Chugoku Shimbun and Nishinippon Shimbun partner on project detailing history of Peace Declarations delivered in A-bombed cities

Jun. 29, 2020

by Kyoko Niiyama from Chugoku Shimbun and Eiko Tokumasu from Nagasaki Branch of Nishinippon Shimbun, Staff Writers

Each year, a Peace Declaration is delivered by the mayor at each city’s Peace Memorial Ceremony, on August 6 in Hiroshima, and on August 9 in Nagasaki. Although the declarations’ histories and ways by which their citizens became involved in the draft-making process differ, the two declarations are equally significant in that they represent the voices of the A-bombed cities sent to the world. This year marks the 75th anniversary of the atomic bombings. Amid the global COVID-19 pandemic, the effectiveness by which the A-bombed cities’ messages can be delivered might be called into question. Herein, we look at the histories and the present situation surrounding the peace declarations of the two A-bombed cities.

The Nagasaki City government sees the Peace Declaration, read out by the mayor who represents its citizens, as representing the voices of the people of Nagasaki. The declaration includes messages and words carefully considered by a draft committee, which consists of A-bomb survivors and people with various titles from all walks of life. According to the city’s Peace Promotion Division, the declaration tries to incorporate words that everyone can readily understand with the same interpretation. With this idea, the Nagasaki Peace Declaration often uses forthright language.

“It wouldn’t be persuasive enough without graphic description or the real voices of survivors,” one committee participant said. “We should stress that the risk of nuclear weapons use is increasing,” indicated another. Attendees made numerous comments regarding this year’s rough draft submitted by Mayor Tomihisa Taue at the first meeting held in early June. The draft committee consists of 15 members, including A-bomb survivors, second-generation A-bomb survivors, experts on nuclear issues, and university graduate students. All meetings, which only the media could observe until five years ago, are now open to the public.

The late Hitoshi Motojima, Nagasaki mayor from 1979 to 1995, was the first to express “Nagasaki’s ideas” in the declarations. During his first year in office, he touched on the responsibility of the United States for the atomic bombings, posing the question, “Why do we leave unquestioned U.S. responsibility for the atomic bombings that indiscriminately killed and wounded so many people.”

The first Nagasaki Peace Declaration was delivered three years after the end of World War II, when Japan was still occupied by Allied Forces. For that reason, the declaration included such language as “the atomic bombing of Nagasaki put to an end to the war.” Slowly, the content changed with the times, and started to incorporate criticisms of nuclear testing and the Vietnam War, which involved many civilians. Mr. Motojima’s unfiltered criticism of the United States, however, was unusual.

The members of the original draft committee, composed mainly of city employees, were replaced with physicians and scientific researchers involved in the medical treatment of A-bomb survivors. In 1981, when the three non-nuclear principles were under pressure, he appealed to then Prime Minister Zenko Suzuki by name: “Please let the Japanese people know the truth.” In 1988, he remarked at a city council meeting, “I believe the Emperor has responsibility for the war.” In the following year’s Peace Declaration, he mentioned that the Pacific War started with the Pearl Harbor attack and ended with the atomic bombing of Nagasaki, expressing deep regret for Japan’s wartime aggressions. Despite the fact that he was shot in 1990, Mayor Motojima continued to insert the concept of “regret” in his peace declarations.

Noboru Tazaki, 76, a former city employee who was involved in those days, said that he felt that Nagasaki gradually started to receive recognition at international conferences and other venues at around that time.

This “liberal” spirit was taken up by the next mayor, the late Iccho Ito. In 2005, he criticized the United States’ negative stance toward the abolition of nuclear weapons. “They ignore international consensus and don’t even attempt to change their stance of clinging to nuclear deterrence.” The current mayor, Mr. Taue, also reproaches the Japanese national government for not getting out from underneath the nuclear umbrella, an attitude that “the A-bombed cities will never understand.”

Masao Tomonaga, 77, honorary director of the Japanese Red Cross Nagasaki Genbaku Hospital and a committee member since 2001, said, “Together with the mayor, we polish the speech after hearing the opinions of each of the members. I feel that the ideas and opinions of the citizens certainly tend to be directly reflected in the language of the Peace Declaration.”

“We, Hiroshima’s citizens, renew our commitment to establishment of peace, expressing our burning desire for peace.” The Hiroshima’s first Peace Declaration was delivered by then Mayor Shinso Hamai at the first Peace Festival (now the Peace Memorial Ceremony) in 1947, two years after the atomic bombing. The declaration served as an appeal aimed at consoling the souls of the victims and renouncing war.

Some years there was no Peace Declaration. With the outbreak of the Korean War, the Hiroshima Peace Festival was suspended in 1950 following orders from the General Headquarters for the Allied Forces (GHQ). Although the Peace Memorial Ceremony was held the next year, the mayor simply delivered a welcome address. Thereafter, the Peace Declaration has been delivered by the Hiroshima mayor every year since 1952, the year in which the occupation of Japan formally ended.

The current mayor Kazumi Matsui holds a total of three closed-door meetings from May to July every year to gather the opinions of A-bomb survivors, university professors, and representatives of peace groups. He develops a draft of the Peace Declaration with city staff based on those opinions. This year, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the first meeting consisted of participant opinions being collected in writing.

According to the city’s Peace Promotion Division, ideas including a “warning about the ‘my country first policy’ amid the spread of the novel coronavirus” were submitted by seven committee members. A second such meeting has already been held in writing. Committee members are scheduled to gather in mid-July for the third meeting.

After assuming office in 2011, Mr. Matsui called for submission of experiences of the atomic bombing and formed a selection committee consisting of community leaders. The committee selected the A-bomb accounts submitted by two survivors to be incorporated into the Peace Declaration. During his second term, he halted this collection of such accounts and replaced the selection committee with informal meetings. Mr. Matsui’s Peace Declaration has more direct citizen involvement compared with the declarations of past mayors. Last year, he cited a Japanese tanka poem composed by a survivor, and two years ago he incorporated into the declaration the stories of two survivors.

The Peace Declaration, composed with consideration paid to international circumstances and the global status of nuclear weapons at the time, is regarded as a message delivered in the name of the mayor, a representative of Hiroshima’s citizens.

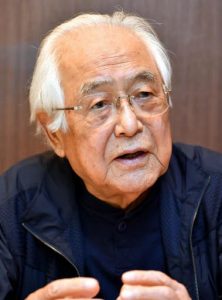

Takashi Hiraoka, 92, served two terms over the span of eight years as Hiroshima mayor. After assuming the post in 1991, he referred to Japan’s “colonial domination and war” on Asia and in the Pacific and offered an apology for such actions. He said in an interview, “While the Mayor invites a broad range of opinions from the public, in the end the mayor takes responsibility drafting the document.”

Tadatoshi Akiba, who served three terms as the city’s mayor for 12 years starting in 1999, called for the “realization of the abolition of nuclear weapons by 2020.” The individuality of each mayor and historical background are reflected in the Peace Declaration document. In recent years, arguments surrounding the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW) have found their way into the declaration.

The Peace Declarations in 2017 and 2018 did not include language urging the Japanese government to sign and ratify the treaty. Last July, six A-bomb survivors’ groups in the prefecture, including the two Hiroshima Prefectural Confederation of A-bomb Sufferers Organizations (Hiroshima Hidankyo), submitted a request to the Hiroshima City government. Pushed in this way, Mayor Matsui demanded that the national government sign and ratify the treaty as the “wish of A-bomb survivors.” Toshiyuki Mimaki, 78, acting chair of the Hiroshima Hidankyo (chaired by Sunao Tsuboi) said, “I want the mayor to implore the Japanese government based on his own will and in his own words. That would serve as encouragement for the survivors.”

The Chugoku Shimbun interviewed Takashi Hiraoka, former mayor of Hiroshima, asking him about the role and the significance of the Peace Declaration.

Will pay attention to what mayors of A-bombed cities say amid the COVID 19 pandemic

The Peace Declaration contains our sincere prayers for the repose of the souls of victims of the atomic bombings and an appeal for the abolition of nuclear weapons based on the Hiroshima’s philosophy of peace.

The mayor’s own perceptions of history and outlook on the world are also reflected in the message. In my first Peace Declaration, I referred to Japanese military aggression during the war because I thought it was important to accept Japan’s historical responsibility in order to convey Hiroshima’s wish for peace before hosting the 1994 Asian Games. Of course, there was opposition to my idea.

In 1998, I called for establishment of a treaty to ban the use of nuclear weapons. We can protest the government, and have the responsibility to do so, precisely because we are the A-bombed cities. The mayor should criticize the government’s stance on the TPNW and explicitly request that the national government sign and ratify the treaty. In that regard, I am not completely satisfied with the recent Peace Declarations.

The Peace Declarations of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, which are often compared, have their own significance. The two cities experienced different historical backgrounds and reconstruction processes after the war. We should especially not forget that Hiroshima was a “military city.” The messages delivered on August 6 and August 9 are interpreted by the world as the “collective voice of the A-bombed cities.” The Peace Declaration has that much influence.

I keenly realize the crisis for humanity posed by the COVID-19 pandemic. Nuclear weapons, too, are a threat to humanity. I will pay my attention to what messages are delivered from the A-bombed cities at this year’s anniversary of the atomic bombings amid the coronavirus pandemic.

With the A-bomb survivors continuing to age, there is an urgent need to pass down the legacy of their experiences of the atomic bombings. In that sense, the Peace Declaration could have a new, additional role as a message to future generations of our hopes for peace and appeal for the abolition of nuclear weapons. I would like young people to read past mayors’ Peace Declarations and understand what message has historically been delivered from the A-bombed cities.

History of Hiroshima Peace Declaration (Mayor)

1947 First Peace Declaration was delivered at First Peace Festival. (Shinso Hamai)

1950 Ceremony was canceled following orders from GHQ. No Peace Declaration was issued. (Shinso Hamai)

1951 “Welcome Address” was delivered at Peace Memorial Ceremony instead of Peace Declaration. (Shinso Hamai)

1956 Referred to campaigns against atomic and hydrogen bombs. (Tadao Watanabe)

1963 Expressed gratification that a pact for partial ban of nuclear weapons had been concluded among US, UK, and USSR. (Shinso Hamai)

1973 Condemned nuclear tests as “criminal act against all mankind.” (Setsuo Yamada)

1979 Mentioned that “Japanese government has begun consultations to work out a basic structure of thinking on the measures to aid the A-bomb survivors and to re-examine its present measures. We place much of our hope for the future on this effort.” (Takeshi Araki)

1990 Referred to effort to “promote support for those hibakusha resident

on Korean Peninsula, US, and elsewhere.” (Takeshi Araki)

1991 Offered apology to peoples of Asia and Pacific. (Takashi Hiraoka)

1997 Called on Japanese government to “devise security arrangements that do not rely upon a nuclear umbrella.” (Takashi Hiraoka)

1999 Pointed out that nuclear weapons are “absolute evil and cause humankind’s extinction.” (Tadatoshi Akiba)

2003 Referred to “nuclear weapons ban treaty” and “black rain.” (Tadatoshi Akiba)

2009 Expressed support for then US President Obama and introduced expression “Obamajority,” with declaration’s conclusion in English. (Tadatoshi Akiba)

2011 Essays solicited by city from A-bomb survivors were quoted in statement for first time. (Kazumi Matsui)

2019 Called on Japanese government to sign and ratify Treaty on Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, indicating it was A-bomb survivor’s desire. (Kazumi Matsui)

(Originally published on June 29, 2020)

Each year, a Peace Declaration is delivered by the mayor at each city’s Peace Memorial Ceremony, on August 6 in Hiroshima, and on August 9 in Nagasaki. Although the declarations’ histories and ways by which their citizens became involved in the draft-making process differ, the two declarations are equally significant in that they represent the voices of the A-bombed cities sent to the world. This year marks the 75th anniversary of the atomic bombings. Amid the global COVID-19 pandemic, the effectiveness by which the A-bombed cities’ messages can be delivered might be called into question. Herein, we look at the histories and the present situation surrounding the peace declarations of the two A-bombed cities.

Nagasaki: City reflects citizens’ opinions in the statement, disclosing draft committee’s discussions on issue

The Nagasaki City government sees the Peace Declaration, read out by the mayor who represents its citizens, as representing the voices of the people of Nagasaki. The declaration includes messages and words carefully considered by a draft committee, which consists of A-bomb survivors and people with various titles from all walks of life. According to the city’s Peace Promotion Division, the declaration tries to incorporate words that everyone can readily understand with the same interpretation. With this idea, the Nagasaki Peace Declaration often uses forthright language.

“It wouldn’t be persuasive enough without graphic description or the real voices of survivors,” one committee participant said. “We should stress that the risk of nuclear weapons use is increasing,” indicated another. Attendees made numerous comments regarding this year’s rough draft submitted by Mayor Tomihisa Taue at the first meeting held in early June. The draft committee consists of 15 members, including A-bomb survivors, second-generation A-bomb survivors, experts on nuclear issues, and university graduate students. All meetings, which only the media could observe until five years ago, are now open to the public.

The late Hitoshi Motojima, Nagasaki mayor from 1979 to 1995, was the first to express “Nagasaki’s ideas” in the declarations. During his first year in office, he touched on the responsibility of the United States for the atomic bombings, posing the question, “Why do we leave unquestioned U.S. responsibility for the atomic bombings that indiscriminately killed and wounded so many people.”

The first Nagasaki Peace Declaration was delivered three years after the end of World War II, when Japan was still occupied by Allied Forces. For that reason, the declaration included such language as “the atomic bombing of Nagasaki put to an end to the war.” Slowly, the content changed with the times, and started to incorporate criticisms of nuclear testing and the Vietnam War, which involved many civilians. Mr. Motojima’s unfiltered criticism of the United States, however, was unusual.

The members of the original draft committee, composed mainly of city employees, were replaced with physicians and scientific researchers involved in the medical treatment of A-bomb survivors. In 1981, when the three non-nuclear principles were under pressure, he appealed to then Prime Minister Zenko Suzuki by name: “Please let the Japanese people know the truth.” In 1988, he remarked at a city council meeting, “I believe the Emperor has responsibility for the war.” In the following year’s Peace Declaration, he mentioned that the Pacific War started with the Pearl Harbor attack and ended with the atomic bombing of Nagasaki, expressing deep regret for Japan’s wartime aggressions. Despite the fact that he was shot in 1990, Mayor Motojima continued to insert the concept of “regret” in his peace declarations.

Noboru Tazaki, 76, a former city employee who was involved in those days, said that he felt that Nagasaki gradually started to receive recognition at international conferences and other venues at around that time.

This “liberal” spirit was taken up by the next mayor, the late Iccho Ito. In 2005, he criticized the United States’ negative stance toward the abolition of nuclear weapons. “They ignore international consensus and don’t even attempt to change their stance of clinging to nuclear deterrence.” The current mayor, Mr. Taue, also reproaches the Japanese national government for not getting out from underneath the nuclear umbrella, an attitude that “the A-bombed cities will never understand.”

Masao Tomonaga, 77, honorary director of the Japanese Red Cross Nagasaki Genbaku Hospital and a committee member since 2001, said, “Together with the mayor, we polish the speech after hearing the opinions of each of the members. I feel that the ideas and opinions of the citizens certainly tend to be directly reflected in the language of the Peace Declaration.”

Hiroshima: Mayor sends out his wish to the world with quotations from A-bomb survivors

“We, Hiroshima’s citizens, renew our commitment to establishment of peace, expressing our burning desire for peace.” The Hiroshima’s first Peace Declaration was delivered by then Mayor Shinso Hamai at the first Peace Festival (now the Peace Memorial Ceremony) in 1947, two years after the atomic bombing. The declaration served as an appeal aimed at consoling the souls of the victims and renouncing war.

Some years there was no Peace Declaration. With the outbreak of the Korean War, the Hiroshima Peace Festival was suspended in 1950 following orders from the General Headquarters for the Allied Forces (GHQ). Although the Peace Memorial Ceremony was held the next year, the mayor simply delivered a welcome address. Thereafter, the Peace Declaration has been delivered by the Hiroshima mayor every year since 1952, the year in which the occupation of Japan formally ended.

The current mayor Kazumi Matsui holds a total of three closed-door meetings from May to July every year to gather the opinions of A-bomb survivors, university professors, and representatives of peace groups. He develops a draft of the Peace Declaration with city staff based on those opinions. This year, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the first meeting consisted of participant opinions being collected in writing.

According to the city’s Peace Promotion Division, ideas including a “warning about the ‘my country first policy’ amid the spread of the novel coronavirus” were submitted by seven committee members. A second such meeting has already been held in writing. Committee members are scheduled to gather in mid-July for the third meeting.

After assuming office in 2011, Mr. Matsui called for submission of experiences of the atomic bombing and formed a selection committee consisting of community leaders. The committee selected the A-bomb accounts submitted by two survivors to be incorporated into the Peace Declaration. During his second term, he halted this collection of such accounts and replaced the selection committee with informal meetings. Mr. Matsui’s Peace Declaration has more direct citizen involvement compared with the declarations of past mayors. Last year, he cited a Japanese tanka poem composed by a survivor, and two years ago he incorporated into the declaration the stories of two survivors.

The Peace Declaration, composed with consideration paid to international circumstances and the global status of nuclear weapons at the time, is regarded as a message delivered in the name of the mayor, a representative of Hiroshima’s citizens.

Takashi Hiraoka, 92, served two terms over the span of eight years as Hiroshima mayor. After assuming the post in 1991, he referred to Japan’s “colonial domination and war” on Asia and in the Pacific and offered an apology for such actions. He said in an interview, “While the Mayor invites a broad range of opinions from the public, in the end the mayor takes responsibility drafting the document.”

Tadatoshi Akiba, who served three terms as the city’s mayor for 12 years starting in 1999, called for the “realization of the abolition of nuclear weapons by 2020.” The individuality of each mayor and historical background are reflected in the Peace Declaration document. In recent years, arguments surrounding the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW) have found their way into the declaration.

The Peace Declarations in 2017 and 2018 did not include language urging the Japanese government to sign and ratify the treaty. Last July, six A-bomb survivors’ groups in the prefecture, including the two Hiroshima Prefectural Confederation of A-bomb Sufferers Organizations (Hiroshima Hidankyo), submitted a request to the Hiroshima City government. Pushed in this way, Mayor Matsui demanded that the national government sign and ratify the treaty as the “wish of A-bomb survivors.” Toshiyuki Mimaki, 78, acting chair of the Hiroshima Hidankyo (chaired by Sunao Tsuboi) said, “I want the mayor to implore the Japanese government based on his own will and in his own words. That would serve as encouragement for the survivors.”

Interview with Takashi Hiraoka, former mayor of Hiroshima

The Chugoku Shimbun interviewed Takashi Hiraoka, former mayor of Hiroshima, asking him about the role and the significance of the Peace Declaration.

Will pay attention to what mayors of A-bombed cities say amid the COVID 19 pandemic

The Peace Declaration contains our sincere prayers for the repose of the souls of victims of the atomic bombings and an appeal for the abolition of nuclear weapons based on the Hiroshima’s philosophy of peace.

The mayor’s own perceptions of history and outlook on the world are also reflected in the message. In my first Peace Declaration, I referred to Japanese military aggression during the war because I thought it was important to accept Japan’s historical responsibility in order to convey Hiroshima’s wish for peace before hosting the 1994 Asian Games. Of course, there was opposition to my idea.

In 1998, I called for establishment of a treaty to ban the use of nuclear weapons. We can protest the government, and have the responsibility to do so, precisely because we are the A-bombed cities. The mayor should criticize the government’s stance on the TPNW and explicitly request that the national government sign and ratify the treaty. In that regard, I am not completely satisfied with the recent Peace Declarations.

The Peace Declarations of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, which are often compared, have their own significance. The two cities experienced different historical backgrounds and reconstruction processes after the war. We should especially not forget that Hiroshima was a “military city.” The messages delivered on August 6 and August 9 are interpreted by the world as the “collective voice of the A-bombed cities.” The Peace Declaration has that much influence.

I keenly realize the crisis for humanity posed by the COVID-19 pandemic. Nuclear weapons, too, are a threat to humanity. I will pay my attention to what messages are delivered from the A-bombed cities at this year’s anniversary of the atomic bombings amid the coronavirus pandemic.

With the A-bomb survivors continuing to age, there is an urgent need to pass down the legacy of their experiences of the atomic bombings. In that sense, the Peace Declaration could have a new, additional role as a message to future generations of our hopes for peace and appeal for the abolition of nuclear weapons. I would like young people to read past mayors’ Peace Declarations and understand what message has historically been delivered from the A-bombed cities.

History of Hiroshima Peace Declaration (Mayor)

1947 First Peace Declaration was delivered at First Peace Festival. (Shinso Hamai)

1950 Ceremony was canceled following orders from GHQ. No Peace Declaration was issued. (Shinso Hamai)

1951 “Welcome Address” was delivered at Peace Memorial Ceremony instead of Peace Declaration. (Shinso Hamai)

1956 Referred to campaigns against atomic and hydrogen bombs. (Tadao Watanabe)

1963 Expressed gratification that a pact for partial ban of nuclear weapons had been concluded among US, UK, and USSR. (Shinso Hamai)

1973 Condemned nuclear tests as “criminal act against all mankind.” (Setsuo Yamada)

1979 Mentioned that “Japanese government has begun consultations to work out a basic structure of thinking on the measures to aid the A-bomb survivors and to re-examine its present measures. We place much of our hope for the future on this effort.” (Takeshi Araki)

1990 Referred to effort to “promote support for those hibakusha resident

on Korean Peninsula, US, and elsewhere.” (Takeshi Araki)

1991 Offered apology to peoples of Asia and Pacific. (Takashi Hiraoka)

1997 Called on Japanese government to “devise security arrangements that do not rely upon a nuclear umbrella.” (Takashi Hiraoka)

1999 Pointed out that nuclear weapons are “absolute evil and cause humankind’s extinction.” (Tadatoshi Akiba)

2003 Referred to “nuclear weapons ban treaty” and “black rain.” (Tadatoshi Akiba)

2009 Expressed support for then US President Obama and introduced expression “Obamajority,” with declaration’s conclusion in English. (Tadatoshi Akiba)

2011 Essays solicited by city from A-bomb survivors were quoted in statement for first time. (Kazumi Matsui)

2019 Called on Japanese government to sign and ratify Treaty on Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, indicating it was A-bomb survivor’s desire. (Kazumi Matsui)

(Originally published on June 29, 2020)