Hiroshima Asks: Toward the 70th Anniversary of the Atomic Bombing: Denuclearizing Northeast Asia

Jun. 19, 2015

by Masakazu Domen and Yumi Kanazaki, Staff Writers

Facing North Korea and its nuclear arsenal, South Korea continues to rely on the U.S. umbrella for its security, like Japan. A number of South Koreans are A-bomb survivors because they were in Hiroshima or Nagasaki back then, when Japan colonized the Korean Peninsula. Relations between Japan and South Korea have cooled recently over differences in perceptions of history. How can a more cooperative relationship be built to advance the abolition of nuclear weapons? The Chugoku Shimbun considers remedies in this article, eyeing the establishment of a nuclear-weapon-free zone in Northeast Asia.

Loud shouts echoed from a street in Ginza, Tokyo. A group of 40 people marched down the pavement with a banner in their hands. “Kick out Koreans!” it read. Though they raised issues involving disputed islands and the “comfort women,” this was standard hate speech along racial lines. Some marchers also held a sign listing the “three non-Korean principles,” such as the “non-introduction of Koreans to Japan,” a satiric slur of Japan’s three non-nuclear principles.

Along the route, a mass of people had gathered to protest the march. To prevent a clash between the two sides, the police surrounded the marchers on all sides. A 45-year-old woman who was there to protest expressed outrage. “This is going too far,” she said. “It tears apart our relationship with the Korean residents of Japan and the people of neighboring countries.”

Worried about hate speech

Since around 2013, hate speech has become a marked social issue in Japan, taking place more frequently and growing more radical. Shin Hyung-keun, the former South Korean consul general in Hiroshima, said, “I want to believe this is just a temporary phenomenon, but it worries me because it seems to be an attempt to have the Japanese people ignore the ‘negative history’ of colonial rule and war.”

A relief movement pursued by A-bomb survivors in South Korea, including his father, Shin Yong-su, was supported by Japanese people who faced up to this negative legacy and sought to overcome it. Mr. Shin said, “If this spirit is lost, it will be impossible for Koreans to stress the inhumanity of nuclear weapons to the world, along with the Japanese, beyond national borders. Then, the goal of abolishing nuclear arms, which my father genuinely hoped for, would be out of reach.”

Shin Yong-su came to Japan in 1942, during the war. In 1945, while working for an army-affiliated pharmaceutical company in Hiroshima and feeling fortunate to be employed, he experienced the atomic bombing at a streetcar stop about 1.2 kilometers from the hypocenter. Mr. Shin suffered severe burns to his face and other parts of his body and returned to Korea. In 1967, he helped found the initial version of the South Korean Atomic Bomb Sufferers Association. In 1974, while visiting Japan for medical treatment, he obtained the Atomic Bomb Survivor’s Certificate, the first A-bomb survivor living in South Korea to do so.

Impressed with dedication of Japanese

Shin Hyung-keun scorns Japan’s colonial rule, which brought about the atomic bombing and his father’s injuries. At the same time, as he met the Japanese people who lent support to his father’s campaign, he was deeply impressed. Looking back, Mr. Shin said, “The dedication of the Japanese supporters helped produce the current relief standards for South Korean A-bomb survivors. Though, at first, both the Japanese government and the Korean government wouldn’t respond, the survivors gained their rights through legal action.”

After Mr. Shin began serving as the South Korean consul general in Hiroshima, he compiled the history of his father’s activities as his doctoral dissertation at the graduate school of Hiroshima University. His research was focused on grassroots cooperation between citizens in Japan and South Korea. “I’d like the Japanese people to know that a great many efforts were made by Japanese and Koreans in the past to address issues involving A-bomb survivors and there have been significant developments concerning relief measures for Korean survivors as well as survivors living outside of Japan. I want to hand down these facts to the people of South Korea, too. I hope that the historical cooperation between the citizens of our two nations will not be soured by actions driven by fleeting emotions,” he said.

After leaving his diplomatic post last summer, Mr. Shin now works as an advisor for the Seoul office of a Chinese trading company. As a former diplomat who served as consul general in Qindao and Shenyang in China, as well as in Hiroshima, he fervently wishes for an end to the Cold War framework in Northeast Asia and the establishment of peace.

Traveling only about 50 kilometers from the center of Seoul, where Mr. Shin’s office is located, you arrive at Imjingak, Paju. From there is a commanding view of the area near the military border with North Korea. Many ribbons have been tied to the barbed wire fences near the 38th parallel, expressing the wish for the peaceful unification of the Korean Peninsula.

With North Korea holding nuclear weapons to shore up its political system, how can it be convinced to abandon its nuclear arsenal? And how should we respond to China’s growing military might, as it seeks to strengthen its nuclear forces? While Mr. Shin said he was unable to offer a quick response to these questions, he made the following comment with conviction:

“It’s vital that both Japan, the A-bombed nation, and South Korea, which can be considered the second A-bombed nation from the perspective of its many survivors, refrain from pursuing their own nuclear arsenals and avoid raising tensions in the region. I believe we can find a way out if we look closely at the ‘positive history’ we share, where the citizens of our two nations have worked together to move the attitude of our governments.”

--------------------

What would happen if a nuclear-armed missile reached Seoul, the capital of South Korea? At the War Memorial of Korea, which has a high profile in Seoul, there is a section which considers this threat posed by nuclear weapons.

This museum focuses on the history of the Korean War and many of its visitors are students. One boy, 13, from a junior high school in Seoul, said, “I was surprised to learn that even a single missile could cause widespread damage in Seoul.” Another boy, also 13, said, “I don’t think South Korea should possess nuclear weapons. But I’m worried whether the United States will protect us forever.”

In 2006, North Korea announced its first successful underground nuclear test. Without nuclear weapons of its own, and a party to the Nuclear Non-proliferation Treaty (NPT), South Korea has had to stare down North Korea since the two sides agreed to a ceasefire. Meanwhile, the U.S. military removed its tactical nuclear weapons from South Korea in 1991. The nuclear developments in North Korea continue to impact public opinion and policies in South Korea as well as in Japan.

In February 2013, North Korea conducted its third nuclear test. Immediately following the test, the Asian Institute for Policy Studies, a private think tank in South Korea, conducted a survey of 1,000 South Korean men and women aged 19 and over. According to the survey, 66.5 percent of the respondents agreed with the idea of South Korea arming itself with nuclear weapons to compete with North Korea. Kim Jiyoon, 43, the director of the survey, explained the result, saying, “The younger the respondents are, the more they’re opposed to holding nuclear weapons. Still, 50 percent of those less than 30 years old indicated support for the idea.” In another survey conducted in July 2014, a total of 52.7 percent of the respondents were in favor.

Is it possible that public opinion in South Korea could overturn the government’s non-nuclear stance? Han Yongsup, 59, a professor at the Korean National Defense University who previously was responsible for nuclear policy in the Ministry of National Defense, believes, “The alliance between South Korea and the United States is strong, so it isn’t likely that South Korea would dare leave the NPT and develop nuclear weapons. As the public is well aware of the fatigue in North Korea’s capacity as a nation, South Koreans won’t pursue such an extreme course.”

Instead, Mr. Han warns about the view of South Korean citizens toward Japan. He said, “In South Korea, there are suspicions over the large amount of plutonium held by Japan, which, in spite of its three non-nuclear principles, could be used to develop nuclear weapons.”

In June 2014, when the Japanese government reported on Japan’s stockpile of plutonium to the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), it failed to include 640 kilograms of plutonium, contained within spent fuel as a result of the accident at the Fukushima No. 1 (Daiichi) nuclear power plant. The media in Japan termed this an “omission,” but in South Korea, the media eyed this with suspicion, wondering whether Japan was in fact contemplating nuclear armament.

Jeon Jinho, 52, a professor at Kwangwoon University and an expert on the nuclear policies of Japan and South Korea, said, “In South Korea, which is competing with Japan over exports of nuclear power plant technology, there is increasing support for the idea of initiating the nuclear fuel cycle and stockpiling plutonium.” In fact, regulations on this point were partially eased in the revised nuclear agreement between South Korea and the United States, completed on April 22.

While under the U.S. nuclear umbrella, neither Japan nor South Korea have sought to hold their own nuclear arms. But with bilateral relations between these two nations at a low ebb, the denuclearization of Northeast Asia could become a more distant dream if they eye one other with rising suspicion over their nuclear policies.

--------------------

How can the citizens of Japan and South Korea work together to advance a world free of nuclear weapons? The Chugoku Shimbun interviewed Keisaburo Toyonaga, 79, the director of the Hiroshima branch of the “Association of Citizens for the Support of South Korean Atomic Bomb Victims,” and Kim Yeong Hwan, 42, the head of the external cooperation team of the Institute for Research in Collaborationist Activities, which specializes in studies of modern Korean history from the perspective of its relations with Japan.

Keisaburo Toyonaga, director of the Hiroshima branch of the Association of Citizens for the Support of South Korean Atomic Bomb Victims: Youth should engage in frank exchange

I have a connection with a youth group in the city of Daegu, South Korea. Five years ago, I lent support for their exhibition about the atomic bombings. When I went to see it, I was surprised because the exhibition was held along the corridor of a subway station. I told them that they should rent a hall somewhere so people could get a better look, but they said, “If we did, no one would come and see it. This is the only way to get the public to see the exhibition.”

This made me sharply aware of the large difference between the people of South Korea and the people of Japan when it comes to their interest in the A-bomb damage. On the other hand, these young people in South Korea showed real commitment in their diligent efforts to find a location that would give people the chance to learn more about the atomic bombings.

My activities in this area were prompted by an unexpected encounter. When I was a high school teacher in 1971, I was staying at a hotel the day before I went to South Korea for a training course. When I was watching TV at the hotel, I saw A-bomb survivors in South Korea on TV. I was shocked and I searched them out when I had time during my training.

I was appalled by the fact that these survivors weren’t eligible for relief from the Japanese government, so I became a member of a group of supporters and opened a branch here in Hiroshima. Since that time I have lent support to many lawsuits over this issue and I believe we were able to gain the understanding of many people for our campaign and move forward by positioning the problem as an issue of universal human rights: “A-bomb survivors are the same, no matter where they live.” I think the same goes for current discussions on the inhumanity of nuclear weapons, intended to advance nuclear disarmament worldwide.

The worsening relationship between Japan and South Korea concerns me, but I have hopes for the youth of both countries because young people can consider nuclear issues from the point of view of human rights. In South Korea, the older generation, with their vivid memory of Japan’s colonial rule, sees the atomic bombings as acts of liberation. The younger generation, though, doesn’t share this same perspective. If the young people of our two countries spoke frankly and shared their views on historical perceptions and other issues, I’m confident that such discussion would produce positive results.

In South Korea, the issue of the A-bomb survivors is often viewed in the context of the unresolved postwar compensation from Japan, as well as the issue of the comfort women. There are far fewer opportunities for A-bomb survivors in South Korea to share their accounts, as messengers conveying the threat of nuclear weapons, compared to survivors in Japan.

Most South Koreans are predominantly concerned about the comfort women. I’m afraid they don’t show much interest in nuclear disarmament or nuclear abolition. They are also opposed to the idea of the Japanese thinking of themselves as victims, which gets emphasized when talk turns to the A-bomb damage.

However, I believe the number of people who view the bombings in a positive light, as an image of liberation from Japan’s colonial rule, has declined. Facing the threat of North Korea’s nuclear weapons, the people of South Korea have become more aware of the horrific damage caused by nuclear weapons. In South Korea, second-generation A-bomb survivors have launched a campaign for relief measures, which I support. There is now a foundation for antinuclear activities. If there can be collaboration with efforts in Japan, the movement will grow.

At the same time, I’m concerned that the problem of historical perceptions may be an obstacle to progress. The attitudes of the governments of Japan, headed by Shinzo Abe, and Korea, led by Park Geun-hye, may make things worse. The influence of these attitudes must be minimized and the citizens of both countries must work together to influence their governments.

When I was 25 years old, I took part in a joint Japan-South Korea project to unearth the remains of Korean nationals who were forced to labor in the construction of dams and railways in Hokkaido and died during the war. Since that time, based on the bond I developed with Japanese people in that project, I have continued my peace activities, traveling back and forth from South Korea to Japan. I believe we can make progress on the major goal of abolishing nuclear weapons, step by step, by promoting personal interaction and ties of friendship.

--------------------

Over the past nine years, North Korea has stubbornly pursued three nuclear tests. Russia revealed a reliance on its nuclear arsenal in connection with the crisis in Ukraine. China has been criticized for a lack of transparency regarding its nuclear weapons. Surrounded by these nations, Japan and South Korea have clung to the U.S. nuclear umbrella.

Seeing the current state of affairs in Northeast Asia, the road toward nuclear abolition looks bleak. The six-party talks to discuss North Korea’s nuclear issues remain at an impasse.

Seeking solutions, in April Nagasaki University’s Research Center for Nuclear Weapons Abolition (RECNA) announced its recommendation to establish a nuclear-weapon-free zone in Northeast Asia.

Appeal for proposal at NPT Review Conference

“If we only ask North Korea to denuclearize, nothing will happen. We should change our mindset to ease tensions in the region by negotiating a nuclear-weapon-free zone with the other nations that are involved,” stressed Tatsujiro Suzuki, 64, the new director of RECNA, who assumed his post from his predecessor, Hiromichi Umebayashi.

Mr. Suzuki continued, “I would like to strongly convey this recommendation as a proposal which originates from an A-bombed city.” RECNA will hold a gathering at this year’s Review Conference of the Nuclear Non-proliferation Treaty (NPT), opening on April 27, and appeal for the recommendation to the 190 NPT member nations. Mr. Suzuki is now busy making preparations for this effort with RECNA staff, including Keiko Nakamura, 42, an associate professor who will accompany him.

The recommendation is a “three-plus-three” proposal, which indicates the number of nations involved. The idea is that the first three countries--Japan, South Korea, and North Korea--will affirm that they won’t possess nuclear weapons while the other three countries--the United States, Russia, and China--will commit to not attacking or threatening the first three nations with nuclear weapons. The goal of the recommendation is to conclude a treaty. To realize this aim, the recommendation also urges a formal end to the Korean War, which even today remains under ceasefire conditions, and a “comprehensive framework agreement” for establishing ongoing conferences to discuss security issues.

Since the founding of RECNA at Nagasaki University three years ago, former senior government officials and security experts from these six nations, and RECNA staff, have held a series of discussions. The Hiroshima Peace Institute at Hiroshima City University has lent its support to this initiative and co-hosted RECNA’s international workshop. Efforts to flesh out and enact details of the recommendation will continue this year and beyond.

Whether this concept can be realized as actual policy depends on response of the Japanese government. After the recommendation was released, Mr. Suzuki and his staff visited the Ministry of Foreign Affairs on April 10 and requested that the government adopt this blueprint. Mr. Suzuki felt that some appreciation was given for the fact that the recommendation not only appeals for denuclearization, but also takes further steps by proposing “the path forward.” However, the Japanese government, which relies on U.S. nuclear deterrence, finds it difficult to pursue this path and attain the state where the nations of Northeast Asia no longer depend on nuclear arms to ensure security.

Underlying support from the public is crucial

“A nuclear-weapon-free zone could contribute to Japan’s security. Japan and South Korea should take the lead, with the Japanese leadership, in particular, seeking a breakthrough.” The Chugoku Shimbun spoke to Morton Halperin in Washington D.C. last December. Mr. Halperin is a former senior government official who had a range of key responsibilities for the United States. He strongly supports the idea of a nuclear-weapon-free zone in Northeast Asia. In fact, Mr. Halperin’s endorsement of RECNA’s recommendation lent momentum to the effort because he has extensive knowledge of U.S. nuclear strategy and the Japan-U.S. alliance.

Mr. Halperin said, “If Japan makes clear that it will never possess nuclear weapons and seeks the denuclearization of the region, South Korea will have no choice but to follow suit,” he said. “It would also eliminate skepticism over the question of South Korea assuming control over North Korea’s nuclear weapons when the Korean Peninsula is unified. China and Russia would welcome this as well.”

In 2010, the Obama administration announced that the United States would not use, or threaten to use, nuclear weapons against non-nuclear weapon states which abide by the NPT. Though current conditions don’t lend themselves to negotiations with North Korea, Mr. Halperin said with certainty, “The United States is also ready to accept the idea of a nuclear-weapon-free zone in Northeast Asia.”

How far will this proposal from an A-bombed city, based on existing nuclear-weapon-free zones in other regions of the world, be carried? Clearly, the underlying support from the broader public, with their hopes for nuclear abolition and regional peace, is crucial.

--------------------

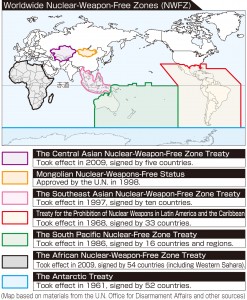

In a nuclear-weapon-free zone, the countries of a given region pledge not to produce, obtain, or deploy nuclear weapons. Nuclear powers that are members of the NPT are obliged not to threaten or attack countries in a nuclear-weapon-free zone with their nuclear arms. Countries in these zones are required to conclude a treaty and comply with its principles.

The Antarctic Treaty, which took effect in 1961 and stipulates the peaceful use of Antarctica, is a precedent. The impetus for the first nuclear-weapon-free zone, established in Central and South America in 1968, was the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962, when the United States and the former Soviet Union came to the brink of nuclear war. Then, against the backdrop of regional issues, nuclear-weapon-free zones were established in other regions, such as the South Pacific Ocean area, which suffered serious damage as a consequence of nuclear tests conducted by the United States and other countries. In the northern hemisphere, Mongolia, enclosed by Russia and China, has sought to preserve its security by announcing its status as a single-state nuclear-weapon-free zone.

Meanwhile, some other regions have considered establishing a nuclear-weapon-free zone, but this goal has not yet materialized because one nation continues to pursue the development of nuclear arms despite opposition from its neighbors as well as adversarial relations between the countries concerned. Examples are the Middle East region, which includes Israel, a de facto nuclear weapon state outside the NPT framework, and the Northeast Asian region, which includes North Korea.

With regard to Northeast Asia, many versions of a nuclear-weapon-free zone have been proposed. In 2008, the Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ) prepared a draft treaty, an effort spearheaded by Katsuya Okada, the deputy leader of the DPJ at that time. However, a document titled “Japan’s Efforts on Disarmament and Non-Proliferation,” which was issued by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan in 2013, acknowledges that Japan isn’t prepared to advance a nuclear-weapon-free zone for the region, given the current state of China’s nuclear and conventional military forces.

Meanwhile, the nuclear-weapon-free areas of the world have expanded to include more than 100 countries, covering a large part of the southern hemisphere. In some cases, the feeling of momentum to establish a nuclear-weapon-free zone and the series of subsequent discussions among the countries concerned fostered mutual trust within the region and led to willingness to abandon nuclear arms. One example is South Africa, which had been secretly pursuing nuclear weapons development. And though Kazakhstan was once home to nuclear weapons on its territory, following the collapse of the Soviet Union, it completely denuclearized. Similarly, in South America, Brazil and Argentina have overcome divisions through dialogue that was prompted by interest in establishing a nuclear-weapon-free zone in the region.

The call for a nuclear weapons convention is now growing in the international community. But outlawing nuclear arms is difficult when nuclear-weapon-free zones have not yet spread worldwide. Moving both efforts forward is a means of achieving international security without relying on nuclear weapons, and eliminating them from the earth.

--------------------

How feasible is the idea of establishing a nuclear-weapon-free zone in Northeast Asia? The Chugoku Shimbun spoke with Hiromichi Umebayashi, a special advisor to Peace Depot, a non-profit organization, and the former first director of the Research Center for Nuclear Weapons Abolition (RECNA) at Nagasaki University. He held this post until March 2015.

When you ended your term at RECNA, you compiled a recommendation for establishing a nuclear-weapon-free zone in Northeast Asia.

Northeast Asia suffers from complex issues involving territory and historical perception, and is very prone to the influence of U.S. policy. But I think it’s possible to independently pursue the theme of denuclearization in this region to important effect. Depending on circumstances, such efforts to advance denuclearization can promote discussion on other issues among countries in the region. I believe this is the challenge we should now pursue.

It seems most people don’t think it’s realistic that North Korea will abandon its nuclear ambitions.

This is the starting point of the discussion. North Korea has repeatedly stated its reason for seeking nuclear weapons. With the United States in mind, they say, “We’re facing a nuclear threat.” North Korea feels a sense of crisis, worried that their regime may be upended by the United States, as in Libya and Iraq.

If they no longer feel threatened by nuclear weapons or military might, there would be no reason for North Korea to maintain a nuclear arsenal. The intent of a nuclear-weapon-free zone is to eliminate nuclear threats from this region in a legally binding manner.

There is growing concern over China’s efforts to strengthen its nuclear capability.

Nuclear weapons in China represent its war-making capability on a global scale. Strengthening its arsenal is intended as a nuclear deterrent, to bolster its ability to retaliate against the United States. To halt this trend, the issue must be addressed along with the nuclear weapons held by the United States and Russia under a worldwide framework of denuclearization, centering on the NPT. There’s no reason, really, for China to strengthen its nuclear capability against the other nations of Northeast Asia, including Japan. I don’t think China’s actions are helpful, but they don’t necessarily make denuclearization more difficult in Northeast Asia.

What actions should Japan pursue?

At the beginning of the action plan that was agreed to at the NPT Review Conference in 2010, it states: “All States parties commit to pursue policies that are fully compatible with the Treaty and the objective of achieving a world without nuclear weapons.” As a country that relies on the U.S. nuclear umbrella, Japan, as well as South Korea, is being tested on its ability to move toward abandoning the nuclear umbrella for its security.

At this year’s Review Conference, we will call for establishing a nuclear-weapon-free zone in Northeast Asia. Subsequently, the six-party talks should be resumed to discuss this theme. We believe these are the actions Japan and South Korea should pursue. Though these two nations have a difficult relationship, they can advance common interests through dialogue.

If movement can be made, this would be a fruitful outcome.

There is skepticism over whether this Review Conference can bring about any meaningful results. With the United States and Russia now at loggerheads, the nuclear weapon states are not likely to propose bold measures. This is why I insist that Japan act to save the NPT. If a nation which relies on nuclear deterrence proposes a new idea, this could have a significant impact.

Profile

Hiromichi Umebayashi

Born in Hyogo Prefecture in 1937, he completed his Ph.D at the graduate school of the University of Tokyo. After working as a university lecturer, he founded Peace Depot, a private nuclear and peace research institute in Yokohama in 1998. He served as the director of RECNA from April 2012 to March 2015.

Major events involving nuclear weapons in Northeast Asia

August 1945

World War II ends.

August 1948

South Korea is established. North Korea is established in September.

August 1949

The Soviet Union conducts its first nuclear test.

June 1950

The Korean War begins. (Ceasefire agreement is reached in July 1953.)

January 1958

The U.S. military begins to deploy tactical nuclear weapons in South Korea.

October 1964

China conducts its first nuclear test.

June 1965

The Treaty on Basic Relations between Japan and South Korea is signed.

January 1968

Prime Minister Eisaku Sato announces the three non-nuclear principles as well as Japan’s reliance on U.S. nuclear deterrence.

March 1970

The Nuclear Non-proliferation Treaty (NPT) takes effect.

November 1971

Japan’s Lower House passes a resolution for the three non-nuclear principles to become national policy.

December 1985

North Korea joins the NPT.

December 1989

U.S. and the Soviet Union declare the end of the Cold War.

September 1991

U.S. President George H.W. Bush announces the removal of nuclear weapons deployed in South Korea.

December 1991

South Korea and North Korea agree to a joint declaration to denuclearize (takes effect in February 1992).

October 1992

Mongolia declares status as a “a one-state nuclear-weapon-free zone.” (U.N. approves it in December 1998.)

March 1993

North Korea announces its withdrawal from NPT regime in reaction to inspection of its nuclear facility. It retracts the announcement in June this same year.

October 1994

U.S. and North Korea sign a framework to freeze North Korea’s nuclear weapons program.

August 1998

North Korea conducts a test launch of the ballistic missile “Taep’o-dong.”

June 2000

First Inter-Korean Summit takes place.

October 2002

North Korea admits having a uranium enrichment plan to U.S.

January 2003

North Korea again announces its withdrawal from NPT. It also renounces the Inspection Convention with IAEA (International Atomic Energy Agency).

August 2003

The six-party talks begin.

February 2005

North Korea formally declares its possession of nuclear weapons.

September 2005

The six-party talks release the first joint statement incorporating denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula.

October 2006

North Korea conducts a nuclear test. The U.N. Security Council adopts a sanction resolution against North Korea.

December 2008

Chief delegates of the six-party talks meet. The meeting collapses over the issue of verifying North Korea’s nuclear activities.

April 2009

North Korea launches a long-range ballistic missile, calling it an “artificial satellite.”

May 2009

North Korea conducts its second nuclear test.

November 2010

North Korea shells Yeonpyeong island in South Korea.

February 2012

U.S. and North Korea agree on return of IAEA inspector and provision of food aid.

February 2013

North Korea conducts its third nuclear test.

April 2013

North Korea’s Standing Committee of the Supreme People’s Assembly adopts “Law on Consolidating the Position of a Nuclear Weapons State.”

September 2013

Mongolian president announces at the U.N. that Mongolia will contribute to establishing a nuclear-weapon-free zone in Northeast Asia.

Keywords

Six-party talks

Six-party talks are the multilateral discussions aimed at denuclearizing the Korean Peninsula. The first meeting was held in August 2003. Taking part are China, which serves as chair, Japan, the U.S., South Korea, Russia, and North Korea. A joint statement specifying that North Korea end its nuclear weapons program was adopted in September 2005. However, at the meeting in December 2008, North Korea objected to the method used to verify its denuclearization, and the talks were suspended. In January 2013, North Korea announced that the joint statement has become “extinct.”

(Originally published on April 25, 2015)

Facing North Korea and its nuclear arsenal, South Korea continues to rely on the U.S. umbrella for its security, like Japan. A number of South Koreans are A-bomb survivors because they were in Hiroshima or Nagasaki back then, when Japan colonized the Korean Peninsula. Relations between Japan and South Korea have cooled recently over differences in perceptions of history. How can a more cooperative relationship be built to advance the abolition of nuclear weapons? The Chugoku Shimbun considers remedies in this article, eyeing the establishment of a nuclear-weapon-free zone in Northeast Asia.

Former South Korean consul general: Grassroots cooperation needed

Loud shouts echoed from a street in Ginza, Tokyo. A group of 40 people marched down the pavement with a banner in their hands. “Kick out Koreans!” it read. Though they raised issues involving disputed islands and the “comfort women,” this was standard hate speech along racial lines. Some marchers also held a sign listing the “three non-Korean principles,” such as the “non-introduction of Koreans to Japan,” a satiric slur of Japan’s three non-nuclear principles.

Along the route, a mass of people had gathered to protest the march. To prevent a clash between the two sides, the police surrounded the marchers on all sides. A 45-year-old woman who was there to protest expressed outrage. “This is going too far,” she said. “It tears apart our relationship with the Korean residents of Japan and the people of neighboring countries.”

Worried about hate speech

Since around 2013, hate speech has become a marked social issue in Japan, taking place more frequently and growing more radical. Shin Hyung-keun, the former South Korean consul general in Hiroshima, said, “I want to believe this is just a temporary phenomenon, but it worries me because it seems to be an attempt to have the Japanese people ignore the ‘negative history’ of colonial rule and war.”

A relief movement pursued by A-bomb survivors in South Korea, including his father, Shin Yong-su, was supported by Japanese people who faced up to this negative legacy and sought to overcome it. Mr. Shin said, “If this spirit is lost, it will be impossible for Koreans to stress the inhumanity of nuclear weapons to the world, along with the Japanese, beyond national borders. Then, the goal of abolishing nuclear arms, which my father genuinely hoped for, would be out of reach.”

Shin Yong-su came to Japan in 1942, during the war. In 1945, while working for an army-affiliated pharmaceutical company in Hiroshima and feeling fortunate to be employed, he experienced the atomic bombing at a streetcar stop about 1.2 kilometers from the hypocenter. Mr. Shin suffered severe burns to his face and other parts of his body and returned to Korea. In 1967, he helped found the initial version of the South Korean Atomic Bomb Sufferers Association. In 1974, while visiting Japan for medical treatment, he obtained the Atomic Bomb Survivor’s Certificate, the first A-bomb survivor living in South Korea to do so.

Impressed with dedication of Japanese

Shin Hyung-keun scorns Japan’s colonial rule, which brought about the atomic bombing and his father’s injuries. At the same time, as he met the Japanese people who lent support to his father’s campaign, he was deeply impressed. Looking back, Mr. Shin said, “The dedication of the Japanese supporters helped produce the current relief standards for South Korean A-bomb survivors. Though, at first, both the Japanese government and the Korean government wouldn’t respond, the survivors gained their rights through legal action.”

After Mr. Shin began serving as the South Korean consul general in Hiroshima, he compiled the history of his father’s activities as his doctoral dissertation at the graduate school of Hiroshima University. His research was focused on grassroots cooperation between citizens in Japan and South Korea. “I’d like the Japanese people to know that a great many efforts were made by Japanese and Koreans in the past to address issues involving A-bomb survivors and there have been significant developments concerning relief measures for Korean survivors as well as survivors living outside of Japan. I want to hand down these facts to the people of South Korea, too. I hope that the historical cooperation between the citizens of our two nations will not be soured by actions driven by fleeting emotions,” he said.

After leaving his diplomatic post last summer, Mr. Shin now works as an advisor for the Seoul office of a Chinese trading company. As a former diplomat who served as consul general in Qindao and Shenyang in China, as well as in Hiroshima, he fervently wishes for an end to the Cold War framework in Northeast Asia and the establishment of peace.

Traveling only about 50 kilometers from the center of Seoul, where Mr. Shin’s office is located, you arrive at Imjingak, Paju. From there is a commanding view of the area near the military border with North Korea. Many ribbons have been tied to the barbed wire fences near the 38th parallel, expressing the wish for the peaceful unification of the Korean Peninsula.

With North Korea holding nuclear weapons to shore up its political system, how can it be convinced to abandon its nuclear arsenal? And how should we respond to China’s growing military might, as it seeks to strengthen its nuclear forces? While Mr. Shin said he was unable to offer a quick response to these questions, he made the following comment with conviction:

“It’s vital that both Japan, the A-bombed nation, and South Korea, which can be considered the second A-bombed nation from the perspective of its many survivors, refrain from pursuing their own nuclear arsenals and avoid raising tensions in the region. I believe we can find a way out if we look closely at the ‘positive history’ we share, where the citizens of our two nations have worked together to move the attitude of our governments.”

--------------------

Public opinion in South Korea: Majority want nuclear arms

What would happen if a nuclear-armed missile reached Seoul, the capital of South Korea? At the War Memorial of Korea, which has a high profile in Seoul, there is a section which considers this threat posed by nuclear weapons.

This museum focuses on the history of the Korean War and many of its visitors are students. One boy, 13, from a junior high school in Seoul, said, “I was surprised to learn that even a single missile could cause widespread damage in Seoul.” Another boy, also 13, said, “I don’t think South Korea should possess nuclear weapons. But I’m worried whether the United States will protect us forever.”

In 2006, North Korea announced its first successful underground nuclear test. Without nuclear weapons of its own, and a party to the Nuclear Non-proliferation Treaty (NPT), South Korea has had to stare down North Korea since the two sides agreed to a ceasefire. Meanwhile, the U.S. military removed its tactical nuclear weapons from South Korea in 1991. The nuclear developments in North Korea continue to impact public opinion and policies in South Korea as well as in Japan.

In February 2013, North Korea conducted its third nuclear test. Immediately following the test, the Asian Institute for Policy Studies, a private think tank in South Korea, conducted a survey of 1,000 South Korean men and women aged 19 and over. According to the survey, 66.5 percent of the respondents agreed with the idea of South Korea arming itself with nuclear weapons to compete with North Korea. Kim Jiyoon, 43, the director of the survey, explained the result, saying, “The younger the respondents are, the more they’re opposed to holding nuclear weapons. Still, 50 percent of those less than 30 years old indicated support for the idea.” In another survey conducted in July 2014, a total of 52.7 percent of the respondents were in favor.

Is it possible that public opinion in South Korea could overturn the government’s non-nuclear stance? Han Yongsup, 59, a professor at the Korean National Defense University who previously was responsible for nuclear policy in the Ministry of National Defense, believes, “The alliance between South Korea and the United States is strong, so it isn’t likely that South Korea would dare leave the NPT and develop nuclear weapons. As the public is well aware of the fatigue in North Korea’s capacity as a nation, South Koreans won’t pursue such an extreme course.”

Instead, Mr. Han warns about the view of South Korean citizens toward Japan. He said, “In South Korea, there are suspicions over the large amount of plutonium held by Japan, which, in spite of its three non-nuclear principles, could be used to develop nuclear weapons.”

In June 2014, when the Japanese government reported on Japan’s stockpile of plutonium to the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), it failed to include 640 kilograms of plutonium, contained within spent fuel as a result of the accident at the Fukushima No. 1 (Daiichi) nuclear power plant. The media in Japan termed this an “omission,” but in South Korea, the media eyed this with suspicion, wondering whether Japan was in fact contemplating nuclear armament.

Jeon Jinho, 52, a professor at Kwangwoon University and an expert on the nuclear policies of Japan and South Korea, said, “In South Korea, which is competing with Japan over exports of nuclear power plant technology, there is increasing support for the idea of initiating the nuclear fuel cycle and stockpiling plutonium.” In fact, regulations on this point were partially eased in the revised nuclear agreement between South Korea and the United States, completed on April 22.

While under the U.S. nuclear umbrella, neither Japan nor South Korea have sought to hold their own nuclear arms. But with bilateral relations between these two nations at a low ebb, the denuclearization of Northeast Asia could become a more distant dream if they eye one other with rising suspicion over their nuclear policies.

--------------------

Issues involving civilian cooperation in Japan and South Korea

How can the citizens of Japan and South Korea work together to advance a world free of nuclear weapons? The Chugoku Shimbun interviewed Keisaburo Toyonaga, 79, the director of the Hiroshima branch of the “Association of Citizens for the Support of South Korean Atomic Bomb Victims,” and Kim Yeong Hwan, 42, the head of the external cooperation team of the Institute for Research in Collaborationist Activities, which specializes in studies of modern Korean history from the perspective of its relations with Japan.

Keisaburo Toyonaga, director of the Hiroshima branch of the Association of Citizens for the Support of South Korean Atomic Bomb Victims: Youth should engage in frank exchange

I have a connection with a youth group in the city of Daegu, South Korea. Five years ago, I lent support for their exhibition about the atomic bombings. When I went to see it, I was surprised because the exhibition was held along the corridor of a subway station. I told them that they should rent a hall somewhere so people could get a better look, but they said, “If we did, no one would come and see it. This is the only way to get the public to see the exhibition.”

This made me sharply aware of the large difference between the people of South Korea and the people of Japan when it comes to their interest in the A-bomb damage. On the other hand, these young people in South Korea showed real commitment in their diligent efforts to find a location that would give people the chance to learn more about the atomic bombings.

My activities in this area were prompted by an unexpected encounter. When I was a high school teacher in 1971, I was staying at a hotel the day before I went to South Korea for a training course. When I was watching TV at the hotel, I saw A-bomb survivors in South Korea on TV. I was shocked and I searched them out when I had time during my training.

I was appalled by the fact that these survivors weren’t eligible for relief from the Japanese government, so I became a member of a group of supporters and opened a branch here in Hiroshima. Since that time I have lent support to many lawsuits over this issue and I believe we were able to gain the understanding of many people for our campaign and move forward by positioning the problem as an issue of universal human rights: “A-bomb survivors are the same, no matter where they live.” I think the same goes for current discussions on the inhumanity of nuclear weapons, intended to advance nuclear disarmament worldwide.

The worsening relationship between Japan and South Korea concerns me, but I have hopes for the youth of both countries because young people can consider nuclear issues from the point of view of human rights. In South Korea, the older generation, with their vivid memory of Japan’s colonial rule, sees the atomic bombings as acts of liberation. The younger generation, though, doesn’t share this same perspective. If the young people of our two countries spoke frankly and shared their views on historical perceptions and other issues, I’m confident that such discussion would produce positive results.

Kim Yeong Hwan, head of the external cooperation team of the Institute for Research in Collaborationist Activities (in Seoul): Don’t be swayed by historical issues when dealing with nuclear disarmament

In South Korea, the issue of the A-bomb survivors is often viewed in the context of the unresolved postwar compensation from Japan, as well as the issue of the comfort women. There are far fewer opportunities for A-bomb survivors in South Korea to share their accounts, as messengers conveying the threat of nuclear weapons, compared to survivors in Japan.

Most South Koreans are predominantly concerned about the comfort women. I’m afraid they don’t show much interest in nuclear disarmament or nuclear abolition. They are also opposed to the idea of the Japanese thinking of themselves as victims, which gets emphasized when talk turns to the A-bomb damage.

However, I believe the number of people who view the bombings in a positive light, as an image of liberation from Japan’s colonial rule, has declined. Facing the threat of North Korea’s nuclear weapons, the people of South Korea have become more aware of the horrific damage caused by nuclear weapons. In South Korea, second-generation A-bomb survivors have launched a campaign for relief measures, which I support. There is now a foundation for antinuclear activities. If there can be collaboration with efforts in Japan, the movement will grow.

At the same time, I’m concerned that the problem of historical perceptions may be an obstacle to progress. The attitudes of the governments of Japan, headed by Shinzo Abe, and Korea, led by Park Geun-hye, may make things worse. The influence of these attitudes must be minimized and the citizens of both countries must work together to influence their governments.

When I was 25 years old, I took part in a joint Japan-South Korea project to unearth the remains of Korean nationals who were forced to labor in the construction of dams and railways in Hokkaido and died during the war. Since that time, based on the bond I developed with Japanese people in that project, I have continued my peace activities, traveling back and forth from South Korea to Japan. I believe we can make progress on the major goal of abolishing nuclear weapons, step by step, by promoting personal interaction and ties of friendship.

--------------------

Recommendation for denuclearization: A new road to peace in the region

Over the past nine years, North Korea has stubbornly pursued three nuclear tests. Russia revealed a reliance on its nuclear arsenal in connection with the crisis in Ukraine. China has been criticized for a lack of transparency regarding its nuclear weapons. Surrounded by these nations, Japan and South Korea have clung to the U.S. nuclear umbrella.

Seeing the current state of affairs in Northeast Asia, the road toward nuclear abolition looks bleak. The six-party talks to discuss North Korea’s nuclear issues remain at an impasse.

Seeking solutions, in April Nagasaki University’s Research Center for Nuclear Weapons Abolition (RECNA) announced its recommendation to establish a nuclear-weapon-free zone in Northeast Asia.

Appeal for proposal at NPT Review Conference

“If we only ask North Korea to denuclearize, nothing will happen. We should change our mindset to ease tensions in the region by negotiating a nuclear-weapon-free zone with the other nations that are involved,” stressed Tatsujiro Suzuki, 64, the new director of RECNA, who assumed his post from his predecessor, Hiromichi Umebayashi.

Mr. Suzuki continued, “I would like to strongly convey this recommendation as a proposal which originates from an A-bombed city.” RECNA will hold a gathering at this year’s Review Conference of the Nuclear Non-proliferation Treaty (NPT), opening on April 27, and appeal for the recommendation to the 190 NPT member nations. Mr. Suzuki is now busy making preparations for this effort with RECNA staff, including Keiko Nakamura, 42, an associate professor who will accompany him.

The recommendation is a “three-plus-three” proposal, which indicates the number of nations involved. The idea is that the first three countries--Japan, South Korea, and North Korea--will affirm that they won’t possess nuclear weapons while the other three countries--the United States, Russia, and China--will commit to not attacking or threatening the first three nations with nuclear weapons. The goal of the recommendation is to conclude a treaty. To realize this aim, the recommendation also urges a formal end to the Korean War, which even today remains under ceasefire conditions, and a “comprehensive framework agreement” for establishing ongoing conferences to discuss security issues.

Since the founding of RECNA at Nagasaki University three years ago, former senior government officials and security experts from these six nations, and RECNA staff, have held a series of discussions. The Hiroshima Peace Institute at Hiroshima City University has lent its support to this initiative and co-hosted RECNA’s international workshop. Efforts to flesh out and enact details of the recommendation will continue this year and beyond.

Whether this concept can be realized as actual policy depends on response of the Japanese government. After the recommendation was released, Mr. Suzuki and his staff visited the Ministry of Foreign Affairs on April 10 and requested that the government adopt this blueprint. Mr. Suzuki felt that some appreciation was given for the fact that the recommendation not only appeals for denuclearization, but also takes further steps by proposing “the path forward.” However, the Japanese government, which relies on U.S. nuclear deterrence, finds it difficult to pursue this path and attain the state where the nations of Northeast Asia no longer depend on nuclear arms to ensure security.

Underlying support from the public is crucial

“A nuclear-weapon-free zone could contribute to Japan’s security. Japan and South Korea should take the lead, with the Japanese leadership, in particular, seeking a breakthrough.” The Chugoku Shimbun spoke to Morton Halperin in Washington D.C. last December. Mr. Halperin is a former senior government official who had a range of key responsibilities for the United States. He strongly supports the idea of a nuclear-weapon-free zone in Northeast Asia. In fact, Mr. Halperin’s endorsement of RECNA’s recommendation lent momentum to the effort because he has extensive knowledge of U.S. nuclear strategy and the Japan-U.S. alliance.

Mr. Halperin said, “If Japan makes clear that it will never possess nuclear weapons and seeks the denuclearization of the region, South Korea will have no choice but to follow suit,” he said. “It would also eliminate skepticism over the question of South Korea assuming control over North Korea’s nuclear weapons when the Korean Peninsula is unified. China and Russia would welcome this as well.”

In 2010, the Obama administration announced that the United States would not use, or threaten to use, nuclear weapons against non-nuclear weapon states which abide by the NPT. Though current conditions don’t lend themselves to negotiations with North Korea, Mr. Halperin said with certainty, “The United States is also ready to accept the idea of a nuclear-weapon-free zone in Northeast Asia.”

How far will this proposal from an A-bombed city, based on existing nuclear-weapon-free zones in other regions of the world, be carried? Clearly, the underlying support from the broader public, with their hopes for nuclear abolition and regional peace, is crucial.

--------------------

Nuclear-weapon-free zones cover most of southern hemisphere, expanding north

In a nuclear-weapon-free zone, the countries of a given region pledge not to produce, obtain, or deploy nuclear weapons. Nuclear powers that are members of the NPT are obliged not to threaten or attack countries in a nuclear-weapon-free zone with their nuclear arms. Countries in these zones are required to conclude a treaty and comply with its principles.

The Antarctic Treaty, which took effect in 1961 and stipulates the peaceful use of Antarctica, is a precedent. The impetus for the first nuclear-weapon-free zone, established in Central and South America in 1968, was the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962, when the United States and the former Soviet Union came to the brink of nuclear war. Then, against the backdrop of regional issues, nuclear-weapon-free zones were established in other regions, such as the South Pacific Ocean area, which suffered serious damage as a consequence of nuclear tests conducted by the United States and other countries. In the northern hemisphere, Mongolia, enclosed by Russia and China, has sought to preserve its security by announcing its status as a single-state nuclear-weapon-free zone.

Meanwhile, some other regions have considered establishing a nuclear-weapon-free zone, but this goal has not yet materialized because one nation continues to pursue the development of nuclear arms despite opposition from its neighbors as well as adversarial relations between the countries concerned. Examples are the Middle East region, which includes Israel, a de facto nuclear weapon state outside the NPT framework, and the Northeast Asian region, which includes North Korea.

With regard to Northeast Asia, many versions of a nuclear-weapon-free zone have been proposed. In 2008, the Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ) prepared a draft treaty, an effort spearheaded by Katsuya Okada, the deputy leader of the DPJ at that time. However, a document titled “Japan’s Efforts on Disarmament and Non-Proliferation,” which was issued by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan in 2013, acknowledges that Japan isn’t prepared to advance a nuclear-weapon-free zone for the region, given the current state of China’s nuclear and conventional military forces.

Meanwhile, the nuclear-weapon-free areas of the world have expanded to include more than 100 countries, covering a large part of the southern hemisphere. In some cases, the feeling of momentum to establish a nuclear-weapon-free zone and the series of subsequent discussions among the countries concerned fostered mutual trust within the region and led to willingness to abandon nuclear arms. One example is South Africa, which had been secretly pursuing nuclear weapons development. And though Kazakhstan was once home to nuclear weapons on its territory, following the collapse of the Soviet Union, it completely denuclearized. Similarly, in South America, Brazil and Argentina have overcome divisions through dialogue that was prompted by interest in establishing a nuclear-weapon-free zone in the region.

The call for a nuclear weapons convention is now growing in the international community. But outlawing nuclear arms is difficult when nuclear-weapon-free zones have not yet spread worldwide. Moving both efforts forward is a means of achieving international security without relying on nuclear weapons, and eliminating them from the earth.

--------------------

Hiromichi Umebayashi, special advisor to Peace Depot: Beyond the nuclear umbrella

How feasible is the idea of establishing a nuclear-weapon-free zone in Northeast Asia? The Chugoku Shimbun spoke with Hiromichi Umebayashi, a special advisor to Peace Depot, a non-profit organization, and the former first director of the Research Center for Nuclear Weapons Abolition (RECNA) at Nagasaki University. He held this post until March 2015.

When you ended your term at RECNA, you compiled a recommendation for establishing a nuclear-weapon-free zone in Northeast Asia.

Northeast Asia suffers from complex issues involving territory and historical perception, and is very prone to the influence of U.S. policy. But I think it’s possible to independently pursue the theme of denuclearization in this region to important effect. Depending on circumstances, such efforts to advance denuclearization can promote discussion on other issues among countries in the region. I believe this is the challenge we should now pursue.

It seems most people don’t think it’s realistic that North Korea will abandon its nuclear ambitions.

This is the starting point of the discussion. North Korea has repeatedly stated its reason for seeking nuclear weapons. With the United States in mind, they say, “We’re facing a nuclear threat.” North Korea feels a sense of crisis, worried that their regime may be upended by the United States, as in Libya and Iraq.

If they no longer feel threatened by nuclear weapons or military might, there would be no reason for North Korea to maintain a nuclear arsenal. The intent of a nuclear-weapon-free zone is to eliminate nuclear threats from this region in a legally binding manner.

There is growing concern over China’s efforts to strengthen its nuclear capability.

Nuclear weapons in China represent its war-making capability on a global scale. Strengthening its arsenal is intended as a nuclear deterrent, to bolster its ability to retaliate against the United States. To halt this trend, the issue must be addressed along with the nuclear weapons held by the United States and Russia under a worldwide framework of denuclearization, centering on the NPT. There’s no reason, really, for China to strengthen its nuclear capability against the other nations of Northeast Asia, including Japan. I don’t think China’s actions are helpful, but they don’t necessarily make denuclearization more difficult in Northeast Asia.

What actions should Japan pursue?

At the beginning of the action plan that was agreed to at the NPT Review Conference in 2010, it states: “All States parties commit to pursue policies that are fully compatible with the Treaty and the objective of achieving a world without nuclear weapons.” As a country that relies on the U.S. nuclear umbrella, Japan, as well as South Korea, is being tested on its ability to move toward abandoning the nuclear umbrella for its security.

At this year’s Review Conference, we will call for establishing a nuclear-weapon-free zone in Northeast Asia. Subsequently, the six-party talks should be resumed to discuss this theme. We believe these are the actions Japan and South Korea should pursue. Though these two nations have a difficult relationship, they can advance common interests through dialogue.

If movement can be made, this would be a fruitful outcome.

There is skepticism over whether this Review Conference can bring about any meaningful results. With the United States and Russia now at loggerheads, the nuclear weapon states are not likely to propose bold measures. This is why I insist that Japan act to save the NPT. If a nation which relies on nuclear deterrence proposes a new idea, this could have a significant impact.

Profile

Hiromichi Umebayashi

Born in Hyogo Prefecture in 1937, he completed his Ph.D at the graduate school of the University of Tokyo. After working as a university lecturer, he founded Peace Depot, a private nuclear and peace research institute in Yokohama in 1998. He served as the director of RECNA from April 2012 to March 2015.

Major events involving nuclear weapons in Northeast Asia

August 1945

World War II ends.

August 1948

South Korea is established. North Korea is established in September.

August 1949

The Soviet Union conducts its first nuclear test.

June 1950

The Korean War begins. (Ceasefire agreement is reached in July 1953.)

January 1958

The U.S. military begins to deploy tactical nuclear weapons in South Korea.

October 1964

China conducts its first nuclear test.

June 1965

The Treaty on Basic Relations between Japan and South Korea is signed.

January 1968

Prime Minister Eisaku Sato announces the three non-nuclear principles as well as Japan’s reliance on U.S. nuclear deterrence.

March 1970

The Nuclear Non-proliferation Treaty (NPT) takes effect.

November 1971

Japan’s Lower House passes a resolution for the three non-nuclear principles to become national policy.

December 1985

North Korea joins the NPT.

December 1989

U.S. and the Soviet Union declare the end of the Cold War.

September 1991

U.S. President George H.W. Bush announces the removal of nuclear weapons deployed in South Korea.

December 1991

South Korea and North Korea agree to a joint declaration to denuclearize (takes effect in February 1992).

October 1992

Mongolia declares status as a “a one-state nuclear-weapon-free zone.” (U.N. approves it in December 1998.)

March 1993

North Korea announces its withdrawal from NPT regime in reaction to inspection of its nuclear facility. It retracts the announcement in June this same year.

October 1994

U.S. and North Korea sign a framework to freeze North Korea’s nuclear weapons program.

August 1998

North Korea conducts a test launch of the ballistic missile “Taep’o-dong.”

June 2000

First Inter-Korean Summit takes place.

October 2002

North Korea admits having a uranium enrichment plan to U.S.

January 2003

North Korea again announces its withdrawal from NPT. It also renounces the Inspection Convention with IAEA (International Atomic Energy Agency).

August 2003

The six-party talks begin.

February 2005

North Korea formally declares its possession of nuclear weapons.

September 2005

The six-party talks release the first joint statement incorporating denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula.

October 2006

North Korea conducts a nuclear test. The U.N. Security Council adopts a sanction resolution against North Korea.

December 2008

Chief delegates of the six-party talks meet. The meeting collapses over the issue of verifying North Korea’s nuclear activities.

April 2009

North Korea launches a long-range ballistic missile, calling it an “artificial satellite.”

May 2009

North Korea conducts its second nuclear test.

November 2010

North Korea shells Yeonpyeong island in South Korea.

February 2012

U.S. and North Korea agree on return of IAEA inspector and provision of food aid.

February 2013

North Korea conducts its third nuclear test.

April 2013

North Korea’s Standing Committee of the Supreme People’s Assembly adopts “Law on Consolidating the Position of a Nuclear Weapons State.”

September 2013

Mongolian president announces at the U.N. that Mongolia will contribute to establishing a nuclear-weapon-free zone in Northeast Asia.

Keywords

Six-party talks

Six-party talks are the multilateral discussions aimed at denuclearizing the Korean Peninsula. The first meeting was held in August 2003. Taking part are China, which serves as chair, Japan, the U.S., South Korea, Russia, and North Korea. A joint statement specifying that North Korea end its nuclear weapons program was adopted in September 2005. However, at the meeting in December 2008, North Korea objected to the method used to verify its denuclearization, and the talks were suspended. In January 2013, North Korea announced that the joint statement has become “extinct.”

(Originally published on April 25, 2015)