Striving to fill voids in Hiroshima 75 years after the atomic bombing—Remains of victims wait to be claimed by family

Feb. 3, 2020

by Yuji Yamamoto, Staff Writer

Remains found at various places moved to Atomic Bomb Memorial Mound

On August 6, 1945, a single atomic bomb was dropped from the skies above Hiroshima by the U.S. military. Many were killed instantly or died of wounds at schools or temples, which were being used as temporary aid stations. Countless bodies were cremated on playgrounds or riverbanks, but many remains are enshrined at places in and around the city of Hiroshima, not yet being “reunited” with family. Unidentified remains have repeatedly been excavated from numerous mass burial sites. We hope to consider the catastrophic damage caused by the atomic bombing from the significance of the bone fragments of each person who had lived until that day.

Large number of unidentified remains indicate chaos in devastated Hiroshima

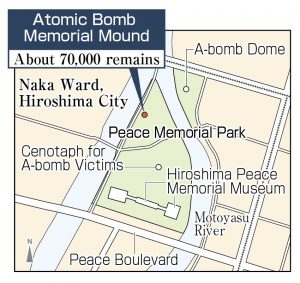

The Atomic Bomb Memorial Mound, in Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park (Naka Ward, Hiroshima City), is a mound of soil measuring 16 meters in diameter and 3.5 meters in height with an underground vault. Compared to the Cenotaph for the A-bomb Victims in the center of the park, with its register of A-bomb victims’ names, few visitors make it to the Atomic Bomb Memorial Mound.

The remains of about 70,000 A-bomb victims are at rest within the memorial mound, a testament to the chaos and tragedy of the devastation of Hiroshima.

Immediately after the atomic bombing, soldiers attached to a military unit serving in and around Hiroshima headed to join the rescue efforts. Keiji Tsuchiya, 91, city of Kasaoka, is one who went into the heart of the city. Mr. Tsuchiya was 17 at the time and entered Hiroshima from Konoura (now part of Etajima city), where he was undergoing training for a naval suicide attack mission.

Mr. Tsuchiya immersed himself in a river and began pulling out bodies that covered the water’s surface, carrying them to makeshift crematories. Some days 60 to 70 people were cremated. Mr. Tsuchiya said he wrote down the names and addresses indicated on name tags attached to clothes. But, he added, there was no identifying information available for the charred bodies.

The remains of those with known names were handed to family members at Hiroshima City Hall, but there were many more with no identity. Such remains were delivered to Zenpoji Temple in the town of Koi (now part of Nishi Ward) at the end of 1945. Many other remains were brought to the site of the Jisenji Temple in Nakajima Honmachi, the area that is now Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park. These remains were transferred to the Memorial Monument for the War Victims, which was built in 1946 with a chapel and a temporary vault by the Hiroshima Society for Praying for the War Dead (predecessor of the present-day Hiroshima Society for Praying for the War Victims).

When today’s Atomic Bomb Memorial Mound was created in 1955 to replace the Memorial Monument for the War Victims, many remains of A-bomb victims kept at various locations were brought there and placed in the memorial mound’s underground vault. Among them were remains found on Ninoshima Island (now part of Minami Ward), where around 10,000 wounded were taken after the atomic bombing. Since then, remains discovered at construction sites or by excavation work initiated using clues to whereabouts have been delivered to the Atomic Bomb Memorial Mound.

In Hiroshima, about 7,200 mobilized students lost their lives in the atomic bombing while engaged in housing demolition work to create fire lanes in the central part of the city. Many families were never able to find their children, who had gone missing after the atomic bombing. Now understood is the reality that Japan persisted in war by mobilizing even children.

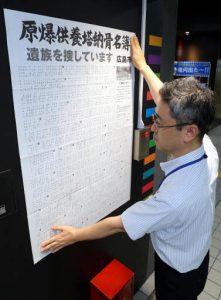

Although only a small portion of the 70,000, some remains with names rest in the underground vault. When the city government of Hiroshima first made public a list of unclaimed remains held in the memorial mound in 1968, there were 2,355 names. The city started sending the list of remains to local governments across Japan in 1975. The late Toshiko Saeki, who lost 13 relatives in the atomic bombing, was committed to finding family members of the deceased even as she worked daily to clean the Atomic Bomb Memorial Mound. Despite such efforts, there are still 814 remains unclaimed by family.

“We will keep looking for the families of those whose names have been identified and continue holding a memorial service for those whose names are unknown,” said Minoru Hataguchi, 73, president of the Hiroshima Society for Praying for the War Victims. “I think the mound could also serve as something like a gravesite for people to come and pray.”

The Atomic Bomb Memorial Mound is believed by surviving families to be a place where their beloved have been laid to rest and where they can “reunite” with them. In the morning on the 6th of every month, Nobuharu Kikkawa, 83, chief priest of the Hakurenji Temple in the city of Kure, travels to Hiroshima from his home in Kure to chant sutras in front of the memorial mound. He has done so for about 60 years, following in his parents’ footsteps.

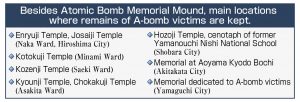

Because Hiroshima’s city functions were completely destroyed at that time, and the number of the wounded overwhelming, first-aid stations were set up across an extensive area. Not only in the Atomic Bomb Memorial Mound, unclaimed remains have been held widely, even in temples located far away in the northern part of Hiroshima prefecture. In 1973, the remains of more than 13 soldiers killed in the atomic bombing were excavated from the site of a former military hospital in Era in the city of Yamaguchi. The remains were later moved to a memorial dedicated to the A-bomb victims built by Yuda-en, a welfare center for A-bomb survivors in the prefecture of Yamaguchi.

Uncertain evidence for 70,000

Estimates are that the remains of 70,000 victims are held in the Atomic Bomb Memorial Mound, with Hiroshima City using that number as an official count. And yet, no solid evidence exists to support this number.

According to Hiroshima Society records, remains of A-bomb victims kept in various locations, including the burial mound on Ninoshima Island (about 2,000), Zenpoji Temple (about 500), and the former Memorial Monument for the War Victims (about 50,000), were transported to the Atomic Bomb Memorial Mound when it was completed in 1955. Chugoku Shimbun, while conscious of the fact that the number was an estimate, had used “about 50,000” in its articles until 1976, when it began to use 70,000.

In the same year, the city governments of Hiroshima and Nagasaki submitted a request to the United Nations. The request estimated there to be a total of “140,000 (plus-minus 10,000)” A-bomb victims in Hiroshima who had died by the end of 1945. In the meantime, a report compiled by the former Hiroshima Prefectural Police Department at the end of November 1945 indicated that autopsies had been conducted on “78,150” victims. This number was also referred to in the 1967 Report of the U.N. Secretary-General. The result of simple subtraction using the two figures comes out to be between 50,000 and more than 70,000.

The number 70,000 began to be used commonly in the 1970s, when many bodies exhumed on Ninoshima Island (Minami Ward) and remains enshrined at different temples over a long time period were transported to the Atomic Bomb Memorial Mound, adding these remains numbers to the 50,000 victims who were already at rest in the mound.

In any case, as there is no solid evidence, proving these numbers is difficult. With so many unidentified bodies, we can only estimate the number of A-bomb victims. This “void” of the extent of actual damage perfectly illustrates the inhumanity of nuclear weapons.

(Originally published on February 3, 2020)

Remains found at various places moved to Atomic Bomb Memorial Mound

On August 6, 1945, a single atomic bomb was dropped from the skies above Hiroshima by the U.S. military. Many were killed instantly or died of wounds at schools or temples, which were being used as temporary aid stations. Countless bodies were cremated on playgrounds or riverbanks, but many remains are enshrined at places in and around the city of Hiroshima, not yet being “reunited” with family. Unidentified remains have repeatedly been excavated from numerous mass burial sites. We hope to consider the catastrophic damage caused by the atomic bombing from the significance of the bone fragments of each person who had lived until that day.

Large number of unidentified remains indicate chaos in devastated Hiroshima

The Atomic Bomb Memorial Mound, in Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park (Naka Ward, Hiroshima City), is a mound of soil measuring 16 meters in diameter and 3.5 meters in height with an underground vault. Compared to the Cenotaph for the A-bomb Victims in the center of the park, with its register of A-bomb victims’ names, few visitors make it to the Atomic Bomb Memorial Mound.

The remains of about 70,000 A-bomb victims are at rest within the memorial mound, a testament to the chaos and tragedy of the devastation of Hiroshima.

Immediately after the atomic bombing, soldiers attached to a military unit serving in and around Hiroshima headed to join the rescue efforts. Keiji Tsuchiya, 91, city of Kasaoka, is one who went into the heart of the city. Mr. Tsuchiya was 17 at the time and entered Hiroshima from Konoura (now part of Etajima city), where he was undergoing training for a naval suicide attack mission.

Mr. Tsuchiya immersed himself in a river and began pulling out bodies that covered the water’s surface, carrying them to makeshift crematories. Some days 60 to 70 people were cremated. Mr. Tsuchiya said he wrote down the names and addresses indicated on name tags attached to clothes. But, he added, there was no identifying information available for the charred bodies.

The remains of those with known names were handed to family members at Hiroshima City Hall, but there were many more with no identity. Such remains were delivered to Zenpoji Temple in the town of Koi (now part of Nishi Ward) at the end of 1945. Many other remains were brought to the site of the Jisenji Temple in Nakajima Honmachi, the area that is now Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park. These remains were transferred to the Memorial Monument for the War Victims, which was built in 1946 with a chapel and a temporary vault by the Hiroshima Society for Praying for the War Dead (predecessor of the present-day Hiroshima Society for Praying for the War Victims).

When today’s Atomic Bomb Memorial Mound was created in 1955 to replace the Memorial Monument for the War Victims, many remains of A-bomb victims kept at various locations were brought there and placed in the memorial mound’s underground vault. Among them were remains found on Ninoshima Island (now part of Minami Ward), where around 10,000 wounded were taken after the atomic bombing. Since then, remains discovered at construction sites or by excavation work initiated using clues to whereabouts have been delivered to the Atomic Bomb Memorial Mound.

In Hiroshima, about 7,200 mobilized students lost their lives in the atomic bombing while engaged in housing demolition work to create fire lanes in the central part of the city. Many families were never able to find their children, who had gone missing after the atomic bombing. Now understood is the reality that Japan persisted in war by mobilizing even children.

Although only a small portion of the 70,000, some remains with names rest in the underground vault. When the city government of Hiroshima first made public a list of unclaimed remains held in the memorial mound in 1968, there were 2,355 names. The city started sending the list of remains to local governments across Japan in 1975. The late Toshiko Saeki, who lost 13 relatives in the atomic bombing, was committed to finding family members of the deceased even as she worked daily to clean the Atomic Bomb Memorial Mound. Despite such efforts, there are still 814 remains unclaimed by family.

“We will keep looking for the families of those whose names have been identified and continue holding a memorial service for those whose names are unknown,” said Minoru Hataguchi, 73, president of the Hiroshima Society for Praying for the War Victims. “I think the mound could also serve as something like a gravesite for people to come and pray.”

The Atomic Bomb Memorial Mound is believed by surviving families to be a place where their beloved have been laid to rest and where they can “reunite” with them. In the morning on the 6th of every month, Nobuharu Kikkawa, 83, chief priest of the Hakurenji Temple in the city of Kure, travels to Hiroshima from his home in Kure to chant sutras in front of the memorial mound. He has done so for about 60 years, following in his parents’ footsteps.

Because Hiroshima’s city functions were completely destroyed at that time, and the number of the wounded overwhelming, first-aid stations were set up across an extensive area. Not only in the Atomic Bomb Memorial Mound, unclaimed remains have been held widely, even in temples located far away in the northern part of Hiroshima prefecture. In 1973, the remains of more than 13 soldiers killed in the atomic bombing were excavated from the site of a former military hospital in Era in the city of Yamaguchi. The remains were later moved to a memorial dedicated to the A-bomb victims built by Yuda-en, a welfare center for A-bomb survivors in the prefecture of Yamaguchi.

Uncertain evidence for 70,000

Estimates are that the remains of 70,000 victims are held in the Atomic Bomb Memorial Mound, with Hiroshima City using that number as an official count. And yet, no solid evidence exists to support this number.

According to Hiroshima Society records, remains of A-bomb victims kept in various locations, including the burial mound on Ninoshima Island (about 2,000), Zenpoji Temple (about 500), and the former Memorial Monument for the War Victims (about 50,000), were transported to the Atomic Bomb Memorial Mound when it was completed in 1955. Chugoku Shimbun, while conscious of the fact that the number was an estimate, had used “about 50,000” in its articles until 1976, when it began to use 70,000.

In the same year, the city governments of Hiroshima and Nagasaki submitted a request to the United Nations. The request estimated there to be a total of “140,000 (plus-minus 10,000)” A-bomb victims in Hiroshima who had died by the end of 1945. In the meantime, a report compiled by the former Hiroshima Prefectural Police Department at the end of November 1945 indicated that autopsies had been conducted on “78,150” victims. This number was also referred to in the 1967 Report of the U.N. Secretary-General. The result of simple subtraction using the two figures comes out to be between 50,000 and more than 70,000.

The number 70,000 began to be used commonly in the 1970s, when many bodies exhumed on Ninoshima Island (Minami Ward) and remains enshrined at different temples over a long time period were transported to the Atomic Bomb Memorial Mound, adding these remains numbers to the 50,000 victims who were already at rest in the mound.

In any case, as there is no solid evidence, proving these numbers is difficult. With so many unidentified bodies, we can only estimate the number of A-bomb victims. This “void” of the extent of actual damage perfectly illustrates the inhumanity of nuclear weapons.

(Originally published on February 3, 2020)