Hiroshima: 70 Years After the A-bombing: Mobilized Students 6

Jul. 14, 2015

Sister left home to help with the war effort, died that night

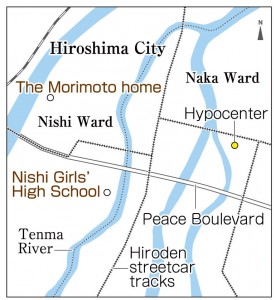

Nishi Girls’ High School was also a casualty of the atomic bombing. Located about 1.3 kilometers from the hypocenter, the school buildings faced the right bank of the Tenma River in Higashikanon-machi (now part of Nishi Ward) and were completely destroyed and burned to the ground. The school was founded back in 1927, but its history was interrupted.

“The area looks completely different”

Eiko Morimoto (née Iwai), 86, a resident of Nishi Ward, gazed around the place where her school once stood with a mixture of nostalgia and loneliness.

She said, “The area looks completely different. There probably aren’t many people who even know the school existed.” Homes have now sprouted in this location and no monument stands as a reminder of Nishi Girls’ High School. Now that they’re older, she said, her classmates no longer get together as they once did. Her school exists only in memory.

In the spring of 1941, Ms. Morimoto entered the school with her twin sister, Teiko. (Teiko died in 2007 at the age of 79.) There were about 100 students in each grade level. She recalled, “There was a friendly atmosphere in our school and I felt close to the teachers.” She eagerly learned kimono- and dress-making and formal manners. But the wartime mobilization of students then began after Japan also took on the United States and the United Kingdom and conditions deteriorated.

After becoming a fourth-year student, Ms. Morimoto worked for Showa Kinzoku Kogyo in Nishikanon-machi (now part of Nishi Ward). She helped produce tail units for aircraft and parts of fuel tanks.

Ms. Morimoto drilled holes in duralumin plates and drove in tacks with a hammer, wearing a headband with the word “Kamikaze” written on it. About 150 centimeters tall, she suffered from poor nutrition and did not have adequate time to rest. Nevertheless, the mobilized students worked hard, sacrificing themselves for the good of the nation, and more than a few developed health problems.

After attending a simple graduation ceremony in the spring of 1945, she entered the advanced course and was mobilized for the war effort. Kiwako, then 12, her younger sister and the third daughter of the Morimoto family, entered Nishi Girls’ High School at that time.

On August 6, Ms. Morimoto experienced the atomic bombing while at a rice shop near her home in Fukushima-cho (now part of Nishi Ward). The factory where she had been mobilized to work was closed because of a shortage of materials. Kiwako was mobilized to help tear down homes to create a fire lane in Koami-cho (now part of Naka Ward) and was set to depart for her work assignment.

Her mother, Fumi, tried to stop Kiwako from going, but Kiwako wouldn’t listen, saying, “If I don’t help, Japan will lose the war.” Ms. Morimoto said with regret, “We told my mother to let her go. We shouldn’t have said anything.”

After the bombing, Kiwako was found by her parents at Koi National School (now Koi Elementary School in Nishi Ward), where she had been taken. That evening, her family carried her on the panel of a wooden door back to their woodshed, where they had fled. Kiwako, burned all over her body, barely responded when family members called out her name.

That night, as the flames burning the delta threw light onto the mountains of the Koi district, Kiwako said, “It’s hard to breathe,” then passed away.

No photos of lost sister

Their father, Shigeo, also passed away at the age of 48, two years after the atomic bombing. Along with her mother and aunt, Ms. Morimoto used a wooden door as a table and sold cosmetics in front of Koi station (now Nishihiroshima station). To promote sales, she put on makeup for the first time. She felt both happy and dispirited.

Because their home had burned down in the atomic bombing, no photos remained of her lost sister. After she got married in 1954 and had two daughters, Ms. Morimoto went on managing the cosmetics business. When her daughters began attending school, she was invited to join study meetings organized by local mothers.

In 1965, she contributed her account, titled About My Sister, to a newsletter magazine. In it, she described the scene when her mother and her sister were weeping as they held hands. Yoshiro Mutsuoka, Ms. Morimoto’s aunt’s second son, was killed in the atomic bombing, too, when, like Kiwako, he was mobilized to help tear down homes to create a fire lane in Koami-cho. He was a first-year student at a municipal junior high school.

The Memorial Tower to the Mobilized Students was erected in the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park in 1967, and Ms. Morimoto took her daughters there and said, “This is the monument for your aunt and many others.” She also wrote about her A-bomb experience and her life in a number of testimonies. In the 2000s, at the invitation of the Japan Council against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs, she began conveying her account at the World Conference against Atomic & Hydrogen Bombs, held annually in the city of Hiroshima.

Ms. Morimoto said, “It’s been decades since I was here, but I’m glad I came.” She walked through Higashikanon-machi as if checking the route that her sister had taken that day long ago. According to the Record of the A-bomb Disaster, published by the City of Hiroshima in 1971, at least 217 students from Nishi Girls’ High School lost their lives in the atomic bombing.

(Originally published on July 14, 2015)