of company histories that had been published by such businesses as Hiroshima Bank and Fukuya Department Store. In that sense, the lists compiled by businesses are indeed valuable sources of information.

However, there are no references to such lists after fiscal 1990, even when new information has become available. For example, Hiroshima Shinkin Bank (formerly, the Hiroshima City Credit Cooperative) deposited its register containing the names of 48 victims with the Hiroshima Prefectural Archives, in Naka Ward, in March of this year. It is the same list that appeared in a book recounting the history of the bank that was issued in 1996.

According to the city, the Peace Promotion Division, which keeps the running list of victims, is, in principle, responsible for updates when an old list is found or donated. The information is then shared with the Atomic Bomb Survivors Relief Department, which conducts the statistical survey. If a list is submitted elsewhere, like the Peace Memorial Museum, they are required to go through the same procedure to utilize the information. However, there are no specific rules to follow.

After the city initiated the survey in 1979, city staff members met regularly with Hiroshima University and other relevant organizations to share information, but no meetings have been held since fiscal 1999. One reason is that checking names to avoid duplication has become a key concern as more and more materials are obtained, and they are unable to focus their efforts on finding new names.

Satoru Ubuki, a former professor at Hiroshima Jogakuin University, urges the city to work together urgently with related bodies not only to collect further information but also to prevent the materials it has already used from being scattered and lost. He said, “There is a limit to what the City of Hiroshima can do by itself. The key is what kind of support the city can receive from the national government, the prefectural government, and other local governments.”

Shuichi Kato, the deputy director of the museum, said, “We can’t determine whether donated lists are useful for the survey.” On the other hand, he pins his hopes on the “Union Documents on Hiroshima Prefecture Nutritional Foods Distribution” due to its detailed record, saying that he would consider promoting the exchange of information with the Atomic Bomb Survivors Relief Department and the Hiroshima University Research Institute for Radiation Biology and Medicine (RIRBM, in Minami Ward), which helps the city with the survey.

“I’m sure my grandfather would be happy.”

The words “died on August 6 during the war,” or “killed at a factory” can be read in the letters and cards sent from union members who responded to the appeal for information, made by Mr. Kambara. This information is not limited to names. The date and place of death, or the age of the victim, are also included in these letters. “We deeply regret that we have to give up our business,” Mr. Kambara announced to members in the appeal. He himself was buried under the collapsed union building about two kilometers from the hypocenter and suffered severe injuries, yet completed the list.

Mr. Kambara’s granddaughter, Sachiyo, 62, a resident of Fukuyama City, readily consented to my request to consult the list, stressing, “I’m sure my grandfather would be happy if it can be used to identify the victims.”

(Originally published on December 11, 2019)