Striving to fill voids in Hiroshima 75 years after the atomic bombing—Unclaimed A-bomb victims’ remains, Part 11: Diary of a mother

Feb. 17, 2020

by Kyosuke Mizukawa and Yuji Yamamoto, Staff Writers

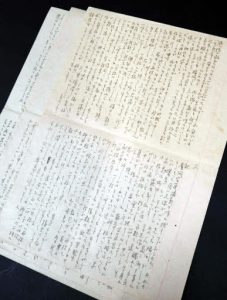

“Morio, where are you? All I want is to see you even if I have to walk through the flames.” Inside the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, in the city of Hiroshima’s Naka Ward, is held a handwritten diary of Matsuyo Mieno (who died in 1982 at age 82). She recorded days of walking around the scorched city in search of her 12-year-old son in the summer 75 years ago.

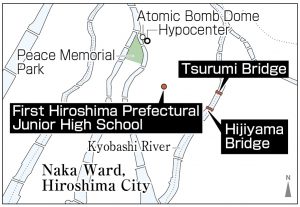

Morio, Matsuyo’s oldest son, was a first-year student at First Hiroshima Prefectural Junior High School (now Kokutaiji High School, Naka Ward). On the morning of August 6, 1945, he left home to help tear down houses near the school, where he was overcome by the thermal rays from the atomic bombing.

With a huge cloud rising from the city center into the sky, Matsuyo rushed out of her suburban home in the village of Inokuchi (now part of Nishi Ward) to look for Morio. When she made it to her son’s school, she found there were no traces of even the school building. Dead bodies of students were lying here and there. “Most were naked, badly burned, near death, or had already passed. I took a closer look at each of them, just about your age, but they were impossible to identify because of severe burns.”

On the evening of August 8, Matsuyo heard from an acquaintance that Morio was on the east side of Tsurumi Bridge. He had apparently collapsed with burns on his face and chest and had asked for water. She blamed herself because she had searched only as far as around Hijiyama Bridge, which was close to Tsurumi Bridge. “I am tormented by regret for not expanding my search a bit further to Tsurumi Bridge. My heart is torn to pieces. Morio, please forgive your mother. Take care of yourself.”

Conducted funeral by lighting sheet of Japanese writing paper

Later, she rushed to the Tsurumi Bridge but was told the wounded had already been picked up by the military. Matsuyo’s husband, Sadao, went to the islands of Ninoshima and Kanawajima off the coast of the city but could not find their son. On September 21, they held a funeral for him by burning a sheet of Japanese writing paper on which they had inscribed Morio’s name.

The diary, written by a mother whose words seemed to be wrung from her, was donated to the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum in 2004 by Morio’s sister, Yuri Chamoto, 90, resident of the city of Higashimurayama in Tokyo. At the time of the atomic bombing, Ms. Chamoto was a fourth-year student at First Hiroshima Prefectural Girls’ High School (now Minami High School). She was off from school that day and escaped the bombing. But 233 of her school’s first-year students, who had been mobilized to do the work of tearing down houses, were all killed.

Yuri’s father Sadao was in the navy, and the family had just moved to Hiroshima from the prefecture of Kanagawa in the spring of 1945. The family could not leave Hiroshima, “thinking that Morio might be somewhere.” They remained in the city, where they had no local ties, for more than 10 years after the war.

Every morning, Matsuyo offered water to a memorial portrait of Morio, who was said to have begged for water. “My brother always had a smile on his face and was loved by our parents. I would like people to know the grief of parents who never locate the remains of a child,” said his sister Ms. Chamoto.

“My parents searched hard for my sister, but she has not yet been found.” Toshiki Fujimori, 75, an A-bomb survivor who lives in the city of Chino in the prefecture of Nagano, lost his sister Toshiko in the atomic bombing. She was a 13-year-old first-year student at Hiroshima First Municipal Girls’ School (now Funairi High School) at that time. Her remains have yet to be found. At the municipal girls’ school, all 541 first- and second-year students, who were mobilized to demolish houses on the south side of the present-day Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park, were killed in the atomic bombing.

Bearing in mind the chagrin and anger of bereaved families of A-bomb victims, Mr. Fujimori, assistant secretary general of the Japan Confederation of A- and H-Bomb Sufferers Organizations (Nihon Hidankyo), has been telling the story of his sister to people around the world, stressing the “inhumanity of nuclear weapons.”

World needs to listen to voices of voiceless

While there are countless remains of unclaimed A-bomb victims whose ties to family and community were cut, some remains’ names have been identified. Although this number is small, bereaved family were located through the confirmation of certain kinds of documents, such as those kept at government offices or personal memoirs. At the same time, innumerable unidentified victims, including about 70,000 remains held in the Atomic Bomb Memorial Mound (Naka Ward), are the “void” reminding us of the fact that a single atomic bomb destroyed the city in an instant and incinerated humans to ash, making their identification impossible.

The nuclear weapons ban treaty, which recognizes nuclear weapons as “inhumane,” was realized in 2017, as Mr. Fujimori and other A-bomb survivors looked on at the United Nations. The world should listen closely to “the voices of the voiceless,” who rest in the Atomic Bomb Memorial Mound or have been buried underground in the city or on offshore islands after being stripped of their humanity.

(Originally published on February 17, 2020)

Continued search for children

Conveying “inhumanity” of nuclear weapons

“Morio, where are you? All I want is to see you even if I have to walk through the flames.” Inside the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, in the city of Hiroshima’s Naka Ward, is held a handwritten diary of Matsuyo Mieno (who died in 1982 at age 82). She recorded days of walking around the scorched city in search of her 12-year-old son in the summer 75 years ago.

Morio, Matsuyo’s oldest son, was a first-year student at First Hiroshima Prefectural Junior High School (now Kokutaiji High School, Naka Ward). On the morning of August 6, 1945, he left home to help tear down houses near the school, where he was overcome by the thermal rays from the atomic bombing.

With a huge cloud rising from the city center into the sky, Matsuyo rushed out of her suburban home in the village of Inokuchi (now part of Nishi Ward) to look for Morio. When she made it to her son’s school, she found there were no traces of even the school building. Dead bodies of students were lying here and there. “Most were naked, badly burned, near death, or had already passed. I took a closer look at each of them, just about your age, but they were impossible to identify because of severe burns.”

On the evening of August 8, Matsuyo heard from an acquaintance that Morio was on the east side of Tsurumi Bridge. He had apparently collapsed with burns on his face and chest and had asked for water. She blamed herself because she had searched only as far as around Hijiyama Bridge, which was close to Tsurumi Bridge. “I am tormented by regret for not expanding my search a bit further to Tsurumi Bridge. My heart is torn to pieces. Morio, please forgive your mother. Take care of yourself.”

Conducted funeral by lighting sheet of Japanese writing paper

Later, she rushed to the Tsurumi Bridge but was told the wounded had already been picked up by the military. Matsuyo’s husband, Sadao, went to the islands of Ninoshima and Kanawajima off the coast of the city but could not find their son. On September 21, they held a funeral for him by burning a sheet of Japanese writing paper on which they had inscribed Morio’s name.

The diary, written by a mother whose words seemed to be wrung from her, was donated to the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum in 2004 by Morio’s sister, Yuri Chamoto, 90, resident of the city of Higashimurayama in Tokyo. At the time of the atomic bombing, Ms. Chamoto was a fourth-year student at First Hiroshima Prefectural Girls’ High School (now Minami High School). She was off from school that day and escaped the bombing. But 233 of her school’s first-year students, who had been mobilized to do the work of tearing down houses, were all killed.

Yuri’s father Sadao was in the navy, and the family had just moved to Hiroshima from the prefecture of Kanagawa in the spring of 1945. The family could not leave Hiroshima, “thinking that Morio might be somewhere.” They remained in the city, where they had no local ties, for more than 10 years after the war.

Every morning, Matsuyo offered water to a memorial portrait of Morio, who was said to have begged for water. “My brother always had a smile on his face and was loved by our parents. I would like people to know the grief of parents who never locate the remains of a child,” said his sister Ms. Chamoto.

“My parents searched hard for my sister, but she has not yet been found.” Toshiki Fujimori, 75, an A-bomb survivor who lives in the city of Chino in the prefecture of Nagano, lost his sister Toshiko in the atomic bombing. She was a 13-year-old first-year student at Hiroshima First Municipal Girls’ School (now Funairi High School) at that time. Her remains have yet to be found. At the municipal girls’ school, all 541 first- and second-year students, who were mobilized to demolish houses on the south side of the present-day Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park, were killed in the atomic bombing.

Bearing in mind the chagrin and anger of bereaved families of A-bomb victims, Mr. Fujimori, assistant secretary general of the Japan Confederation of A- and H-Bomb Sufferers Organizations (Nihon Hidankyo), has been telling the story of his sister to people around the world, stressing the “inhumanity of nuclear weapons.”

World needs to listen to voices of voiceless

While there are countless remains of unclaimed A-bomb victims whose ties to family and community were cut, some remains’ names have been identified. Although this number is small, bereaved family were located through the confirmation of certain kinds of documents, such as those kept at government offices or personal memoirs. At the same time, innumerable unidentified victims, including about 70,000 remains held in the Atomic Bomb Memorial Mound (Naka Ward), are the “void” reminding us of the fact that a single atomic bomb destroyed the city in an instant and incinerated humans to ash, making their identification impossible.

The nuclear weapons ban treaty, which recognizes nuclear weapons as “inhumane,” was realized in 2017, as Mr. Fujimori and other A-bomb survivors looked on at the United Nations. The world should listen closely to “the voices of the voiceless,” who rest in the Atomic Bomb Memorial Mound or have been buried underground in the city or on offshore islands after being stripped of their humanity.

(Originally published on February 17, 2020)