Survivors’ Stories: Yachiyo Kato, 91, Nishi Ward, Hiroshima: I escaped death thanks to my teacher’s decision

Jun. 22, 2020

by Miho Kuwajima, Staff Writer

Yachiyo Kato (née Tominaga), now 91, who graduated from Hiroshima First Municipal Girls’ School (now Funairi High School), believes she was able to survive the atomic bombing thanks to a teacher’s decision. With the thought that she was allowed to survive A-bombing to convey her experience to young people, she has devoted half of her life to passing on the A-bomb accounts of students from Hiroshima First Municipal Girls’ School.

Ms. Kato entered the school in April 1941 and went on to the advanced course, which was established during the war in the spring of 1945. She was making machine-gun bullets as a mobilized student every day at the factory of the Japan Steel Works located in Nishikaniya-cho (now part of Minami Ward). August 6 fell on a day when the factory was closed once each month because of a shortage of electric power.

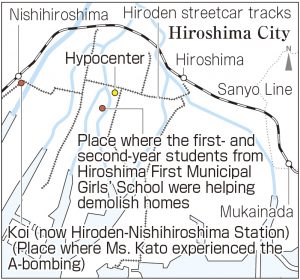

Ms. Kato had plans to go to the island of Miyajima with friends. She left her home, located in Mukainada-nakamachi (now part of Minami Ward), early in the morning, and when she was waiting for her friends in front of Koi Station (now Hiroden-Nishihiroshima Station) a little past eight, she was suddenly blown about 10 meters by the A-bomb blast and lost consciousness.

She was about 2.5 kilometers from the hypocenter, but she does not remember the bomb’s flash of light or its roar. When she came to, she found lunch boxes and wooden clogs scattered about, and students in a lower grade who were with her, had been injured from glass fragments piercing her cheeks and shoulders. She received first aid at Kusatsu National School (now Kusatsu Elementary School), which functioned as a temporary relief station, and headed to her home, avoiding fires.

On her way home, she was exposed to the black and thick rain and saw people whose skin hung down in strips, students nearly naked, and women with hair standing upright wherever she went. When she arrived at her home, it was past 8:00 p.m.

Two days later, a woman involved with a women’s group who took part in the rescue efforts at Aosaki National School (now Aosaki Elementary School) in the neighborhood, came to inform Ms. Kato that her classmate, Tsuneko Yoshimoto was staying there. Ms. Yoshimoto was one of Ms. Kato’s friends with whom she had planned to go to Miyajima. Ms. Yoshimoto was exposed to the atomic bomb on a streetcar when it was passing near the Dobashi streetcar stop, and then was carried there.

Ms. Kato decided to bring her to Ms. Kato’s home to take care of her until Ms. Yoshimoto’s mother came to get her. She laid her on the futon and tried to give her grated cucumber and crushed tomato, but she immediately threw it up. In retrospect, the inside of her mouth was bright yellow perhaps because of the effects of her radiation exposure. Several days later, Ms. Yoshimoto was brought back home in Midori-machi (now part of Minami Ward) on a two-wheel cart and passed away around August 24.

Hiroshima First Municipal Girls’ School lost a total of 676 people including ten teachers in the A-bomb attack. Five hundred forty one first- and second-year students were mobilized to demolish homes to create fire lanes south of what is now Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park in the city’s Naka Ward, were exposed to the A-bomb’s heat and blast around 500 meters from the hypocenter. All of them died. “Most students’ eyeballs had popped from their sockets and their faces had been burned and swollen. Perhaps only about ten people could be identified.” These are the words Ms. Kato heard from the late Fumiko Sakamoto and other people—bereaved families who had searched for their daughters.

Ms. Kato said, “As a matter of fact, there was a suggestion, at first, that the third- and fourth-year students, as well as those in the advanced course should be mobilized to demolish homes to create fire lanes on August 6. But the late Yoshiyuki Kutsuki, a teacher who was in charge of older students, had prevented it, saying that the students were tired and needed to rest. If I had taken part in demolition of homes, I would have died, too.”

The advanced course was abolished at the end of the war, and Ms. Kato married when she was 20. While busy raising her four children, she helped a memorial service for A-bomb victims held August 6 every year. On the occasion of the 40th anniversary of the atomic bombing, she closely examined the school register with Ms. Sakamoto and others, and the alumni union produced a memorial bearing the names of the victims and erected it near the A-bomb monument to her school.

Ms. Kato began sharing her A-bomb account in peace education classes at Funairi High School last year, when she turned 90. She said, “Everybody served our country frantically and died. Once a war begins, our human rights are deprived and everything is destroyed.” She is planning to share her account with her “juniors” at Funairi High School, who are of her great-grandchildren’s generation, this summer, too.

Nothing can take the place of school life

Ms. Kato, who experienced the atomic bombing when she was 16 years old, was around the same age as me. She was brought up as one of “the children of the Empire” and she thought that it was an honor to sacrifice her life for the good of the nation. She talked about the importance of education. I learned from her that nothing can take the place of my school life. I have a dream to work in the environment for education in the future. I want to respect the autonomy of the child who will lead the future and to hand down a peaceful community. (Yukiho Saito, 18)

A war robs us of precious people

Ms. Kato said, “I thought it was the end of the world when I saw Ninoshima Island from Hiroshima Station.” When I looked up the island on a map, I was surprised to find it was really far from the station.” Ms. Kato looked sad when she talked about friends who had died, and I thought war is unforgivable as it robs us of precious people. I want to listen to as many people as possible and to honestly write what I felt in order to end war. (Chihiro Yamase, 13)

Conveying A-bomb survivors’ message to the next generation

When Ms. Kato was asked to talk about her experience, she thought that she had to talk because she had survived the atomic bombing. I strongly felt her passion for conveying what happened on that day to us. I want to talk about A-bomb survivors’ accounts to my family members and friends to hand down Ms. Kato’s desire, now that I know, to the next generation and to continue making small efforts to think about war and peace. (Shino Taguchi, 14)

(Originally published on June 22, 2020)

To convey chagrin of Hiroshima First Municipal Girls’ School students to young people

Yachiyo Kato (née Tominaga), now 91, who graduated from Hiroshima First Municipal Girls’ School (now Funairi High School), believes she was able to survive the atomic bombing thanks to a teacher’s decision. With the thought that she was allowed to survive A-bombing to convey her experience to young people, she has devoted half of her life to passing on the A-bomb accounts of students from Hiroshima First Municipal Girls’ School.

Ms. Kato entered the school in April 1941 and went on to the advanced course, which was established during the war in the spring of 1945. She was making machine-gun bullets as a mobilized student every day at the factory of the Japan Steel Works located in Nishikaniya-cho (now part of Minami Ward). August 6 fell on a day when the factory was closed once each month because of a shortage of electric power.

Ms. Kato had plans to go to the island of Miyajima with friends. She left her home, located in Mukainada-nakamachi (now part of Minami Ward), early in the morning, and when she was waiting for her friends in front of Koi Station (now Hiroden-Nishihiroshima Station) a little past eight, she was suddenly blown about 10 meters by the A-bomb blast and lost consciousness.

She was about 2.5 kilometers from the hypocenter, but she does not remember the bomb’s flash of light or its roar. When she came to, she found lunch boxes and wooden clogs scattered about, and students in a lower grade who were with her, had been injured from glass fragments piercing her cheeks and shoulders. She received first aid at Kusatsu National School (now Kusatsu Elementary School), which functioned as a temporary relief station, and headed to her home, avoiding fires.

On her way home, she was exposed to the black and thick rain and saw people whose skin hung down in strips, students nearly naked, and women with hair standing upright wherever she went. When she arrived at her home, it was past 8:00 p.m.

Two days later, a woman involved with a women’s group who took part in the rescue efforts at Aosaki National School (now Aosaki Elementary School) in the neighborhood, came to inform Ms. Kato that her classmate, Tsuneko Yoshimoto was staying there. Ms. Yoshimoto was one of Ms. Kato’s friends with whom she had planned to go to Miyajima. Ms. Yoshimoto was exposed to the atomic bomb on a streetcar when it was passing near the Dobashi streetcar stop, and then was carried there.

Ms. Kato decided to bring her to Ms. Kato’s home to take care of her until Ms. Yoshimoto’s mother came to get her. She laid her on the futon and tried to give her grated cucumber and crushed tomato, but she immediately threw it up. In retrospect, the inside of her mouth was bright yellow perhaps because of the effects of her radiation exposure. Several days later, Ms. Yoshimoto was brought back home in Midori-machi (now part of Minami Ward) on a two-wheel cart and passed away around August 24.

Hiroshima First Municipal Girls’ School lost a total of 676 people including ten teachers in the A-bomb attack. Five hundred forty one first- and second-year students were mobilized to demolish homes to create fire lanes south of what is now Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park in the city’s Naka Ward, were exposed to the A-bomb’s heat and blast around 500 meters from the hypocenter. All of them died. “Most students’ eyeballs had popped from their sockets and their faces had been burned and swollen. Perhaps only about ten people could be identified.” These are the words Ms. Kato heard from the late Fumiko Sakamoto and other people—bereaved families who had searched for their daughters.

Ms. Kato said, “As a matter of fact, there was a suggestion, at first, that the third- and fourth-year students, as well as those in the advanced course should be mobilized to demolish homes to create fire lanes on August 6. But the late Yoshiyuki Kutsuki, a teacher who was in charge of older students, had prevented it, saying that the students were tired and needed to rest. If I had taken part in demolition of homes, I would have died, too.”

The advanced course was abolished at the end of the war, and Ms. Kato married when she was 20. While busy raising her four children, she helped a memorial service for A-bomb victims held August 6 every year. On the occasion of the 40th anniversary of the atomic bombing, she closely examined the school register with Ms. Sakamoto and others, and the alumni union produced a memorial bearing the names of the victims and erected it near the A-bomb monument to her school.

Ms. Kato began sharing her A-bomb account in peace education classes at Funairi High School last year, when she turned 90. She said, “Everybody served our country frantically and died. Once a war begins, our human rights are deprived and everything is destroyed.” She is planning to share her account with her “juniors” at Funairi High School, who are of her great-grandchildren’s generation, this summer, too.

Teenagers’ impressions

Nothing can take the place of school life

Ms. Kato, who experienced the atomic bombing when she was 16 years old, was around the same age as me. She was brought up as one of “the children of the Empire” and she thought that it was an honor to sacrifice her life for the good of the nation. She talked about the importance of education. I learned from her that nothing can take the place of my school life. I have a dream to work in the environment for education in the future. I want to respect the autonomy of the child who will lead the future and to hand down a peaceful community. (Yukiho Saito, 18)

A war robs us of precious people

Ms. Kato said, “I thought it was the end of the world when I saw Ninoshima Island from Hiroshima Station.” When I looked up the island on a map, I was surprised to find it was really far from the station.” Ms. Kato looked sad when she talked about friends who had died, and I thought war is unforgivable as it robs us of precious people. I want to listen to as many people as possible and to honestly write what I felt in order to end war. (Chihiro Yamase, 13)

Conveying A-bomb survivors’ message to the next generation

When Ms. Kato was asked to talk about her experience, she thought that she had to talk because she had survived the atomic bombing. I strongly felt her passion for conveying what happened on that day to us. I want to talk about A-bomb survivors’ accounts to my family members and friends to hand down Ms. Kato’s desire, now that I know, to the next generation and to continue making small efforts to think about war and peace. (Shino Taguchi, 14)

(Originally published on June 22, 2020)