Hiroshima asks: Toward the 70th anniversary of the atomic bombing

Dec. 7, 2015

by Yumi Kanazaki, Staff Writer

Seventy years have passed since the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki by the United States. Today nine nations possess extremely dangerous nuclear weapons. Of these, the U.S. is the strongest. In the presidential election campaign, Barack Obama pledged to bring an end to the Cold War era notion of nations threatening each other with large numbers of nuclear weapons. But, in fact, the administration has taken a step backward. Taking a close look at the situation in the U.S., Japan, which seeks the protection of the nuclear umbrella, emerges as one factor.

Another factor: consideration for Japan, which seeks the protection of the “nuclear umbrella”

What should be noted is that there is more to the nuclear policy of the Obama administration than just the modernization of the nation’s nuclear weapons. When traveling around the U.S. I heard a surprising number of people say that the U.S. nuclear arsenal existed out of consideration for the concerns of allies that seek the protection of the nuclear umbrella.

In May 2009 the Congressional Commission on the Strategic Posture of the United States, a bipartisan commission, issued its final report to Congress. An important document prepared by commission members, who included former government officials, the report’s comments on tactical nuclear weapons attracted particular attention. Referring to the plan to retire the nuclear Tomahawk land-attack cruise missile (TLAM/N), the report stated: “In our work as a Commission it has become clear to us that some U.S. allies in Asia would be very concerned by TLAM/N retirement.”

“This means Japan,” said Morton H. Halperin, 76, who was heavily involved in the negotiations for the return of Okinawa to Japan and also served as a Special Assistant to the President and in other posts during the administration of President Bill Clinton. As a Senior Advisor for the Open Society Institute, he now works in an office near the White House.

Mr. Halperin said that Japan has been told very little about when and how the U.S. will use its nuclear weapons. So the slightest change in policy raises concern about the weakening of the nuclear umbrella. He said he had the feeling there were communication problems between the U.S. and Japan and said there was alarm on the U.S. side about the prospect of Japan arming itself with its own nuclear weapons out of a sense of insecurity.

The report by the commission advocates “establishing a much more extensive dialogue with Japan on nuclear issues… Such a dialogue with Japan would also increase the credibility of extended deterrence.” In February 2010 the governments of Japan and the U.S. held the first Japan-U.S. Extended Deterrence Dialogue to discuss deterrence, including under the nuclear umbrella. Officials from the State and Defense departments attended on behalf of the U.S., while Japan was represented by officials from the Foreign and Defense ministries. Meetings have been held regularly since then. Mr. Halperin expressed satisfaction saying that his opinions had been included in the report and reflected in policy.

In April of 2010, the Obama administration issued its Nuclear Posture Review (NPR) to Congress in which it outlined its nuclear weapons policy. The review included a reference to the retirement of the TLAM/N and stated that the government’s intention in this regard had been conveyed in advance to Japan and other allies for whom the nuclear umbrella is provided.

During the Obama administration, there has been more sharing of information on nuclear weapons between the U.S. and Japan. Ironically, it seems that there is a move toward unprecedented integration of policy between the U.S. and Japan, not only in terms of conventional military forces but also in terms of U.S. nuclear strategy.

Instead of attack submarines, display threat from the air

The following are edited excerpts from comments by Bradley Roberts, former deputy assistant Secretary of Defense for nuclear and missile defense policy, who was involved in the formulation of the 2010 Nuclear Posture Review (NPR). Mr. Roberts outlined his thoughts on the current status of the nuclear umbrella.

China is further accelerating the modernization of its arsenal, and North Korea is developing nuclear weapons and missiles. The security environment in East Asia is changing. Meanwhile enhancing the deterrence that the U.S. provides to its allies is an emerging issue. People tend to think that the nuclear umbrella is the only way to do that, but that is not the case. Having nuclear weapons means being prepared for extremely limited situations.

The umbrella, which is not limited to nuclear weapons, also represents further integration of the military capabilities of Japan and the U.S.

The unique deterrence function of nuclear weapons will certainly be retained. At the same time, overall extended deterrence through conventional weapons, whose threshold for use is lower, and missile defense will be strengthened. It is U.S. policy to have its allies play roles in non-nuclear areas.

The Obama administration stresses that it has put much more emphasis on discussions with its allies than previous administrations.

During the 16 months we worked on formulating the NPR, we had talks with about 30 countries a total of 70 times. We also gave a detailed explanation of the retirement of the Navy’s nuclear Tomahawk land-attack cruise missile to Japan and our other allies.

If necessary, fighter bombers that can carry nuclear bombs, such as the F-15, and long-range bombers, such as the B-2, can be deployed forward in Guam or anywhere in the world. While they are more visible than submarines, they can display a threat to enemies and visually demonstrate the resolve of the U.S. to its allies. So we explained that we would have nuclear/non-nuclear dual-capable aircraft and modernize our capabilities. Japan expressed support for this policy.

I was in charge of the Extended Deterrence Dialogue, during which deterrence, including the nuclear umbrella, is discussed.

It is my understanding that the U.S. said virtually nothing to Japan about nuclear weapons. We felt we should enhance the transparency of our nuclear policy to the Japanese government. What we had in mind was the North American Treaty Organization (NATO), [with which the U.S. shares its nuclear policy]. We must give Japan an opportunity to get first-hand information on U.S. military capability, including nuclear deterrence. We now have a discussion process like that of NATO.

We have invited Japanese government officials to bases where nuclear weapons are deployed. We also explain situations based on what Japan is interested in. For example, the deployment of the Prompt Global Strike plan [for launching attacks with conventional weapons anywhere in the world within one hour].

How should deterrence be enhanced amid the changing security environment? What might North Korea do in the event of a crisis? In what situations will nuclear deterrence be directly involved? Having a shared awareness of these issues and considering them together will forge closer relationships between the U.S. and its allies.

Profile

Born in the U.S. After serving as a member of the research staff at the Institute for Defense Analyses and other institutions was Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Nuclear and Missile Defense Policy from April 2009 through March 2013. Has been a consulting professor at Stanford University till December 2014.

The following are edited excerpts from an interview with Hans Kristensen, a nuclear strategy expert, who stresses that Japan’s voice is critical in the effort to halt the nuclear arms race in the 21st Century.

How do you assess the six years of the Obama administration?

Obama will be remembered more for modernizing nuclear weapons than for reducing nuclear weapons. He has been a disappointment.

In terms of nuclear disarmament, it was all he could do to work out the nuclear arms reduction treaty [New START] with Russia. Now, although the U.S. would never think of conducting an underground nuclear test, there is no prospect of the Senate ratifying the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty.

Clearly the president has had to compromise. In particular, as a Democratic president, he has been pressured to embody the concept of a strong America. And he has a bitter adversarial relationship with Congress.

What about his pledge to reduce the role of nuclear weapons?

As long as you define nuclear weapons as weapons to be used not only in response to an enemy nuclear attack but as weapons that are also useful for deterring attacks by conventional weapons, the numbers can’t be greatly reduced. The key is limiting their role. But the “Report on Nuclear Employment Strategy” that the Defense Department issued in June 2013 basically retained the conventional nuclear plan from the days of the Cold War between the U.S. and the Soviet Union.

If program is to be halted, it must be done now

Is there no change in the trend to increase the budget for nuclear weapons either?

If you look at the budget request for the 2016 fiscal year, which was submitted in early February, it is even clearer. But in the U.S. it’s the legislature – not the executive branch – that has the authority to prepare the budget, so things won’t go that way. The federal government’s expenditures for fiscal reconstruction have recently been subject to mandatory reductions. In that sense, the legislature’s moves will be called into question.

Are there items Hiroshima should be paying attention to?

There are a lot of things, but, to give one example, the plan for the Air Force’s long-range standoff [LRSO] weapons to be deployed on the next-generation long-range bombers. Congress has cut the budget for this project for three years in a row, but the Obama administration has proposed a budget of $36 million, ten times that of the previous fiscal year. That’s not a significant amount, but the intent of the Obama administration can be seen.

The LRSO is only in the study phase, not the engineering phase. Improvements to the existing W80-1 nuclear warhead have yet to be made either. If an effort to halt development is to be made, now is the time. By the 2020s it will be too late.

I’ve heard that along with nuclear warheads the cost will be $30 billion.

Seen from the standpoint of the make-up of U.S. nuclear capability, it can only be regarded as completely redundant. While pointing at northeast Asia on a world map, an Air Force official told me that it was for extended deterrence. That means Japan and South Korea. The U.S. has interested parties who, while broaching the idea of Japan arming itself with nuclear weapons, use that as leverage to increase their budget.

Danger of secret meetings

There’s a gap between the thinking of the people of Hiroshima and the Japanese government. I wonder which is being heard by the U.S. administration.

In that sense, I’m concerned about the Japan-U.S. Extended Deterrence Dialogue. To what extent are they sharing information on the U.S. nuclear strategy? What intent is Japan conveying? Very little information has gotten out.

Insofar as possible, the decision-making process for policy should be transparent and should be verified. The lesson of the so-called “secret nuclear pact” between Japan and the U.S. is the danger of secret meetings between a handful of people from both governments. We must learn from history.

It isn’t easy, but it’s important to focus on the issues at hand and try to nip problems in the bud. It will be difficult to achieve this by just focusing on the goal of eliminating nuclear weapons. I’d like people to realize that a declaration of intent by Japan has even more impact on the U.S. than is thought to be the case in Hiroshima.

Profile

Born in Denmark in 1961. Previously worked for non-governmental organizations, including the international environmental organization Greenpeace. Now serves as director of the Nuclear Information Project at the Federation of American Scientists. Leading researcher on nuclear capability. Calls for the disclosure of information, and data he has compiled that draws on his own research has been published in the yearbook of the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute and other publications and is often cited. This includes data on the number of nuclear weapons countries possess and the make-up of their nuclear capability.

President Obama and U.S. Nuclear Policy

Jan. 2007

Four former top administration officials submit a letter titled “A World Free of Nuclear Weapons” to The Wall Street Journal

Oct. 2007

Prior to the presidential primary election, Democratic candidate Barack Obama gives a foreign policy speech at DePaul University in Chicago in which he says, “America seeks a world in which there are no nuclear weapons.”

Nov. 2008

Elected president

Jan. 2009

Inaugurated

April 2009

Delivers speech in Prague declaring “America's commitment to seek the peace and security of a world without nuclear weapons”

Sept. 2009

Serves as chairman of the U.N. Security Council summit on nuclear disarmament and non-proliferation, resolution “to create the conditions for a world without nuclear weapons” unanimously adopted

Dec. 2009

Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START I) between U.S. and Russia expires with no new agreement in place

Obama awarded Nobel Peace Prize

April 2010

Nuclear Posture Review outlining administration’s stance on nuclear policy formulated; while calling for “reducing the number of nuclear weapons and their role in U.S. national security strategy” it takes no bold steps U.S., Russia sign New START (successor to START I)

Sept. 2010

Administration’s first subcritical nuclear test

Dec. 2010

U.S. Senate ratifies New START

Nov. 2012

Obama re-elected president

June 2013

In a speech in Berlin, Obama says, “Because of the New START Treaty, we’re on track to cut American and Russian deployed nuclear warheads to their lowest levels since the 1950s” and adds that security can be ensured “while reducing our deployed strategic nuclear weapons by up to one-third.”

Defense Department releases its “Report on Nuclear Employment Strategy of the United States”; while stating that the U.S. “seeks the peace and security of a world without nuclear weapons” it also stresses the need to maintain nuclear deterrence

Highlights of Obama’s Prague Speech

•“As a nuclear power, as the only nuclear power to have used a nuclear weapon, the United States has a moral responsibility to act. We cannot succeed in this endeavor alone, but we can lead it, we can start it.”

•“So today, I state clearly and with conviction America's commitment to seek the peace and security of a world without nuclear weapons.”

•“This goal will not be reached quickly –- perhaps not in my lifetime.”

•“To put an end to Cold War thinking, we will reduce the role of nuclear weapons in our national security strategy, and urge others to do the same.”

•“As long as these weapons exist, the United States will maintain a safe, secure and effective arsenal to deter any adversary, and guarantee that defense to our allies.”

•“So today I am announcing a new international effort to secure all vulnerable nuclear material around the world within four years.”

Keywords

Nuclear Umbrella

“Nuclear umbrella” refers to a concept by which the U.S. guarantees the safety of Japan and other allies with nuclear weapons. By being prepared to retaliate with its nuclear capability at any time, the U.S. discourages enemies from attacking its allies. With the Soviet Union and China during the Cold War – and later North Korea – as the presumed enemies, the U.S. has offered the protection of its nuclear umbrella to Japan. The concept of providing security to U.S. allies through the nation’s overall military strength, including conventional weapons, not just nuclear weapons, is referred to as “extended deterrence.”

NATO and nuclear weapons

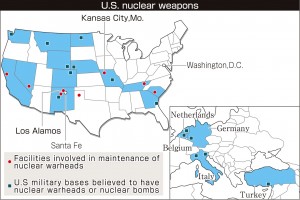

The U.S. also offers the protection of its nuclear umbrella to member nations of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). In addition to strategic nuclear weapons, a total of 200 nuclear bombs out of the 500 tactical nuclear weapons possessed by the U.S. are deployed in Belgium, the Netherlands, Germany, Italy and Turkey. A legacy from the days of preparation against attack by the Soviet Union, this policy is referred to as “nuclear sharing.” Under this policy all of these nations except Turkey are prepared for their military aircraft to use these weapons in an emergency. Nuclear sharing has been criticized as a violation of the Nuclear Non-proliferation Treaty, which stipulates an obligation not to transfer nuclear weapons.

In 1966 NATO established a Nuclear Planning Group. With the exception of France, which attaches importance to the independence of its nuclear capability, 27 member nations attend regular meetings of the group at which they discuss policies for the deployment and use of NATO’s nuclear capability.

■ Kansas City: financial gain from nuclear weapons “unacceptable”

A sign at the gate says “National Security Campus,” calling up images of a leafy college campus. A walking trail traverses the perimeter of the facility’s grounds.

Move from aging facility to new one

Kansas City, Missouri, a Midwestern city known for jazz, has a population of 450,000. On its outskirts lies a facility charged with the maintenance of the nation’s nuclear warheads. The facility handles weapons such as W76 nuclear warheads, which are designed for launch from strategic nuclear submarines, replacing aging internal parts. This extends the useful life of the nuclear warheads by another few decades.

The functions of the aging former facility, which went into operation in the 1940s, were transferred to the new facility in August of last year. The facility is operated by Honeywell International, Inc., a multinational corporation, under a contract with the government. According to a press release, the facility is about three times the size of a baseball stadium and employs about 2,700 people.

Ann Suellentrop, a local peace activist, noted that her area was profiting from weapons of mass destruction and nuclear abolition seemed further and further away. She said nuclear weapons were also unacceptable on ethical grounds.

While the facility was under construction, she and other members of a pacifist organization as well as local lawyers held non-violent protests. A total of 120 protesters were arrested for illegally venturing onto the facility’s premises, but nevertheless they were unable to prevent the implementation of a plan that was approved during the administration of President George W. Bush.

Ms. Suellentrop, a nurse in the newborn nursery at a general hospital, comes in contact with new life every day. A devout Catholic, she believes that nuclear weapons, which kill large numbers of people indiscriminately, are incompatible with the Christian teachings of respect for life and peace.

Around August 6 every year she and other activists gather in a park in downtown Kansas City and float lanterns on a popular pond, recalling Hiroshima and Nagasaki and renewing their vow to continue to tell of the savagery of nuclear weapons.

“What was the Peace Prize all about?”

President Barack Obama delivered his historic speech in Prague, the Czech Republic, in April 2009.

Scott Kovac, 58, is operations and research director for Nuclear Watch New Mexico, which is based in Santa Fe. Santa Fe is about one hour away by car from the Los Alamos National Laboratory, the site of the development of the atomic bomb. Mr. Kovac said the members of his group had hoped the president would take more action and they wondered why he received the Nobel Peace Prize. He said he suspected the people of Hiroshima must have felt the same.

A Waste Isolation Pilot Plant (WIPP) in southern New Mexico carries out the underground disposal of radioactive waste. In February of last year, a drum from Los Alamos that had been brought to the plant burst as the result of a chemical reaction by the contents. Some workers were exposed to radiation as a result, and radioactive materials were released into the atmosphere. The facility has remained closed since then. As a result of this incident, people were once again reminded of the cost to health and environment of maintaining the nation’s nuclear weapons.

Mr. Kovac said with evident frustration that, seen from another perspective, the U.S. had not changed under President Obama and in fact he had been a disappointment.

Current U.S. policy, plans for expanded budget

More than $348 billion in 10 years

After his inauguration as president, Barack Obama made a speech in which he called for “reducing the number of nuclear weapons and their role in U.S. national security strategy.” His predecessor, George W. Bush, had been embarking on the development of a new nuclear warhead and was not cooperative with the international nuclear non-proliferation regime. So President Obama acquired a sharply contrasting image both at home and abroad.

Jon Wolfsthal, 48, served as a special advisor for Nonproliferation and Nuclear Security in the office of the Vice President during President Obama’s first term. He agreed to be interviewed in Washington in December of last year before becoming Senior Director for Arms Control and Nonproliferation at the National Security Council (NSC). Mr. Wolfsthal pointed out, however, that decisions on nuclear policy that have been made under the two administrations are not very different.

He noted that while the Bush administration put priority on acquiring huge amounts of money to finance the Iraq war, it limited the amount of money that went to the nuclear weapons enterprise. But under the Obama administration, expenses have continued to balloon, seemingly in an effort to restore them to their former level.

The life extension program (LEP) for the refurbishment of nuclear warheads that have been in existence since the Cold War, the development of missiles to launch nuclear warheads and the replacement of strategic nuclear submarines that are nearing retirement – these plans to completely modernize the nation’s nuclear weapons systems are all awaiting implementation. The renovation of infrastructure like that in Kansas City is no exception.

According to a report issued by the Congressional Budget Office in January, if the plans formulated by the Defense and Energy departments are implemented, a total of $348 billion is expected to be needed over 10 years from fiscal year 2015. Another report prepared for Congress estimates that the maintenance of the nation’s strategic nuclear weapons will cost $1 trillion over the next 30 years.

If the U.S. were to give up possessing nuclear weapons, there would be no maintenance costs. But in his Prague speech President Obama said, “As long as these weapons exist, the United States will maintain a safe, secure and effective arsenal to deter any adversary, and guarantee that defense to our allies.” It appears as if the administration has focused on carrying this out.

Linton Brooks, 76, served in the Bush administration for five years from 2002 as Under Secretary of Energy for Nuclear Security and Administrator of the National Nuclear Security Administration. He stressed that it is essential to work to maintain the safety and reliability of nuclear weapons from the Cold War era. Mr. Brooks played a leading role in the plan to develop the Reliable Replacement Warhead (RRW), a new nuclear warhead, but this effort was frustrated by Congressional opposition.

While asserting that the pursuit of “a world without nuclear weapons” would put the world in danger by triggering war with conventional weapons, Mr. Brooks also had praise for President Obama. He said that the LEP situation has some elements in common with the RRW and noted that while he had had political failures, some of his ideas have been taken up by the Obama administration.

But President Obama has declared that the U.S. will not develop new nuclear warheads. When asked about that, Mr. Brooks replied with an analogy using classic cars, noting that they remain classic cars even if their tires or some parts are replaced.

The global nuclear arms race is shifting from an emphasis on the quantity of nuclear warheads and delivery devices to exploiting technology to improve quality. Russia and China also aspire to modernize their nuclear weapons, and North Korea is moving forward with the miniaturization of warheads and the development of missiles. But the overwhelming supremacy of the U.S. remains unquestioned. The obligation of nuclear disarmament set forth in the Nuclear Non-proliferation Treaty may become a dead letter.

Resistance to decline in military potential behind setbacks

Disarmament negotiations with Russia stalled

Amid ballooning budgets for nuclear weapons and no decline in their number, how do those who were involved with the Obama administration and experts on nuclear disarmament and non-proliferation view the current situation?

Daryl Kimball, 50, executive director of the Washington-based Arms Control Association, said that a new nuclear arms reduction treaty with Russia had clearly triggered concessions by the president.

The previous treaty, START I, expired in 2009. A new treaty was a high-priority issue for the administration in order to avoid giving Russia free rein in terms of its nuclear arsenal. But ratification of a treaty requires the approval of two thirds of the U.S. Senate. Conservatives in the legislature stressed that the new treaty would weaken the nation’s nuclear capability and sought to make a bigger budget for nuclear weapons part of administration policy. Mr. Kimball said that considering the domestic situation, it was impossible to pin all of one’s hopes on the president.

Politicians, bureaucrats and business people involved in the maintenance of nuclear weapons apparently take a dim view of the notion of a world without nuclear weapons.

James Doyle, 56, is a former nuclear safeguards and security policy specialist at Los Alamos National Laboratory. Two years ago, while working at the laboratory, he submitted an article titled “Why Eliminate Nuclear Weapons?” to a well-known British journal that deals with security issues. In his article he said that “giving up nuclear weapons…may indeed lead to a safer world” and referred to the ideology of nuclear deterrence as a “myth.” Several days after the article was published Mr. Doyle was told by his supervisor that, although officials had reviewed the article before publication, the content was classified. Mr. Doyle was later fired.

But the article can still be read on line. Some people believe that, as the article called for the abolition of nuclear weapons, it incurred the wrath of legislators and the laboratory over-reacted.

Gary Samore, 61, served as White House Coordinator for Arms Control and Weapons of Mass Destruction under President Obama and led the Nuclear Security Summit that was held at the urging of the president. According to Mr. Samore, the administration has troubles both at home and abroad. One key point of the president’s speech in Prague was this declaration: “So today I am announcing a new international effort to secure all vulnerable nuclear material around the world within four years.” The reference to international cooperation elicited a positive response, but Mr. Samore noted that disarmament has its limits. He pointed out that Russian President Vladimir Putin had a negative attitude toward nuclear disarmament and said that with relations between the U.S. and Russia chilly on account of the Ukraine issue, further negotiations on nuclear disarmament were unlikely any time soon.

Two years into his second term, citing a need to leave a legacy to future generations, President Obama directed the restoration of diplomatic relations with Cuba, with which the U.S. has had a long-standing conflict. Many people in Hiroshima would like to see the president once again take up the pledge he made in his speech in Prague and renew in Hiroshima his resolve to bring about a world without nuclear weapons.

Five years ago, Tadatoshi Akiba, then mayor of Hiroshima, met with President Obama at the White House along with a group from the U.S. Conference of Mayors. At that time Jon Wolfsthal, a special advisor for Nonproliferation and Nuclear Security in the office of the Vice President, was also present. Mr. Wolfstahl said that the president was well aware of the invitation to visit Hiroshima but that such a visit could only be made when it was deemed to be clearly in the interest of the nation to do so.

U.S. Nuclear Weapons

Nuclear warheads 7,300

Intercontinental ballistic missiles 450

Strategic nuclear submarines 14

Ballistic missiles on nuclear submarines 288

Long-range bombers with nuclear missions 60

Other Countries’ Nuclear Warheads

Russia 8,000

U.K. 225

France 300

China 250

India 90-110

Pakistan 100-120

Israel 80

North Korea 6-8

(Estimates provided by Hans Kristensen)

Keywords

Strategic and tactical nuclear weapons

Strategic nuclear weapons are long-range nuclear weapons that consist of nuclear warheads mounted on intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBM) and other missiles. The nuclear arms reduction treaty with Russia (New START) sets upper limits on the number of ICBMs at underground sites in the U.S. and ballistic missiles deployed for launch from submarines as well as long-range bombers and the nuclear warheads they carry.

Tactical nuclear weapons, on the other hand, are manufactured for use in war and have a short range. The U.S. has approximately 500 nuclear bombs. Russia is believed to have 2,000, but there have been no negotiations on reductions in tactical nuclear weapons.

Maintenance of U.S. nuclear weapons

The Atomic Energy Commission, a predecessor of the U.S. Department of Energy, produced and developed a large number of nuclear warheads during the Cold War. Today the National Nuclear Security Administration, an agency under the Energy Department, maintains nuclear weapons under its Stockpile Stewardship and Management Program. It also has jurisdiction over national laboratories that have designed and developed nuclear warheads.

The Department of Defense is primarily involved in the development and deployment of weapons that can launch nuclear warheads. ICBMs, strategic nuclear submarines and their ballistic missiles, and long-range bombers are referred to as the three main delivery devices for strategic nuclear weapons. Because the cost of maintaining and updating these weapons is substantial, some people have called for large reductions in their numbers and the elimination of ICBMs, but the Obama administration has decided to maintain them.

(Originally published on February 14, 2015)

What has become of Obama’s pledge?

Seventy years have passed since the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki by the United States. Today nine nations possess extremely dangerous nuclear weapons. Of these, the U.S. is the strongest. In the presidential election campaign, Barack Obama pledged to bring an end to the Cold War era notion of nations threatening each other with large numbers of nuclear weapons. But, in fact, the administration has taken a step backward. Taking a close look at the situation in the U.S., Japan, which seeks the protection of the nuclear umbrella, emerges as one factor.

Japan, U.S. united on deterrence strategy

Another factor: consideration for Japan, which seeks the protection of the “nuclear umbrella”

What should be noted is that there is more to the nuclear policy of the Obama administration than just the modernization of the nation’s nuclear weapons. When traveling around the U.S. I heard a surprising number of people say that the U.S. nuclear arsenal existed out of consideration for the concerns of allies that seek the protection of the nuclear umbrella.

In May 2009 the Congressional Commission on the Strategic Posture of the United States, a bipartisan commission, issued its final report to Congress. An important document prepared by commission members, who included former government officials, the report’s comments on tactical nuclear weapons attracted particular attention. Referring to the plan to retire the nuclear Tomahawk land-attack cruise missile (TLAM/N), the report stated: “In our work as a Commission it has become clear to us that some U.S. allies in Asia would be very concerned by TLAM/N retirement.”

“This means Japan,” said Morton H. Halperin, 76, who was heavily involved in the negotiations for the return of Okinawa to Japan and also served as a Special Assistant to the President and in other posts during the administration of President Bill Clinton. As a Senior Advisor for the Open Society Institute, he now works in an office near the White House.

Mr. Halperin said that Japan has been told very little about when and how the U.S. will use its nuclear weapons. So the slightest change in policy raises concern about the weakening of the nuclear umbrella. He said he had the feeling there were communication problems between the U.S. and Japan and said there was alarm on the U.S. side about the prospect of Japan arming itself with its own nuclear weapons out of a sense of insecurity.

The report by the commission advocates “establishing a much more extensive dialogue with Japan on nuclear issues… Such a dialogue with Japan would also increase the credibility of extended deterrence.” In February 2010 the governments of Japan and the U.S. held the first Japan-U.S. Extended Deterrence Dialogue to discuss deterrence, including under the nuclear umbrella. Officials from the State and Defense departments attended on behalf of the U.S., while Japan was represented by officials from the Foreign and Defense ministries. Meetings have been held regularly since then. Mr. Halperin expressed satisfaction saying that his opinions had been included in the report and reflected in policy.

In April of 2010, the Obama administration issued its Nuclear Posture Review (NPR) to Congress in which it outlined its nuclear weapons policy. The review included a reference to the retirement of the TLAM/N and stated that the government’s intention in this regard had been conveyed in advance to Japan and other allies for whom the nuclear umbrella is provided.

During the Obama administration, there has been more sharing of information on nuclear weapons between the U.S. and Japan. Ironically, it seems that there is a move toward unprecedented integration of policy between the U.S. and Japan, not only in terms of conventional military forces but also in terms of U.S. nuclear strategy.

An interview with Bradley Roberts, former deputy assistant Secretary of Defense for nuclear and missile defense policy

Instead of attack submarines, display threat from the air

The following are edited excerpts from comments by Bradley Roberts, former deputy assistant Secretary of Defense for nuclear and missile defense policy, who was involved in the formulation of the 2010 Nuclear Posture Review (NPR). Mr. Roberts outlined his thoughts on the current status of the nuclear umbrella.

China is further accelerating the modernization of its arsenal, and North Korea is developing nuclear weapons and missiles. The security environment in East Asia is changing. Meanwhile enhancing the deterrence that the U.S. provides to its allies is an emerging issue. People tend to think that the nuclear umbrella is the only way to do that, but that is not the case. Having nuclear weapons means being prepared for extremely limited situations.

The umbrella, which is not limited to nuclear weapons, also represents further integration of the military capabilities of Japan and the U.S.

The unique deterrence function of nuclear weapons will certainly be retained. At the same time, overall extended deterrence through conventional weapons, whose threshold for use is lower, and missile defense will be strengthened. It is U.S. policy to have its allies play roles in non-nuclear areas.

The Obama administration stresses that it has put much more emphasis on discussions with its allies than previous administrations.

During the 16 months we worked on formulating the NPR, we had talks with about 30 countries a total of 70 times. We also gave a detailed explanation of the retirement of the Navy’s nuclear Tomahawk land-attack cruise missile to Japan and our other allies.

If necessary, fighter bombers that can carry nuclear bombs, such as the F-15, and long-range bombers, such as the B-2, can be deployed forward in Guam or anywhere in the world. While they are more visible than submarines, they can display a threat to enemies and visually demonstrate the resolve of the U.S. to its allies. So we explained that we would have nuclear/non-nuclear dual-capable aircraft and modernize our capabilities. Japan expressed support for this policy.

I was in charge of the Extended Deterrence Dialogue, during which deterrence, including the nuclear umbrella, is discussed.

It is my understanding that the U.S. said virtually nothing to Japan about nuclear weapons. We felt we should enhance the transparency of our nuclear policy to the Japanese government. What we had in mind was the North American Treaty Organization (NATO), [with which the U.S. shares its nuclear policy]. We must give Japan an opportunity to get first-hand information on U.S. military capability, including nuclear deterrence. We now have a discussion process like that of NATO.

We have invited Japanese government officials to bases where nuclear weapons are deployed. We also explain situations based on what Japan is interested in. For example, the deployment of the Prompt Global Strike plan [for launching attacks with conventional weapons anywhere in the world within one hour].

How should deterrence be enhanced amid the changing security environment? What might North Korea do in the event of a crisis? In what situations will nuclear deterrence be directly involved? Having a shared awareness of these issues and considering them together will forge closer relationships between the U.S. and its allies.

Profile

Born in the U.S. After serving as a member of the research staff at the Institute for Defense Analyses and other institutions was Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Nuclear and Missile Defense Policy from April 2009 through March 2013. Has been a consulting professor at Stanford University till December 2014.

An interview with Hans Kristensen, nuclear strategy expert

Declaration of intent by Japan essential to halting nuclear arms race

The following are edited excerpts from an interview with Hans Kristensen, a nuclear strategy expert, who stresses that Japan’s voice is critical in the effort to halt the nuclear arms race in the 21st Century.

How do you assess the six years of the Obama administration?

Obama will be remembered more for modernizing nuclear weapons than for reducing nuclear weapons. He has been a disappointment.

In terms of nuclear disarmament, it was all he could do to work out the nuclear arms reduction treaty [New START] with Russia. Now, although the U.S. would never think of conducting an underground nuclear test, there is no prospect of the Senate ratifying the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty.

Clearly the president has had to compromise. In particular, as a Democratic president, he has been pressured to embody the concept of a strong America. And he has a bitter adversarial relationship with Congress.

What about his pledge to reduce the role of nuclear weapons?

As long as you define nuclear weapons as weapons to be used not only in response to an enemy nuclear attack but as weapons that are also useful for deterring attacks by conventional weapons, the numbers can’t be greatly reduced. The key is limiting their role. But the “Report on Nuclear Employment Strategy” that the Defense Department issued in June 2013 basically retained the conventional nuclear plan from the days of the Cold War between the U.S. and the Soviet Union.

If program is to be halted, it must be done now

Is there no change in the trend to increase the budget for nuclear weapons either?

If you look at the budget request for the 2016 fiscal year, which was submitted in early February, it is even clearer. But in the U.S. it’s the legislature – not the executive branch – that has the authority to prepare the budget, so things won’t go that way. The federal government’s expenditures for fiscal reconstruction have recently been subject to mandatory reductions. In that sense, the legislature’s moves will be called into question.

Are there items Hiroshima should be paying attention to?

There are a lot of things, but, to give one example, the plan for the Air Force’s long-range standoff [LRSO] weapons to be deployed on the next-generation long-range bombers. Congress has cut the budget for this project for three years in a row, but the Obama administration has proposed a budget of $36 million, ten times that of the previous fiscal year. That’s not a significant amount, but the intent of the Obama administration can be seen.

The LRSO is only in the study phase, not the engineering phase. Improvements to the existing W80-1 nuclear warhead have yet to be made either. If an effort to halt development is to be made, now is the time. By the 2020s it will be too late.

I’ve heard that along with nuclear warheads the cost will be $30 billion.

Seen from the standpoint of the make-up of U.S. nuclear capability, it can only be regarded as completely redundant. While pointing at northeast Asia on a world map, an Air Force official told me that it was for extended deterrence. That means Japan and South Korea. The U.S. has interested parties who, while broaching the idea of Japan arming itself with nuclear weapons, use that as leverage to increase their budget.

Danger of secret meetings

There’s a gap between the thinking of the people of Hiroshima and the Japanese government. I wonder which is being heard by the U.S. administration.

In that sense, I’m concerned about the Japan-U.S. Extended Deterrence Dialogue. To what extent are they sharing information on the U.S. nuclear strategy? What intent is Japan conveying? Very little information has gotten out.

Insofar as possible, the decision-making process for policy should be transparent and should be verified. The lesson of the so-called “secret nuclear pact” between Japan and the U.S. is the danger of secret meetings between a handful of people from both governments. We must learn from history.

It isn’t easy, but it’s important to focus on the issues at hand and try to nip problems in the bud. It will be difficult to achieve this by just focusing on the goal of eliminating nuclear weapons. I’d like people to realize that a declaration of intent by Japan has even more impact on the U.S. than is thought to be the case in Hiroshima.

Profile

Born in Denmark in 1961. Previously worked for non-governmental organizations, including the international environmental organization Greenpeace. Now serves as director of the Nuclear Information Project at the Federation of American Scientists. Leading researcher on nuclear capability. Calls for the disclosure of information, and data he has compiled that draws on his own research has been published in the yearbook of the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute and other publications and is often cited. This includes data on the number of nuclear weapons countries possess and the make-up of their nuclear capability.

President Obama and U.S. Nuclear Policy

Jan. 2007

Four former top administration officials submit a letter titled “A World Free of Nuclear Weapons” to The Wall Street Journal

Oct. 2007

Prior to the presidential primary election, Democratic candidate Barack Obama gives a foreign policy speech at DePaul University in Chicago in which he says, “America seeks a world in which there are no nuclear weapons.”

Nov. 2008

Elected president

Jan. 2009

Inaugurated

April 2009

Delivers speech in Prague declaring “America's commitment to seek the peace and security of a world without nuclear weapons”

Sept. 2009

Serves as chairman of the U.N. Security Council summit on nuclear disarmament and non-proliferation, resolution “to create the conditions for a world without nuclear weapons” unanimously adopted

Dec. 2009

Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START I) between U.S. and Russia expires with no new agreement in place

Obama awarded Nobel Peace Prize

April 2010

Nuclear Posture Review outlining administration’s stance on nuclear policy formulated; while calling for “reducing the number of nuclear weapons and their role in U.S. national security strategy” it takes no bold steps U.S., Russia sign New START (successor to START I)

Sept. 2010

Administration’s first subcritical nuclear test

Dec. 2010

U.S. Senate ratifies New START

Nov. 2012

Obama re-elected president

June 2013

In a speech in Berlin, Obama says, “Because of the New START Treaty, we’re on track to cut American and Russian deployed nuclear warheads to their lowest levels since the 1950s” and adds that security can be ensured “while reducing our deployed strategic nuclear weapons by up to one-third.”

Defense Department releases its “Report on Nuclear Employment Strategy of the United States”; while stating that the U.S. “seeks the peace and security of a world without nuclear weapons” it also stresses the need to maintain nuclear deterrence

Highlights of Obama’s Prague Speech

•“As a nuclear power, as the only nuclear power to have used a nuclear weapon, the United States has a moral responsibility to act. We cannot succeed in this endeavor alone, but we can lead it, we can start it.”

•“So today, I state clearly and with conviction America's commitment to seek the peace and security of a world without nuclear weapons.”

•“This goal will not be reached quickly –- perhaps not in my lifetime.”

•“To put an end to Cold War thinking, we will reduce the role of nuclear weapons in our national security strategy, and urge others to do the same.”

•“As long as these weapons exist, the United States will maintain a safe, secure and effective arsenal to deter any adversary, and guarantee that defense to our allies.”

•“So today I am announcing a new international effort to secure all vulnerable nuclear material around the world within four years.”

Keywords

Nuclear Umbrella

“Nuclear umbrella” refers to a concept by which the U.S. guarantees the safety of Japan and other allies with nuclear weapons. By being prepared to retaliate with its nuclear capability at any time, the U.S. discourages enemies from attacking its allies. With the Soviet Union and China during the Cold War – and later North Korea – as the presumed enemies, the U.S. has offered the protection of its nuclear umbrella to Japan. The concept of providing security to U.S. allies through the nation’s overall military strength, including conventional weapons, not just nuclear weapons, is referred to as “extended deterrence.”

NATO and nuclear weapons

The U.S. also offers the protection of its nuclear umbrella to member nations of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). In addition to strategic nuclear weapons, a total of 200 nuclear bombs out of the 500 tactical nuclear weapons possessed by the U.S. are deployed in Belgium, the Netherlands, Germany, Italy and Turkey. A legacy from the days of preparation against attack by the Soviet Union, this policy is referred to as “nuclear sharing.” Under this policy all of these nations except Turkey are prepared for their military aircraft to use these weapons in an emergency. Nuclear sharing has been criticized as a violation of the Nuclear Non-proliferation Treaty, which stipulates an obligation not to transfer nuclear weapons.

In 1966 NATO established a Nuclear Planning Group. With the exception of France, which attaches importance to the independence of its nuclear capability, 27 member nations attend regular meetings of the group at which they discuss policies for the deployment and use of NATO’s nuclear capability.

Extending life of nuclear warheads, prospects for abolition remote

■ Kansas City: financial gain from nuclear weapons “unacceptable”

A sign at the gate says “National Security Campus,” calling up images of a leafy college campus. A walking trail traverses the perimeter of the facility’s grounds.

Move from aging facility to new one

Kansas City, Missouri, a Midwestern city known for jazz, has a population of 450,000. On its outskirts lies a facility charged with the maintenance of the nation’s nuclear warheads. The facility handles weapons such as W76 nuclear warheads, which are designed for launch from strategic nuclear submarines, replacing aging internal parts. This extends the useful life of the nuclear warheads by another few decades.

The functions of the aging former facility, which went into operation in the 1940s, were transferred to the new facility in August of last year. The facility is operated by Honeywell International, Inc., a multinational corporation, under a contract with the government. According to a press release, the facility is about three times the size of a baseball stadium and employs about 2,700 people.

Ann Suellentrop, a local peace activist, noted that her area was profiting from weapons of mass destruction and nuclear abolition seemed further and further away. She said nuclear weapons were also unacceptable on ethical grounds.

While the facility was under construction, she and other members of a pacifist organization as well as local lawyers held non-violent protests. A total of 120 protesters were arrested for illegally venturing onto the facility’s premises, but nevertheless they were unable to prevent the implementation of a plan that was approved during the administration of President George W. Bush.

Ms. Suellentrop, a nurse in the newborn nursery at a general hospital, comes in contact with new life every day. A devout Catholic, she believes that nuclear weapons, which kill large numbers of people indiscriminately, are incompatible with the Christian teachings of respect for life and peace.

Around August 6 every year she and other activists gather in a park in downtown Kansas City and float lanterns on a popular pond, recalling Hiroshima and Nagasaki and renewing their vow to continue to tell of the savagery of nuclear weapons.

“What was the Peace Prize all about?”

President Barack Obama delivered his historic speech in Prague, the Czech Republic, in April 2009.

Scott Kovac, 58, is operations and research director for Nuclear Watch New Mexico, which is based in Santa Fe. Santa Fe is about one hour away by car from the Los Alamos National Laboratory, the site of the development of the atomic bomb. Mr. Kovac said the members of his group had hoped the president would take more action and they wondered why he received the Nobel Peace Prize. He said he suspected the people of Hiroshima must have felt the same.

A Waste Isolation Pilot Plant (WIPP) in southern New Mexico carries out the underground disposal of radioactive waste. In February of last year, a drum from Los Alamos that had been brought to the plant burst as the result of a chemical reaction by the contents. Some workers were exposed to radiation as a result, and radioactive materials were released into the atmosphere. The facility has remained closed since then. As a result of this incident, people were once again reminded of the cost to health and environment of maintaining the nation’s nuclear weapons.

Mr. Kovac said with evident frustration that, seen from another perspective, the U.S. had not changed under President Obama and in fact he had been a disappointment.

Current U.S. policy, plans for expanded budget

More than $348 billion in 10 years

After his inauguration as president, Barack Obama made a speech in which he called for “reducing the number of nuclear weapons and their role in U.S. national security strategy.” His predecessor, George W. Bush, had been embarking on the development of a new nuclear warhead and was not cooperative with the international nuclear non-proliferation regime. So President Obama acquired a sharply contrasting image both at home and abroad.

Jon Wolfsthal, 48, served as a special advisor for Nonproliferation and Nuclear Security in the office of the Vice President during President Obama’s first term. He agreed to be interviewed in Washington in December of last year before becoming Senior Director for Arms Control and Nonproliferation at the National Security Council (NSC). Mr. Wolfsthal pointed out, however, that decisions on nuclear policy that have been made under the two administrations are not very different.

He noted that while the Bush administration put priority on acquiring huge amounts of money to finance the Iraq war, it limited the amount of money that went to the nuclear weapons enterprise. But under the Obama administration, expenses have continued to balloon, seemingly in an effort to restore them to their former level.

The life extension program (LEP) for the refurbishment of nuclear warheads that have been in existence since the Cold War, the development of missiles to launch nuclear warheads and the replacement of strategic nuclear submarines that are nearing retirement – these plans to completely modernize the nation’s nuclear weapons systems are all awaiting implementation. The renovation of infrastructure like that in Kansas City is no exception.

According to a report issued by the Congressional Budget Office in January, if the plans formulated by the Defense and Energy departments are implemented, a total of $348 billion is expected to be needed over 10 years from fiscal year 2015. Another report prepared for Congress estimates that the maintenance of the nation’s strategic nuclear weapons will cost $1 trillion over the next 30 years.

If the U.S. were to give up possessing nuclear weapons, there would be no maintenance costs. But in his Prague speech President Obama said, “As long as these weapons exist, the United States will maintain a safe, secure and effective arsenal to deter any adversary, and guarantee that defense to our allies.” It appears as if the administration has focused on carrying this out.

Linton Brooks, 76, served in the Bush administration for five years from 2002 as Under Secretary of Energy for Nuclear Security and Administrator of the National Nuclear Security Administration. He stressed that it is essential to work to maintain the safety and reliability of nuclear weapons from the Cold War era. Mr. Brooks played a leading role in the plan to develop the Reliable Replacement Warhead (RRW), a new nuclear warhead, but this effort was frustrated by Congressional opposition.

While asserting that the pursuit of “a world without nuclear weapons” would put the world in danger by triggering war with conventional weapons, Mr. Brooks also had praise for President Obama. He said that the LEP situation has some elements in common with the RRW and noted that while he had had political failures, some of his ideas have been taken up by the Obama administration.

But President Obama has declared that the U.S. will not develop new nuclear warheads. When asked about that, Mr. Brooks replied with an analogy using classic cars, noting that they remain classic cars even if their tires or some parts are replaced.

The global nuclear arms race is shifting from an emphasis on the quantity of nuclear warheads and delivery devices to exploiting technology to improve quality. Russia and China also aspire to modernize their nuclear weapons, and North Korea is moving forward with the miniaturization of warheads and the development of missiles. But the overwhelming supremacy of the U.S. remains unquestioned. The obligation of nuclear disarmament set forth in the Nuclear Non-proliferation Treaty may become a dead letter.

Resistance to decline in military potential behind setbacks

Disarmament negotiations with Russia stalled

Amid ballooning budgets for nuclear weapons and no decline in their number, how do those who were involved with the Obama administration and experts on nuclear disarmament and non-proliferation view the current situation?

Daryl Kimball, 50, executive director of the Washington-based Arms Control Association, said that a new nuclear arms reduction treaty with Russia had clearly triggered concessions by the president.

The previous treaty, START I, expired in 2009. A new treaty was a high-priority issue for the administration in order to avoid giving Russia free rein in terms of its nuclear arsenal. But ratification of a treaty requires the approval of two thirds of the U.S. Senate. Conservatives in the legislature stressed that the new treaty would weaken the nation’s nuclear capability and sought to make a bigger budget for nuclear weapons part of administration policy. Mr. Kimball said that considering the domestic situation, it was impossible to pin all of one’s hopes on the president.

Politicians, bureaucrats and business people involved in the maintenance of nuclear weapons apparently take a dim view of the notion of a world without nuclear weapons.

James Doyle, 56, is a former nuclear safeguards and security policy specialist at Los Alamos National Laboratory. Two years ago, while working at the laboratory, he submitted an article titled “Why Eliminate Nuclear Weapons?” to a well-known British journal that deals with security issues. In his article he said that “giving up nuclear weapons…may indeed lead to a safer world” and referred to the ideology of nuclear deterrence as a “myth.” Several days after the article was published Mr. Doyle was told by his supervisor that, although officials had reviewed the article before publication, the content was classified. Mr. Doyle was later fired.

But the article can still be read on line. Some people believe that, as the article called for the abolition of nuclear weapons, it incurred the wrath of legislators and the laboratory over-reacted.

Gary Samore, 61, served as White House Coordinator for Arms Control and Weapons of Mass Destruction under President Obama and led the Nuclear Security Summit that was held at the urging of the president. According to Mr. Samore, the administration has troubles both at home and abroad. One key point of the president’s speech in Prague was this declaration: “So today I am announcing a new international effort to secure all vulnerable nuclear material around the world within four years.” The reference to international cooperation elicited a positive response, but Mr. Samore noted that disarmament has its limits. He pointed out that Russian President Vladimir Putin had a negative attitude toward nuclear disarmament and said that with relations between the U.S. and Russia chilly on account of the Ukraine issue, further negotiations on nuclear disarmament were unlikely any time soon.

Two years into his second term, citing a need to leave a legacy to future generations, President Obama directed the restoration of diplomatic relations with Cuba, with which the U.S. has had a long-standing conflict. Many people in Hiroshima would like to see the president once again take up the pledge he made in his speech in Prague and renew in Hiroshima his resolve to bring about a world without nuclear weapons.

Five years ago, Tadatoshi Akiba, then mayor of Hiroshima, met with President Obama at the White House along with a group from the U.S. Conference of Mayors. At that time Jon Wolfsthal, a special advisor for Nonproliferation and Nuclear Security in the office of the Vice President, was also present. Mr. Wolfstahl said that the president was well aware of the invitation to visit Hiroshima but that such a visit could only be made when it was deemed to be clearly in the interest of the nation to do so.

U.S. Nuclear Weapons

Nuclear warheads 7,300

Intercontinental ballistic missiles 450

Strategic nuclear submarines 14

Ballistic missiles on nuclear submarines 288

Long-range bombers with nuclear missions 60

Other Countries’ Nuclear Warheads

Russia 8,000

U.K. 225

France 300

China 250

India 90-110

Pakistan 100-120

Israel 80

North Korea 6-8

(Estimates provided by Hans Kristensen)

Keywords

Strategic and tactical nuclear weapons

Strategic nuclear weapons are long-range nuclear weapons that consist of nuclear warheads mounted on intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBM) and other missiles. The nuclear arms reduction treaty with Russia (New START) sets upper limits on the number of ICBMs at underground sites in the U.S. and ballistic missiles deployed for launch from submarines as well as long-range bombers and the nuclear warheads they carry.

Tactical nuclear weapons, on the other hand, are manufactured for use in war and have a short range. The U.S. has approximately 500 nuclear bombs. Russia is believed to have 2,000, but there have been no negotiations on reductions in tactical nuclear weapons.

Maintenance of U.S. nuclear weapons

The Atomic Energy Commission, a predecessor of the U.S. Department of Energy, produced and developed a large number of nuclear warheads during the Cold War. Today the National Nuclear Security Administration, an agency under the Energy Department, maintains nuclear weapons under its Stockpile Stewardship and Management Program. It also has jurisdiction over national laboratories that have designed and developed nuclear warheads.

The Department of Defense is primarily involved in the development and deployment of weapons that can launch nuclear warheads. ICBMs, strategic nuclear submarines and their ballistic missiles, and long-range bombers are referred to as the three main delivery devices for strategic nuclear weapons. Because the cost of maintaining and updating these weapons is substantial, some people have called for large reductions in their numbers and the elimination of ICBMs, but the Obama administration has decided to maintain them.

(Originally published on February 14, 2015)