Hiroshima Asks: Toward the 70th Anniversary of the Atomic Bombing: The Marshall Islands pursues lawsuits to appeal for nuclear disarmament

Apr. 2, 2015

by Jumpei Fujimura, Staff Writer

In April 2014, the Marshall Islands filed lawsuits at the International Court of Justice in The Hague, the Netherlands. This small island nation, where the United States carried out 67 nuclear tests, argues that the nuclear weapon states are violating international law with respect to their nuclear disarmament obligations. Their claim is also an appeal for ridding the earth of nuclear weapons, and an effort to make the world more aware of the problems of the lasting damage to human health from radiation and necessary compensation for this damage.

Nuclear tests conducted by the United States have left deep scars on the islands and their residents. The residents of the coral atolls called the “Pearl Necklace of the Pacific” still endure suffering more than half a century after the last nuclear test was performed there in 1958.

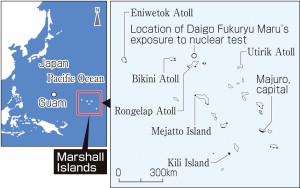

“I thought the sun had risen in the sky in the west, and wondered what was happening. Then I heard an explosion and saw palm trees shake,” said Lemeyo Abon, 74. She is from Rongelap Atoll, but now lives in Majuro, the capital. She clearly remembers the hydrogen bomb test on March 1, 1954, in which crew members of the Daigo Fukuryu Maru (The Lucky Dragon No. 5), a Japanese tuna fishing boat, were also exposed to radiation.

One of the largest nuclear blasts among the 67 nuclear tests shattered coral reefs at Bikini Atoll and blew their fragments into the atmosphere. The radioactive fallout, or “ashes of death,” reached Rongelap Atoll, located 170 kilometers to the east, contaminating the residents’ ancestral land and damaging the health of 86 people, including four fetuses.

According to reports from health surveys carried out by American doctors, 14 out of 19 residents who were 10 or younger at the time of the nuclear test had developed thyroid disorders by 1967, 13 years after the test. The number of miscarriages and stillbirths also rose sharply.

Ms. Abon was 13 at the time of the test. Her thyroid was removed because of cancer and she suffered two miscarriages. “Nuclear weapons have made a mess of my life. I can’t trust the U.S.,” she said. She does not want to go back to Rongelap, even though part of it has been decontaminated. She still recalls the bitter experience of returning there, three years after the nuclear test, when the United States declared the atoll fit to inhabit, but people came down with health problems and had to leave their homeland again.

Ms. Abon is frustrated that she is unable to hand down the abundant natural resources and traditional culture of her island to her children and grandchildren. With a stern expression, she said, “Must we pass on this negative legacy to future generations? We have to get rid of nuclear weapons.”

The 167 inhabitants of Bikini Atoll, where the nuclear tests were performed, were forced to move from their homeland. They and their offspring, now numbering 700, live on the island of Kili, located 760 kilometers southeast of Bikini. While visiting Majuro for a meeting with officials from the U.S. Department of Energy, Ichiro Mark, 72, said, “It’s hard to live on an isolated island where we can’t get enough food. One time, food wasn’t delivered because of rough weather and we almost starved.”

Kili, which was a deserted island, does not have a calm inland sea like many other atolls of the Marshall Islands. The island is not endowed with food like coconut crabs, and residents must rely on canned food provided by the United States as compensation. When the weather is stormy, high waves prevent the supply ship from approaching the island. The tradition of fishing from a canoe has been lost.

The United States carried out decontamination work in Bikini after the nuclear tests and declared it safe in 1968, as they did with Rongelap. Residents returned to Bikini and built schools and churches, but plutonium was found in their urine samples. The United States retracted its declaration in 1978, and access to Bikini was again sealed off.

“I want to go back to my homeland. If I can’t do that, at least let us move to a place where we can get enough food,” said Mr. Mark, his eyes wet with tears. He still cherishes his childhood memories of living amid the bounty of nature. His words convey how he is nearly at the point of abandoning his desire to return home and how hard his life has been.

The Chugoku Shimbun interviewed Seiichiro Takemine, an associate professor at Meisei University in Hino, Tokyo, who has been pursuing surveys on the impact of nuclear tests in the Marshall Islands.

What is the significance of the lawsuits filed by the Marshall Islands at the International Court of Justice (ICJ) against the nuclear weapon states?

It is a battle waged by a small island nation in the Pacific to revive its pride and dignity. Though the nation relies on aid from the United States, a nuclear superpower, it is only natural that it has raised its voice both as a nation that has learned firsthand the impact of radiation on human health and as a member of the international community. There is a limit to what a small country can do alone, so it joined hands with international NGOs. It is an adroit diplomatic strategy.

The lawsuits were filed partly with the desire to forge a breakthrough in deadlocked negotiations with the United States on compensation for damage caused by the nuclear tests. If the Marshall Islands can strengthen its presence, more attention will be paid to the damage it has suffered. The New York Times carried an article featuring this issue at the end of last year. The speech by the representative from the Marshall Islands is expected to draw attention at the Review Conference for the Nuclear Non-proliferation Treaty (NPT), scheduled to open at the end of April.

The problem faced by the Marshall Islands does not attract the attention of people in Japan, though similar damage was inflicted here.

The first nuclear test in the Marshall Islands was carried out in July 1946, less than one year after the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. To the United States, these three places exist in the course of its nuclear development program, which could not have been successful without the Marshall Islands. In considering the meaning of the Hiroshima bombing, we must not overlook this island nation.

The people of the Marshall Islands empathize with the people of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Even though U.S. research has said that the land is now livable, they remain anxious, and they feel that the people of the A-bombed cities will understand their suffering. They want the relief measures that were established in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, such as the counseling system by caseworkers, to be implemented in the Marshall Islands, too. The knowledge and experiences that have accumulated in Japan must be used to support the people of that nation.

Some specialists see the lawsuits as a reckless attempt. What do you think?

It is narrow pragmatism to judge this problem in terms of winning or losing the lawsuits. There is a good possibility that the lawsuits will influence international politics. Hiroshima and Nagasaki must learn from the Marshall Islands’ power to take action. This island nation with a population of 53,000 has made an impact on the world with its nimble action.

The lawsuits were filed in April of last year, shortly after the 60th anniversary of the “Castle Bravo” hydrogen bomb test, in which crew members of the Daigo Fukuryu Maru (The Lucky Dragon No. 5) and other boats were exposed to radiation. The Marshall Islands decided to look squarely at its suffering from radiation damage and take its first step as a country that was exposed to radiation. Passing down memories means making use of history across time and space. Japan will mark the 70th anniversary of the atomic bombings this year. What it can do at the national and popular levels will be put to the test.

Profile

Seiichiro Takemine

Born in 1977 in Itami, Hyogo Prefecture, Mr. Takemine is a graduate of the Waseda University Graduate School of Asia-Pacific Studies. After working as a researcher at Mie University, he assumed his current position in 2013. Mr. Takemine is co-representative of the Global Hibakusha Project and has authored The Marshall Islands: Owarinaki Kakuhigaio Ikiru (Living Through Endless Radiation Damage). He specializes in peace studies and global sociology.

As president of the Marshall Islands, I visited Hiroshima for the first time in February 2014. Touring Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum and listening to an A-bomb survivor made strong impressions on me. The experiences of Hiroshima and Nagasaki should have been a sufficient deterrent so that no other places in the world had to suffer a similar fate. The fact that nuclear tests were carried out in the Marshall Islands after the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki is highly regrettable.

As a lawyer in the 1970s, I often visited Rogenlap Atoll and other nuclear test sites that suffered damage. I had some knowledge about radiation injuries and the influence of radioactive fallout, but the visit to Hiroshima deepened my understanding of nuclear weapons and their damage and impact.

In the Marshall Islands, you can hear the experiences of people who had symptoms of acute radiation sickness and those who had more than one miscarriage after being exposed to radioactive fallout, but we don’t have a museum. I think we should have a facility like the peace museum in Hiroshima. The materials provided by the United States are limited to information about people who were exposed to highly radioactive fallout. But I believe all the land of the Marshall Islands has been damaged.

I will employ all possible measures and continue to call on the United States to enact justice and make reparations. The problem of radiation, a negative legacy, must be resolved. The government of the Marshall Islands asked the United Nations Human Rights Council to investigate this matter. And in 2012, the Council released a special report urging the United States to provide additional compensation. I will enlist support from the members of the Pacific Islands Forum (an inter-governmental organization to enhance cooperation between the countries in Oceania) and continue to negotiate with the United States, and get compensation.

Major incidents related to the Marshall Islands and nuclear weapons

October 1914: The Japanese Imperial Army occupies the Marshall Islands, then a German territory, putting it under practical control of Japan.

February 1944: U.S. military forces seize control of the Marshall Islands.

August 1945: Atomic bombs are dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

March 1946: The 167 residents of Bikini Atoll are forced to leave their islands before nuclear tests in the atoll.

July 1946: The U.S. conducts first atomic bomb test at Bikini Atoll.

July 1947: The United Nations approves the Marshall Islands becoming an American trusteeship. The U.S. Atomic Energy Commission announces it will make permanent nuclear test sites in the Marshall Islands.

April 1948: The U.S. begins conducting nuclear tests at Enewetak Atoll.

November 1952: The U.S. carries out the first hydrogen bomb test in history at Enewetak Atoll.

March 1954: The “Castle Bravo” hydrogen bomb test at Bikini Atoll is conducted. Crew members of the Daigo Fukuryu Maru (The Lucky Dragon No. 5) are exposed to a large amount of radioactive fallout from the bomb. The residents of Rongelap Atoll, located downwind, were evacuated off the island by the U.S.

June 1957: The U.S. declares Rongelap Atoll safe, and former residents return to the atoll.

July 1958: The last U.S. nuclear test in the Marshall Islands is carried out.

June 1983: The government of the Marshall Islands concludes a Compact of Free Association with the U.S., which includes compensation for the damage caused by nuclear testing.

May 1985: Because of health problems caused by residual radiation, 325 residents of Rangelop Atoll move to the uninhabited island of Mejatto.

October 1986: The Marshall Islands becomes an independent state in free association with the U.S.

April 2003: The Marshall Islands concludes a new Compact of Free Association with the U.S., which does not include a provision for additional compensation for victims of nuclear tests.

July 2010: Bikini Atoll is added to the World Cultural Heritage Site list.

September 2012: The U.N. Human Rights Council releases a special report urging the U.S. to provide additional compensation.

April 2014: The Marshall Islands files lawsuits against nine nuclear weapon states at the International Court of Justice.

Lawsuits signal responsibility of nation that suffered radiation damage

Majuro, the capital of the Marshall Islands, is 4,500 kilometers southeast of Japan. On the balcony of his home, overlooking the calm inland sea surrounded by coral reefs, Tony de Brum, the foreign minister of the Marshall Islands, said, “When you know how horrible radiation is, taking this action is only natural. With little progress being made in nuclear disarmament, there’s nothing to lose in raising our voices.” As a political leader, Mr. de Brum conveys the same message made by Peter Anjain, a resident of the islands, at a recent gathering held in Yaizu, Shizuoka Prefecture.

The news that an island nation with a population of 53,000 submitted its case to the International Court of Justice (ICJ), suing nine nuclear weapons states, surprised the world. Moreover, the nation has a Compact of Free Association with the United States, and 60 percent of its national budget comes from U.S. economic assistance.

Mr. de Brum, who played a leading role in the government’s effort to file the lawsuits, said that his nation, as a victim of radiation damage, has a responsibility to fulfill. He suggests that the United States has not been living up to its duty to strive for nuclear disarmament as stipulated in the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT). “As a long-time friend, I just advised them to make more serious efforts,” he said.

The lawsuits were pursued with the support of the Nuclear Age Peace Foundation, an American NGO, and the International Association of Lawyers against Nuclear Arms. The U.S. Conference of Mayors expressed its support and the International Peace Bureau awarded a prize, praising the nation’s courageous act. In this way, the lawsuits have engaged civil society.

Seeking no additional compensation

In the country itself, however, public reaction to the lawsuits is mixed because they specify that compensation for radiation damage will not be sought.

In 1983, when the Marshall Islands was seeking independence from its status as a trust territory, it concluded a Compact of Free Association with the United States. In this, the United States acknowledged that the four atolls of Bikini, Enewetak, Rongelap, and Utrōk suffered damage from nuclear tests and paid 150 million dollars in compensation.

With the conclusion of the compact, the problems of nuclear damage were determined to have been “completely resolved.” Later, an official document was found that other areas could have been affected by radioactive fallout. Also, the United Nations Human Rights Council urged the United States to provide additional compensation. No further reparations have been made, however, and a foundation that was established to manage the initial sum of compensation money ran out of funds in 2009. Residents of the islands have not been able to receive medical care benefits.

In these circumstances, the lawsuits have not been accepted positively by the whole nation. Kenneth Kedi, 43, a senator elected from Rongelap Atoll, is concerned that the lawsuits may send the wrong message, suggesting that the United States need not pay additional compensation. Radioactive debris has been removed from part of the islands, but even after 61 years, residents have not returned for fear of radiation. Mr. Kedi says that more extensive decontamination is necessary.

U.S. financial support is needed

Hiroshi Yamamura, 51, a senator elected from Utrōk Atoll, is a third-generation Japanese immigrant. He said in direct terms that making the United States angry will do more harm than good and that U.S. financial support is needed. More than 300 people still live on the island, which has yet to be decontaminated.

But neither senator has a clear idea about how to obtain additional compensation from the United States. Mr. Kedi said to me, “In a sense, the lawsuits are meaningful in that media from abroad have shown interest.”

The Marshall Islands, which knows the horror of radiation and the endless damage it wreaks, has been roiled by its responsibility. Signatories of the NPT can join the lawsuits as “parties concerned.” Mr. de Brum considers Japan “a brother in the nuclear age.”

He explained, “Just as the Marshall Islands is supported by U.S. economic aid, Japan is protected by the U.S. nuclear umbrella. But we share the desire not to see the tragedies caused by nuclear weapons occur again. We should be united by this strong bond, and work together for this cause.”

Process of lawsuits, and future prospects

The documents for the lawsuits filed by the Marshall Islands at the International Court of Justice (ICJ) are still being assembled.

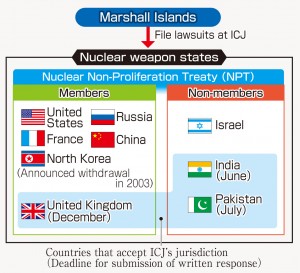

The Marshall Islands has sued the United States, Russia, the United Kingdom, France, and China, which are signatories to the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT); India, Pakistan, and Israel, which possess nuclear weapons but are non-members to the NPT; and North Korea, which has repeatedly conducted nuclear tests. The complaints argue that non-members of the NPT are also bound by nuclear disarmament obligations under customary international law.

It is expected that the case will mainly involve the United Kingdom, India, and Pakistan, because these countries have accepted the compulsory jurisdiction of the ICJ, which obligates these countries to be subject to the court’s jurisdiction. It is likely that the other six nations will not respond to the legal action, and will disregard its claims.

Despite accepting the ICJ’s jurisdiction, the United Kingdom, India, and Pakistan will each make a different response to the suits. India and Pakistan view matters relating to national sovereignty as not falling within their scope of consent to the court, arguing that their possession of nuclear arms is irrelevant. The ICJ has requested that India and Pakistan file a written response by June and July, respectively. But it is uncertain whether they will respond. The United Kingdom has not argued against compulsory jurisdiction and is expected to file its response by a December deadline.

In the judicial contest with the United Kingdom, nuclear disarmament obligations will be one of the points of dispute. Under the provisions of the ICJ, member countries of the NPT are entitled to join the legal effort as parties concerned. If they wish to do so, they are asked to make applications before the oral proceedings begin, which will be next year or later. Attention will be paid to the responses of Japan, which suffered the atomic bombings, and other nations that have put substantial efforts into nuclear disarmament and have been leading forces in the joint statements on the humanitarian consequences of nuclear weapons.

The Marshall Islands also filed a federal lawsuit against the United States at a district court in California last April. But the case was dismissed in February, with the court arguing that it is in no position to order the government to pursue nuclear disarmament.

Japan’s reaction: Government distances itself from lawsuits

Japan’s response to the lawsuits by the Marshall Islands at the ICJ has been lukewarm. Member countries of the NPT, including Japan, are entitled to join the legal effort as parties concerned. Some NGOs in Japan have expressed their support for the legal action. But the government has been aloof, saying that it will continue to carefully observe the situation. This attitude calls into question whether the Japanese government is serious, as it professes, about “leading the nuclear disarmament efforts as the only nation to have experienced nuclear attack.”

Foreign Minister Fumio Kishida has not offered his view on the lawsuits filed by the Marshall Islands, saying only that “The documentation procedure has just begun.” This was at a press conference on February 27, two days before the anniversary of Bikini Day on March 1, when fishing boats that included the Daigo Fukuryu Maru (The Lucky Dragon No. 5) were exposed to radioactive fallout from a U.S. hydrogen bomb test.

The government advocates a “realistic and practical approach” toward nuclear disarmament. This means that Japan will support only those measures which gain broad understanding from both non-nuclear and nuclear weapons states, including the United States, which shields Japan with its nuclear umbrella.

But Mr. Kishida did not go so far as to clearly criticize the legal action itself. “This should be interpreted based on future developments,” he said, the ambiguity of such answers reflecting his concern about the trend of public opinion at home and abroad.

The Japanese government seeks to avoid a replay of the bitter experience it encountered in 2013. In April of that year, it did not endorse a joint statement on the humanitarian consequences of nuclear weapons, which was signed by 80 nations. This stance was harshly criticized by people in Hiroshima and Nagasaki as well as in other parts of the country and in the world. Six months later, the government made an about-face and lent its support to a similar statement. As a result, the government is waiting to see how much support the international community will give to the lawsuits filed by the Marshall Islands.

On the other hand, some NGOs in Japan have expressed support for the lawsuits. Last July, the Japan Association of Lawyers Against Nuclear Arms made a statement which backs the lawsuits by the Marshall Islands and sent a message to the country’s embassy in Tokyo. Soka Gakkai collected 5.12 million signatures which support the lawsuits and handed them to Foreign Minister Tony de Brum during the Conference on the Humanitarian Impact of Nuclear Weapons held in Vienna, Austria in December 2014.

Kenichi Okubo, secretary general of the Japan Association of Lawyers Against Nuclear Arms, said, “This is a good opportunity to increase public awareness and encourage the Japanese government to join the lawsuits.”

Damage to crews on Japanese boats unclear

On March 1, 1954, a hydrogen bomb test was conducted by the United States at Bikini Atoll. In Japan, it is widely known that crew members of the Daigo Fukuryu Maru (The Lucky Dragon No. 5), a Japanese tuna fishing boat from Yaizu, Shizuoka Prefecture, were exposed to radioactive fallout from the bomb. But around 1,000 Japanese boats are believed to have been in the same waters of the Pacific Ocean, and the full scope of the damage done to these vessels and their crews is not clear.

The Kochi Prefecture Pacific Ocean Nuclear Test Suffering Support Center, located in Sukumo, Kochi Prefecture, has been pursuing follow-up investigations. Upon the group’s request, the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare disclosed 1,900 pages of related documents last September. These documents explain the circumstances surrounding 556 boats when they were exposed to radiation. The government contends that the exposure doses in these cases were much lower than the international standards with regard to the increased risk of cancer and other diseases. However, some specialists claim that internal exposure and other factors have not been taken into consideration.

This past January, the Health Ministry assembled a group to study how former crew members of the boats other than the Daigo Fukuryu Maru were exposed to radiation from the nuclear test. The group has begun working on an estimate of the exposure doses based on the disclosed documents and other materials written around the time of the test.

Keywords

Nuclear tests conducted in the Marshall Islands

The United States carried out 67 atomic and hydrogen bomb tests from 1946 through 1958 at the two atolls of Bikini and Enewetak in the Marshall Islands, located in the Central Pacific Ocean. These tests were conducted against the backdrop of the nuclear arms race between the U.S. and the former Soviet Union. The destructive force of these bomb tests totaled 108 megatons of TNT, equivalent to 7,000 Hiroshima atomic bombs. In particular, the “Castle Bravo” hydrogen bomb test at Bikini Atoll on March 1, 1954 released a large amount of nuclear fallout into the atmosphere. The explosive power of the bomb was 15 megatons, which is 1,000 times as powerful as the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima. Residents of nearby islands were exposed to radiation since no evacuation warning was issued in advance. Japanese tuna fishing boats, including crew members of the Daigo Fukuryu Maru (The Lucky Dragon No. 5), were also exposed to radioactive fallout. Aikichi Kuboyama, the chief radio operator of the Daigo Fukuryu Maru, died six months later. This incident triggered the ban-the-bomb movement.

The International Court of Justice (ICJ) and controversy surrounding nuclear weapons

The ICJ, located in The Hague, the Netherlands, is authorized to solve international legal disputes between nations or to state advisory opinions on legal questions referred to it by international organs. The ICJ examined the legality of the use of nuclear weapons in response to a request from the United Nations following a resolution adopted in 1994. In 1995, then Hiroshima Mayor Takashi Hiraoka argued that nuclear weapons are against international law, but the Japanese government did not claim such weapons were illegal. In its advisory opinion issued in 1996, the ICJ ruled that "the threat or use of nuclear weapons would generally be contrary to the rules of international law." But at the same time, the opinion stated, "The Court cannot conclude definitively whether the threat or use of nuclear weapons would be lawful or unlawful in an extreme circumstance of self-defense, in which the very survival of a state would be at stake."

Compact of Free Association and compensation for nuclear damage

The Marshall Islands concluded a Compact of Free Association with the United States in 1983. In line with this agreement, it became an independent state from a U.N. trust territory in 1986. The Marshall Islands gave part of its military and security rights to the U.S. and received 150 million dollars of economic assistance in compensation for the damage caused by nuclear testing. When the compact was renewed in 2003, the Marshall Islands asked the United States to provide additional compensation. But this request was turned down, with the U.S. arguing that all pertinent problems had been solved. Separately, the Rongelap Atoll Local Government negotiated directly with the U.S. and obtained 45 million dollars for resettlement and other expenses in 1996.

The Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT)

The NPT is the only treaty on nuclear disarmament. It has a total membership of 190 nations. The treaty permits the possession of nuclear weapons by the United States, Russia, the United Kingdom, France, and China, while imposing on them the obligation to pursue negotiations for nuclear disarmament. The treaty grants non-nuclear-weapon states the right to the peaceful use of nuclear energy. The treaty took effect in 1970 and was extended indefinitely in 1995. Japan ratified the treaty in 1976. India, Pakistan, and Israel, which are de facto nuclear weapon states, have not joined the treaty. North Korea withdrew from the NPT in 2003. An NPT Review Conference is held every five years to assess the implementation of the treaty. The next Review Conference will open on April 27 at United Nations headquarters in New York.

(Originally published on March 14, 2015)

In April 2014, the Marshall Islands filed lawsuits at the International Court of Justice in The Hague, the Netherlands. This small island nation, where the United States carried out 67 nuclear tests, argues that the nuclear weapon states are violating international law with respect to their nuclear disarmament obligations. Their claim is also an appeal for ridding the earth of nuclear weapons, and an effort to make the world more aware of the problems of the lasting damage to human health from radiation and necessary compensation for this damage.

Suffering persists more than half a century after nuclear tests

Nuclear tests conducted by the United States have left deep scars on the islands and their residents. The residents of the coral atolls called the “Pearl Necklace of the Pacific” still endure suffering more than half a century after the last nuclear test was performed there in 1958.

“I thought the sun had risen in the sky in the west, and wondered what was happening. Then I heard an explosion and saw palm trees shake,” said Lemeyo Abon, 74. She is from Rongelap Atoll, but now lives in Majuro, the capital. She clearly remembers the hydrogen bomb test on March 1, 1954, in which crew members of the Daigo Fukuryu Maru (The Lucky Dragon No. 5), a Japanese tuna fishing boat, were also exposed to radiation.

Traditional culture has been lost

One of the largest nuclear blasts among the 67 nuclear tests shattered coral reefs at Bikini Atoll and blew their fragments into the atmosphere. The radioactive fallout, or “ashes of death,” reached Rongelap Atoll, located 170 kilometers to the east, contaminating the residents’ ancestral land and damaging the health of 86 people, including four fetuses.

According to reports from health surveys carried out by American doctors, 14 out of 19 residents who were 10 or younger at the time of the nuclear test had developed thyroid disorders by 1967, 13 years after the test. The number of miscarriages and stillbirths also rose sharply.

Ms. Abon was 13 at the time of the test. Her thyroid was removed because of cancer and she suffered two miscarriages. “Nuclear weapons have made a mess of my life. I can’t trust the U.S.,” she said. She does not want to go back to Rongelap, even though part of it has been decontaminated. She still recalls the bitter experience of returning there, three years after the nuclear test, when the United States declared the atoll fit to inhabit, but people came down with health problems and had to leave their homeland again.

Ms. Abon is frustrated that she is unable to hand down the abundant natural resources and traditional culture of her island to her children and grandchildren. With a stern expression, she said, “Must we pass on this negative legacy to future generations? We have to get rid of nuclear weapons.”

Forced from their homeland

The 167 inhabitants of Bikini Atoll, where the nuclear tests were performed, were forced to move from their homeland. They and their offspring, now numbering 700, live on the island of Kili, located 760 kilometers southeast of Bikini. While visiting Majuro for a meeting with officials from the U.S. Department of Energy, Ichiro Mark, 72, said, “It’s hard to live on an isolated island where we can’t get enough food. One time, food wasn’t delivered because of rough weather and we almost starved.”

Kili, which was a deserted island, does not have a calm inland sea like many other atolls of the Marshall Islands. The island is not endowed with food like coconut crabs, and residents must rely on canned food provided by the United States as compensation. When the weather is stormy, high waves prevent the supply ship from approaching the island. The tradition of fishing from a canoe has been lost.

The United States carried out decontamination work in Bikini after the nuclear tests and declared it safe in 1968, as they did with Rongelap. Residents returned to Bikini and built schools and churches, but plutonium was found in their urine samples. The United States retracted its declaration in 1978, and access to Bikini was again sealed off.

“I want to go back to my homeland. If I can’t do that, at least let us move to a place where we can get enough food,” said Mr. Mark, his eyes wet with tears. He still cherishes his childhood memories of living amid the bounty of nature. His words convey how he is nearly at the point of abandoning his desire to return home and how hard his life has been.

Interview with Seiichiro Takemine, associate professor at Meisei University: Lawsuits by Marshall Islands may influence international politics

How should Japan respond to the lawsuits filed by the Marshall Islands?

The Chugoku Shimbun interviewed Seiichiro Takemine, an associate professor at Meisei University in Hino, Tokyo, who has been pursuing surveys on the impact of nuclear tests in the Marshall Islands.

What is the significance of the lawsuits filed by the Marshall Islands at the International Court of Justice (ICJ) against the nuclear weapon states?

It is a battle waged by a small island nation in the Pacific to revive its pride and dignity. Though the nation relies on aid from the United States, a nuclear superpower, it is only natural that it has raised its voice both as a nation that has learned firsthand the impact of radiation on human health and as a member of the international community. There is a limit to what a small country can do alone, so it joined hands with international NGOs. It is an adroit diplomatic strategy.

The lawsuits were filed partly with the desire to forge a breakthrough in deadlocked negotiations with the United States on compensation for damage caused by the nuclear tests. If the Marshall Islands can strengthen its presence, more attention will be paid to the damage it has suffered. The New York Times carried an article featuring this issue at the end of last year. The speech by the representative from the Marshall Islands is expected to draw attention at the Review Conference for the Nuclear Non-proliferation Treaty (NPT), scheduled to open at the end of April.

The problem faced by the Marshall Islands does not attract the attention of people in Japan, though similar damage was inflicted here.

The first nuclear test in the Marshall Islands was carried out in July 1946, less than one year after the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. To the United States, these three places exist in the course of its nuclear development program, which could not have been successful without the Marshall Islands. In considering the meaning of the Hiroshima bombing, we must not overlook this island nation.

The people of the Marshall Islands empathize with the people of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Even though U.S. research has said that the land is now livable, they remain anxious, and they feel that the people of the A-bombed cities will understand their suffering. They want the relief measures that were established in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, such as the counseling system by caseworkers, to be implemented in the Marshall Islands, too. The knowledge and experiences that have accumulated in Japan must be used to support the people of that nation.

Some specialists see the lawsuits as a reckless attempt. What do you think?

It is narrow pragmatism to judge this problem in terms of winning or losing the lawsuits. There is a good possibility that the lawsuits will influence international politics. Hiroshima and Nagasaki must learn from the Marshall Islands’ power to take action. This island nation with a population of 53,000 has made an impact on the world with its nimble action.

The lawsuits were filed in April of last year, shortly after the 60th anniversary of the “Castle Bravo” hydrogen bomb test, in which crew members of the Daigo Fukuryu Maru (The Lucky Dragon No. 5) and other boats were exposed to radiation. The Marshall Islands decided to look squarely at its suffering from radiation damage and take its first step as a country that was exposed to radiation. Passing down memories means making use of history across time and space. Japan will mark the 70th anniversary of the atomic bombings this year. What it can do at the national and popular levels will be put to the test.

Profile

Seiichiro Takemine

Born in 1977 in Itami, Hyogo Prefecture, Mr. Takemine is a graduate of the Waseda University Graduate School of Asia-Pacific Studies. After working as a researcher at Mie University, he assumed his current position in 2013. Mr. Takemine is co-representative of the Global Hibakusha Project and has authored The Marshall Islands: Owarinaki Kakuhigaio Ikiru (Living Through Endless Radiation Damage). He specializes in peace studies and global sociology.

Excerpt of interview with Christopher Loeak, president of the Marshall Islands: All-out effort to solve problem of negative legacy

As president of the Marshall Islands, I visited Hiroshima for the first time in February 2014. Touring Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum and listening to an A-bomb survivor made strong impressions on me. The experiences of Hiroshima and Nagasaki should have been a sufficient deterrent so that no other places in the world had to suffer a similar fate. The fact that nuclear tests were carried out in the Marshall Islands after the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki is highly regrettable.

As a lawyer in the 1970s, I often visited Rogenlap Atoll and other nuclear test sites that suffered damage. I had some knowledge about radiation injuries and the influence of radioactive fallout, but the visit to Hiroshima deepened my understanding of nuclear weapons and their damage and impact.

In the Marshall Islands, you can hear the experiences of people who had symptoms of acute radiation sickness and those who had more than one miscarriage after being exposed to radioactive fallout, but we don’t have a museum. I think we should have a facility like the peace museum in Hiroshima. The materials provided by the United States are limited to information about people who were exposed to highly radioactive fallout. But I believe all the land of the Marshall Islands has been damaged.

I will employ all possible measures and continue to call on the United States to enact justice and make reparations. The problem of radiation, a negative legacy, must be resolved. The government of the Marshall Islands asked the United Nations Human Rights Council to investigate this matter. And in 2012, the Council released a special report urging the United States to provide additional compensation. I will enlist support from the members of the Pacific Islands Forum (an inter-governmental organization to enhance cooperation between the countries in Oceania) and continue to negotiate with the United States, and get compensation.

Major incidents related to the Marshall Islands and nuclear weapons

October 1914: The Japanese Imperial Army occupies the Marshall Islands, then a German territory, putting it under practical control of Japan.

February 1944: U.S. military forces seize control of the Marshall Islands.

August 1945: Atomic bombs are dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

March 1946: The 167 residents of Bikini Atoll are forced to leave their islands before nuclear tests in the atoll.

July 1946: The U.S. conducts first atomic bomb test at Bikini Atoll.

July 1947: The United Nations approves the Marshall Islands becoming an American trusteeship. The U.S. Atomic Energy Commission announces it will make permanent nuclear test sites in the Marshall Islands.

April 1948: The U.S. begins conducting nuclear tests at Enewetak Atoll.

November 1952: The U.S. carries out the first hydrogen bomb test in history at Enewetak Atoll.

March 1954: The “Castle Bravo” hydrogen bomb test at Bikini Atoll is conducted. Crew members of the Daigo Fukuryu Maru (The Lucky Dragon No. 5) are exposed to a large amount of radioactive fallout from the bomb. The residents of Rongelap Atoll, located downwind, were evacuated off the island by the U.S.

June 1957: The U.S. declares Rongelap Atoll safe, and former residents return to the atoll.

July 1958: The last U.S. nuclear test in the Marshall Islands is carried out.

June 1983: The government of the Marshall Islands concludes a Compact of Free Association with the U.S., which includes compensation for the damage caused by nuclear testing.

May 1985: Because of health problems caused by residual radiation, 325 residents of Rangelop Atoll move to the uninhabited island of Mejatto.

October 1986: The Marshall Islands becomes an independent state in free association with the U.S.

April 2003: The Marshall Islands concludes a new Compact of Free Association with the U.S., which does not include a provision for additional compensation for victims of nuclear tests.

July 2010: Bikini Atoll is added to the World Cultural Heritage Site list.

September 2012: The U.N. Human Rights Council releases a special report urging the U.S. to provide additional compensation.

April 2014: The Marshall Islands files lawsuits against nine nuclear weapon states at the International Court of Justice.

Lawsuits signal responsibility of nation that suffered radiation damage

Majuro, the capital of the Marshall Islands, is 4,500 kilometers southeast of Japan. On the balcony of his home, overlooking the calm inland sea surrounded by coral reefs, Tony de Brum, the foreign minister of the Marshall Islands, said, “When you know how horrible radiation is, taking this action is only natural. With little progress being made in nuclear disarmament, there’s nothing to lose in raising our voices.” As a political leader, Mr. de Brum conveys the same message made by Peter Anjain, a resident of the islands, at a recent gathering held in Yaizu, Shizuoka Prefecture.

The news that an island nation with a population of 53,000 submitted its case to the International Court of Justice (ICJ), suing nine nuclear weapons states, surprised the world. Moreover, the nation has a Compact of Free Association with the United States, and 60 percent of its national budget comes from U.S. economic assistance.

Mr. de Brum, who played a leading role in the government’s effort to file the lawsuits, said that his nation, as a victim of radiation damage, has a responsibility to fulfill. He suggests that the United States has not been living up to its duty to strive for nuclear disarmament as stipulated in the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT). “As a long-time friend, I just advised them to make more serious efforts,” he said.

The lawsuits were pursued with the support of the Nuclear Age Peace Foundation, an American NGO, and the International Association of Lawyers against Nuclear Arms. The U.S. Conference of Mayors expressed its support and the International Peace Bureau awarded a prize, praising the nation’s courageous act. In this way, the lawsuits have engaged civil society.

Seeking no additional compensation

In the country itself, however, public reaction to the lawsuits is mixed because they specify that compensation for radiation damage will not be sought.

In 1983, when the Marshall Islands was seeking independence from its status as a trust territory, it concluded a Compact of Free Association with the United States. In this, the United States acknowledged that the four atolls of Bikini, Enewetak, Rongelap, and Utrōk suffered damage from nuclear tests and paid 150 million dollars in compensation.

With the conclusion of the compact, the problems of nuclear damage were determined to have been “completely resolved.” Later, an official document was found that other areas could have been affected by radioactive fallout. Also, the United Nations Human Rights Council urged the United States to provide additional compensation. No further reparations have been made, however, and a foundation that was established to manage the initial sum of compensation money ran out of funds in 2009. Residents of the islands have not been able to receive medical care benefits.

In these circumstances, the lawsuits have not been accepted positively by the whole nation. Kenneth Kedi, 43, a senator elected from Rongelap Atoll, is concerned that the lawsuits may send the wrong message, suggesting that the United States need not pay additional compensation. Radioactive debris has been removed from part of the islands, but even after 61 years, residents have not returned for fear of radiation. Mr. Kedi says that more extensive decontamination is necessary.

U.S. financial support is needed

Hiroshi Yamamura, 51, a senator elected from Utrōk Atoll, is a third-generation Japanese immigrant. He said in direct terms that making the United States angry will do more harm than good and that U.S. financial support is needed. More than 300 people still live on the island, which has yet to be decontaminated.

But neither senator has a clear idea about how to obtain additional compensation from the United States. Mr. Kedi said to me, “In a sense, the lawsuits are meaningful in that media from abroad have shown interest.”

The Marshall Islands, which knows the horror of radiation and the endless damage it wreaks, has been roiled by its responsibility. Signatories of the NPT can join the lawsuits as “parties concerned.” Mr. de Brum considers Japan “a brother in the nuclear age.”

He explained, “Just as the Marshall Islands is supported by U.S. economic aid, Japan is protected by the U.S. nuclear umbrella. But we share the desire not to see the tragedies caused by nuclear weapons occur again. We should be united by this strong bond, and work together for this cause.”

Process of lawsuits, and future prospects

The documents for the lawsuits filed by the Marshall Islands at the International Court of Justice (ICJ) are still being assembled.

The Marshall Islands has sued the United States, Russia, the United Kingdom, France, and China, which are signatories to the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT); India, Pakistan, and Israel, which possess nuclear weapons but are non-members to the NPT; and North Korea, which has repeatedly conducted nuclear tests. The complaints argue that non-members of the NPT are also bound by nuclear disarmament obligations under customary international law.

It is expected that the case will mainly involve the United Kingdom, India, and Pakistan, because these countries have accepted the compulsory jurisdiction of the ICJ, which obligates these countries to be subject to the court’s jurisdiction. It is likely that the other six nations will not respond to the legal action, and will disregard its claims.

Despite accepting the ICJ’s jurisdiction, the United Kingdom, India, and Pakistan will each make a different response to the suits. India and Pakistan view matters relating to national sovereignty as not falling within their scope of consent to the court, arguing that their possession of nuclear arms is irrelevant. The ICJ has requested that India and Pakistan file a written response by June and July, respectively. But it is uncertain whether they will respond. The United Kingdom has not argued against compulsory jurisdiction and is expected to file its response by a December deadline.

In the judicial contest with the United Kingdom, nuclear disarmament obligations will be one of the points of dispute. Under the provisions of the ICJ, member countries of the NPT are entitled to join the legal effort as parties concerned. If they wish to do so, they are asked to make applications before the oral proceedings begin, which will be next year or later. Attention will be paid to the responses of Japan, which suffered the atomic bombings, and other nations that have put substantial efforts into nuclear disarmament and have been leading forces in the joint statements on the humanitarian consequences of nuclear weapons.

The Marshall Islands also filed a federal lawsuit against the United States at a district court in California last April. But the case was dismissed in February, with the court arguing that it is in no position to order the government to pursue nuclear disarmament.

Japan’s reaction: Government distances itself from lawsuits

Japan’s response to the lawsuits by the Marshall Islands at the ICJ has been lukewarm. Member countries of the NPT, including Japan, are entitled to join the legal effort as parties concerned. Some NGOs in Japan have expressed their support for the legal action. But the government has been aloof, saying that it will continue to carefully observe the situation. This attitude calls into question whether the Japanese government is serious, as it professes, about “leading the nuclear disarmament efforts as the only nation to have experienced nuclear attack.”

Foreign Minister Fumio Kishida has not offered his view on the lawsuits filed by the Marshall Islands, saying only that “The documentation procedure has just begun.” This was at a press conference on February 27, two days before the anniversary of Bikini Day on March 1, when fishing boats that included the Daigo Fukuryu Maru (The Lucky Dragon No. 5) were exposed to radioactive fallout from a U.S. hydrogen bomb test.

The government advocates a “realistic and practical approach” toward nuclear disarmament. This means that Japan will support only those measures which gain broad understanding from both non-nuclear and nuclear weapons states, including the United States, which shields Japan with its nuclear umbrella.

But Mr. Kishida did not go so far as to clearly criticize the legal action itself. “This should be interpreted based on future developments,” he said, the ambiguity of such answers reflecting his concern about the trend of public opinion at home and abroad.

The Japanese government seeks to avoid a replay of the bitter experience it encountered in 2013. In April of that year, it did not endorse a joint statement on the humanitarian consequences of nuclear weapons, which was signed by 80 nations. This stance was harshly criticized by people in Hiroshima and Nagasaki as well as in other parts of the country and in the world. Six months later, the government made an about-face and lent its support to a similar statement. As a result, the government is waiting to see how much support the international community will give to the lawsuits filed by the Marshall Islands.

On the other hand, some NGOs in Japan have expressed support for the lawsuits. Last July, the Japan Association of Lawyers Against Nuclear Arms made a statement which backs the lawsuits by the Marshall Islands and sent a message to the country’s embassy in Tokyo. Soka Gakkai collected 5.12 million signatures which support the lawsuits and handed them to Foreign Minister Tony de Brum during the Conference on the Humanitarian Impact of Nuclear Weapons held in Vienna, Austria in December 2014.

Kenichi Okubo, secretary general of the Japan Association of Lawyers Against Nuclear Arms, said, “This is a good opportunity to increase public awareness and encourage the Japanese government to join the lawsuits.”

Damage to crews on Japanese boats unclear

On March 1, 1954, a hydrogen bomb test was conducted by the United States at Bikini Atoll. In Japan, it is widely known that crew members of the Daigo Fukuryu Maru (The Lucky Dragon No. 5), a Japanese tuna fishing boat from Yaizu, Shizuoka Prefecture, were exposed to radioactive fallout from the bomb. But around 1,000 Japanese boats are believed to have been in the same waters of the Pacific Ocean, and the full scope of the damage done to these vessels and their crews is not clear.

The Kochi Prefecture Pacific Ocean Nuclear Test Suffering Support Center, located in Sukumo, Kochi Prefecture, has been pursuing follow-up investigations. Upon the group’s request, the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare disclosed 1,900 pages of related documents last September. These documents explain the circumstances surrounding 556 boats when they were exposed to radiation. The government contends that the exposure doses in these cases were much lower than the international standards with regard to the increased risk of cancer and other diseases. However, some specialists claim that internal exposure and other factors have not been taken into consideration.

This past January, the Health Ministry assembled a group to study how former crew members of the boats other than the Daigo Fukuryu Maru were exposed to radiation from the nuclear test. The group has begun working on an estimate of the exposure doses based on the disclosed documents and other materials written around the time of the test.

Keywords

Nuclear tests conducted in the Marshall Islands

The United States carried out 67 atomic and hydrogen bomb tests from 1946 through 1958 at the two atolls of Bikini and Enewetak in the Marshall Islands, located in the Central Pacific Ocean. These tests were conducted against the backdrop of the nuclear arms race between the U.S. and the former Soviet Union. The destructive force of these bomb tests totaled 108 megatons of TNT, equivalent to 7,000 Hiroshima atomic bombs. In particular, the “Castle Bravo” hydrogen bomb test at Bikini Atoll on March 1, 1954 released a large amount of nuclear fallout into the atmosphere. The explosive power of the bomb was 15 megatons, which is 1,000 times as powerful as the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima. Residents of nearby islands were exposed to radiation since no evacuation warning was issued in advance. Japanese tuna fishing boats, including crew members of the Daigo Fukuryu Maru (The Lucky Dragon No. 5), were also exposed to radioactive fallout. Aikichi Kuboyama, the chief radio operator of the Daigo Fukuryu Maru, died six months later. This incident triggered the ban-the-bomb movement.

The International Court of Justice (ICJ) and controversy surrounding nuclear weapons

The ICJ, located in The Hague, the Netherlands, is authorized to solve international legal disputes between nations or to state advisory opinions on legal questions referred to it by international organs. The ICJ examined the legality of the use of nuclear weapons in response to a request from the United Nations following a resolution adopted in 1994. In 1995, then Hiroshima Mayor Takashi Hiraoka argued that nuclear weapons are against international law, but the Japanese government did not claim such weapons were illegal. In its advisory opinion issued in 1996, the ICJ ruled that "the threat or use of nuclear weapons would generally be contrary to the rules of international law." But at the same time, the opinion stated, "The Court cannot conclude definitively whether the threat or use of nuclear weapons would be lawful or unlawful in an extreme circumstance of self-defense, in which the very survival of a state would be at stake."

Compact of Free Association and compensation for nuclear damage

The Marshall Islands concluded a Compact of Free Association with the United States in 1983. In line with this agreement, it became an independent state from a U.N. trust territory in 1986. The Marshall Islands gave part of its military and security rights to the U.S. and received 150 million dollars of economic assistance in compensation for the damage caused by nuclear testing. When the compact was renewed in 2003, the Marshall Islands asked the United States to provide additional compensation. But this request was turned down, with the U.S. arguing that all pertinent problems had been solved. Separately, the Rongelap Atoll Local Government negotiated directly with the U.S. and obtained 45 million dollars for resettlement and other expenses in 1996.

The Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT)

The NPT is the only treaty on nuclear disarmament. It has a total membership of 190 nations. The treaty permits the possession of nuclear weapons by the United States, Russia, the United Kingdom, France, and China, while imposing on them the obligation to pursue negotiations for nuclear disarmament. The treaty grants non-nuclear-weapon states the right to the peaceful use of nuclear energy. The treaty took effect in 1970 and was extended indefinitely in 1995. Japan ratified the treaty in 1976. India, Pakistan, and Israel, which are de facto nuclear weapon states, have not joined the treaty. North Korea withdrew from the NPT in 2003. An NPT Review Conference is held every five years to assess the implementation of the treaty. The next Review Conference will open on April 27 at United Nations headquarters in New York.

(Originally published on March 14, 2015)