Hiroshima: 70 Years After the A-bombing: Message to the future; Mobilized as teenagers, senseless deaths

Jul. 24, 2015

The atomic bomb that was dropped on August 6, 1945 killed and injured men and women of all ages in an instant. Students who had been mobilized to demolish buildings for firebreaks were in open areas that provided no shelter. According to a 1966 study by Kiyoshi Shimizu, a professor at Hiroshima University who lost his 12-year-old son, 61.7 percent – nearly two thirds – of the students who had been put to work perished. This article takes a look at the personal effects of some of these students that were passed from their parents to their siblings and subsequently donated to the Peace Memorial Museum and describes the stories and memories associated with these items, which convey a message to the future.

Robbed of opportunity to learn

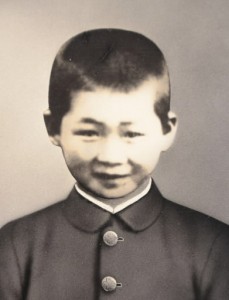

On August 6, 1945, Akira Sakanoue was 12 years old. The short-sleeved white shirt he wore that day is scorched from the left shoulder to the chest and covered in blood stains. He was also wearing a leather belt with a brass buckle.

“Those belongings are evidence of the era in which the government drove my brother and his schoolmates to their deaths,” said Akira’s brother, Takashi, 85, a resident of Hiroshima’s Nishi Ward, in a calm tone mixed with anger and a sense of loss. Akira was a first-year student at Hiroshima Municipal Junior High School (now Motomachi High School). Takashi was a fourth-year student there. When his brother did not return from his work site, Takashi walked the city in search of Akira, eventually finding him.

On August 6 Takashi was in Hatsukaichi, where the Mitsubishi Heavy Industries factory located in Minamikanon-machi (now part of Nishi Ward) had temporarily relocated. After seeing the flash of the A-bombing and the mushroom cloud that followed, Takashi and about 20 of his classmates set out for Hiroshima. With their skin hanging down, the people they passed along the way were so badly burned that Takashi and his classmates could hardly look at them.

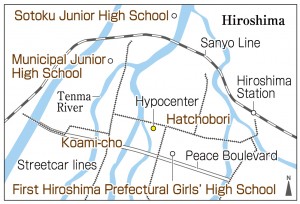

The Sakanoue home in Higashikanon-machi (now part of Nishi Ward) had burned, but Takashi’s parents were uninjured. His brother, however, was not there. Takashi set out amid the smoke for Koami-cho (now part of Naka Ward), where the first-year students at the Municipal Junior High School had been put to work demolishing buildings.

The next day as well he walked the burned-out city, going from Koi National School (now Koi Elementary School in Nishi Ward), which was being used as a relief station, to Furuta and on to Kusatsu National School. The following day he walked from Itsukaichi (now part of Saeki Ward) to the village of Ono (now part of the city of Hatsukaichi).

On August 9 Takashi found Akira, who was lying in a connecting corridor at the Ono Army Hospital. “My brother recognized me and smiled,” Takashi said. Akira recounted what had happened to him in a clear-headed manner. He and the other students had lined up before setting to work when they saw the flash of the atomic bomb. Akira and some friends headed for Koi. Along the way they were picked up by an army truck. He was given a tomato, which tasted really good.

Takashi headed back to Hiroshima, and his mother set off to see Akira, taking a change of clothes for him. But Akira’s condition rapidly deteriorated and he died that night.

“I couldn’t believe it,” Takashi recalled. At the time he could not have known that Akira had been exposed to a high dose of radiation.

According to “Requiem,” a publication issued in 2008 by surviving students of the Municipal Junior High School, all of the first- and second-year students who were sent to Koami-cho, about 800 meters from the hypocenter, died. A total of 315 of the school’s students died as a result of the A-bombing. Of those, the remains of 142 were never found.

Takashi graduated from the Municipal Junior High School in 1946. He worked for Hiroshima Prefecture and then for Chugoku Haiden (now Chugoku Electric Power Company), but he had difficulty carrying out his duties.

Takashi was mobilized when he was a second-year student at the Municipal Junior High School after the government issued an order requiring “volunteers” to engage in “vital work for the state.” Starting from his third year he spent the entire year working and was unable to study. Starting in 1949 he went to night school at Senda High School (now Hiroshima Municipal Technical High School), carving out a new future for himself in the postwar years.

Akira’s blood-stained shirt was donated to the Peace Memorial Museum by his father, Zensaku, in 1955 upon the opening of the facility. Takashi found Akira’s belt among his mother Kazu’s possessions in 1990. He took into account the feelings of his mother, who had held onto the belt, but ultimately donated it to the museum in the hope that allowing many people to see it would serve as a memorial to his brother.

Takashi said that even now, when he sees young people of junior high school age, he recalls the time when he and his brother had no choice but to be mobilized and ultimately separated by death.

Akira wrote an essay in which he said, “If I get into junior high school, I will become a great soldier.” The belongings of his younger brother, which carry his late parents’ sentiments as well, are imbued with Takashi’s strong desire. “After being robbed of the joy of learning, my brother and his classmates were robbed of their lives as well,” he said. “Such an era must never be allowed to come again. I want people to remember that.”

Fleeting joy of reunion

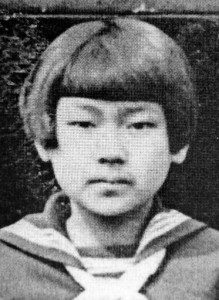

Thirteen-year-old Mikiyo Kimura recorded how she spent what proved to be her last Sunday, August 5, 1945, in her diary. She washed some of her things and, with her mother and elder sister, thoroughly cleaned the drawers and cupboards.

In her diary she wrote, “The weather was nice, so I washed my work pants, my uniform and my handkerchief. When I put on my stiff uniform, everyone laughed, saying I looked just like a scarecrow.” Mikiyo was the second girl in a family of six children. The family had moved to the area after her father, who worked for the national railway, was transferred to Hatsukaichi Station. They lived in an official residence next to the station.

The next morning Mikiyo, a first-year student at First Hiroshima Prefectural Girls’ High School (now Minami High School), headed off to work, wearing the clothing she had washed the day before. She and other students had been mobilized to demolish buildings in Koami-cho (now part of Naka Ward). She left her handkerchief behind.

Mikiyo’s elder sister, Taeko Matsuno, 86, a resident of Saeki Ward, recalled her sister’s final hours. “She could hardly open her eyes, but she couldn’t stop talking, I suppose because she was so happy to have come home to her family.”

Burned over her entire body, Mikiyo had jumped into the Tenma River to the west and was taken to Koi National School (now Koi Elementary School in Nishi Ward). A friend of Taeko’s found her there and told Taeko where her sister was.

Their father and other station workers carried Mikiyo home on a stretcher on the night of August 6. Taeko was working at a Mitsubishi Heavy Industries factory located in what is now Nishi Ward at the time of the A-bombing. She made it home that night and also sat up with Mikiyo. Taeko was a student at Yamanaka Girls’ High School (now the high school affiliated with Hiroshima University) in Senda-machi (now part of Naka Ward) and had been working as a mobilized student throughout the school year.

Amid her family’s desperate efforts to care for and encourage her, Mikiyo passed away on the morning of August 7. Just before dying, she turned to the east and put her hands together in prayer.

After the war, the family moved to Iwakuni in Yamaguchi Prefecture, where Taeko married and raised five daughters. She spoke little of her painful memories. But just before turning 80 she was seized with a desire to leave behind evidence of her sister’s life. She went through the belongings she had gotten from her parents: Mikiyo’s diary, her handkerchief, her drawings and calligraphy. There was also a badge identifying her as a member of the Student Corps from First Hiroshima Prefectural Girls’ High School.

Mikiyo’s diary began with this entry for April 7: “I’m so happy about getting to be a student at First Hiroshima Prefectural Girls’ High School that I mustn’t wake up too early in the morning.” Taeko donated the diary to the Peace Memorial Museum in 2009 along with that of her elder brother Kazuo.

At the time of the atomic bombing, Kazuo was enrolled at Hiroshima Technical Institute (now Hiroshima University in Senda-machi, Naka Ward). The following year he wrote in his diary, “The tragedy of the innocent young boys and girls will be forgotten over time.” Kazuo died in 1948 at the age of 21.

Taeko agreed to be interviewed for this article because she believes that “war, which mercilessly robs people of their futures, must never be repeated.” She had heart surgery last year and is not in good health. Taeko bought the handkerchief for Mikiyo at the Ise Grand Shrine while on a school trip with fellow students from Onaga Elementary School, located in what is now Higashi Ward. “She washed it, never imagining that she was going to die. It’s so sad.”

Precious gift, imbued with mother’s love

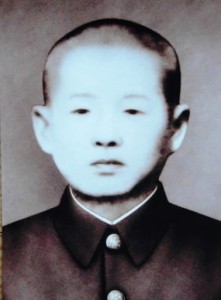

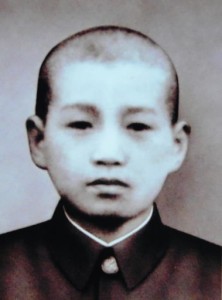

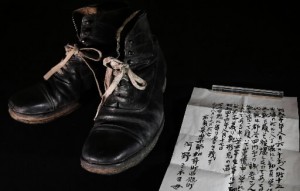

Masayoshi Kono, a 14-year-old second-year student at Sotoku Junior High School, and his brother Nobuo, 13, a first-year student at the school, were demolishing buildings in the Hatchobori area (now part of Naka Ward) at the time of the atomic bombing. Both boys, the first two sons in a family of six children, died as a result. Masayoshi died six days after the bombing at the family home in Kake-cho (now part of Akiota-cho in Hiroshima Prefecture). Nobuo was missing.

In 1969, the boys’ mother Mineyo donated the leather shoes Masayoshi had been wearing to the Peace Memorial Museum along with a brief note she wrote on a piece of stationery outlining her reasons for the donation. That year she had learned from the city’s list of unclaimed remains that remains believed to be those of Nobuo had been placed in the Atomic Bomb Memorial Mound. Nearly 25 years after the atomic bombing, she placed his ashes in a grave, achieving some closure.

In her note, Mineyo said, “These shoes belonged to my eldest son Masayoshi, who was wearing them while working as a mobilized student at the time of the atomic bombing.” The boys’ sister, Yasuko Sumiyoshi, 80, a resident of Asa Minami Ward, said this about the shoes: “I suppose my mother wanted her son, who attended school from the countryside, to have something nice. I sense her maternal love.” Leather shoes were hard to come by during the war. Mineyo had gotten Masayoshi’s shoes from wealthy relatives.

The boys’ father, Soichi, was a driver. Learning that something had happened in Hiroshima, he drove from Kake-cho to Hiroshima on the morning of August 7 to look for his sons. He went around to schools and the remains of work sites and found Masayoshi that evening at Hesaka National School (now Hesaka Elementary School in Higashi Ward).

Yasuko clearly recalls that Masayoshi’s back was badly burned. He could not move and repeatedly asked for water. Her parents did all they could to care for him.

Mineyo and Soichi were overcome with grief at the loss of their two sons. They used one Chinese character from the names of each of the boys in the names of two sons who were born after the war. Soichi was killed in an accident in 1949. Mineyo ran a grocery store and supported a family of nine that included the children’s grandparents.

The fate of Nobuo, whose remains had not been found, was learned when Masayoshi’s name appeared on the city’s list of unclaimed remains. Convinced that Nobuo had been wearing Masayoshi’s uniform, Mineyo went to collect the remains.

The family home was inherited by Yoshitaka, the next youngest brother, who is now 77. When he was growing up, Mineyo went to a local temple to pray every morning. On August 6 Yoshitaka accompanied his mother when she visited the Memorial Tower to the Mobilized Students in Peace Memorial Park. Mineyo lived to the age of 100.

In 2012, the year after Mineyo’s death, Yoshitaka donated the leather shoes to the Peace Memorial Museum along with the note his mother had written. “I would like them to convey my parents’ love and sadness,” he said.

According to a history published by Sotoku Gakuen on the 120th anniversary of the school’s founding, 512 students from the school died as a result of the atomic bombing. A total of 407 first- and second-year students who were at the work site in Hatchobori perished.

(Originally published on July 14, 2015)

■Blood-stained shirt

Robbed of opportunity to learn

On August 6, 1945, Akira Sakanoue was 12 years old. The short-sleeved white shirt he wore that day is scorched from the left shoulder to the chest and covered in blood stains. He was also wearing a leather belt with a brass buckle.

“Those belongings are evidence of the era in which the government drove my brother and his schoolmates to their deaths,” said Akira’s brother, Takashi, 85, a resident of Hiroshima’s Nishi Ward, in a calm tone mixed with anger and a sense of loss. Akira was a first-year student at Hiroshima Municipal Junior High School (now Motomachi High School). Takashi was a fourth-year student there. When his brother did not return from his work site, Takashi walked the city in search of Akira, eventually finding him.

On August 6 Takashi was in Hatsukaichi, where the Mitsubishi Heavy Industries factory located in Minamikanon-machi (now part of Nishi Ward) had temporarily relocated. After seeing the flash of the A-bombing and the mushroom cloud that followed, Takashi and about 20 of his classmates set out for Hiroshima. With their skin hanging down, the people they passed along the way were so badly burned that Takashi and his classmates could hardly look at them.

The Sakanoue home in Higashikanon-machi (now part of Nishi Ward) had burned, but Takashi’s parents were uninjured. His brother, however, was not there. Takashi set out amid the smoke for Koami-cho (now part of Naka Ward), where the first-year students at the Municipal Junior High School had been put to work demolishing buildings.

The next day as well he walked the burned-out city, going from Koi National School (now Koi Elementary School in Nishi Ward), which was being used as a relief station, to Furuta and on to Kusatsu National School. The following day he walked from Itsukaichi (now part of Saeki Ward) to the village of Ono (now part of the city of Hatsukaichi).

On August 9 Takashi found Akira, who was lying in a connecting corridor at the Ono Army Hospital. “My brother recognized me and smiled,” Takashi said. Akira recounted what had happened to him in a clear-headed manner. He and the other students had lined up before setting to work when they saw the flash of the atomic bomb. Akira and some friends headed for Koi. Along the way they were picked up by an army truck. He was given a tomato, which tasted really good.

Takashi headed back to Hiroshima, and his mother set off to see Akira, taking a change of clothes for him. But Akira’s condition rapidly deteriorated and he died that night.

“I couldn’t believe it,” Takashi recalled. At the time he could not have known that Akira had been exposed to a high dose of radiation.

According to “Requiem,” a publication issued in 2008 by surviving students of the Municipal Junior High School, all of the first- and second-year students who were sent to Koami-cho, about 800 meters from the hypocenter, died. A total of 315 of the school’s students died as a result of the A-bombing. Of those, the remains of 142 were never found.

Takashi graduated from the Municipal Junior High School in 1946. He worked for Hiroshima Prefecture and then for Chugoku Haiden (now Chugoku Electric Power Company), but he had difficulty carrying out his duties.

Takashi was mobilized when he was a second-year student at the Municipal Junior High School after the government issued an order requiring “volunteers” to engage in “vital work for the state.” Starting from his third year he spent the entire year working and was unable to study. Starting in 1949 he went to night school at Senda High School (now Hiroshima Municipal Technical High School), carving out a new future for himself in the postwar years.

Akira’s blood-stained shirt was donated to the Peace Memorial Museum by his father, Zensaku, in 1955 upon the opening of the facility. Takashi found Akira’s belt among his mother Kazu’s possessions in 1990. He took into account the feelings of his mother, who had held onto the belt, but ultimately donated it to the museum in the hope that allowing many people to see it would serve as a memorial to his brother.

Takashi said that even now, when he sees young people of junior high school age, he recalls the time when he and his brother had no choice but to be mobilized and ultimately separated by death.

Akira wrote an essay in which he said, “If I get into junior high school, I will become a great soldier.” The belongings of his younger brother, which carry his late parents’ sentiments as well, are imbued with Takashi’s strong desire. “After being robbed of the joy of learning, my brother and his classmates were robbed of their lives as well,” he said. “Such an era must never be allowed to come again. I want people to remember that.”

■Bearing witness

Fleeting joy of reunion

Thirteen-year-old Mikiyo Kimura recorded how she spent what proved to be her last Sunday, August 5, 1945, in her diary. She washed some of her things and, with her mother and elder sister, thoroughly cleaned the drawers and cupboards.

In her diary she wrote, “The weather was nice, so I washed my work pants, my uniform and my handkerchief. When I put on my stiff uniform, everyone laughed, saying I looked just like a scarecrow.” Mikiyo was the second girl in a family of six children. The family had moved to the area after her father, who worked for the national railway, was transferred to Hatsukaichi Station. They lived in an official residence next to the station.

The next morning Mikiyo, a first-year student at First Hiroshima Prefectural Girls’ High School (now Minami High School), headed off to work, wearing the clothing she had washed the day before. She and other students had been mobilized to demolish buildings in Koami-cho (now part of Naka Ward). She left her handkerchief behind.

Mikiyo’s elder sister, Taeko Matsuno, 86, a resident of Saeki Ward, recalled her sister’s final hours. “She could hardly open her eyes, but she couldn’t stop talking, I suppose because she was so happy to have come home to her family.”

Burned over her entire body, Mikiyo had jumped into the Tenma River to the west and was taken to Koi National School (now Koi Elementary School in Nishi Ward). A friend of Taeko’s found her there and told Taeko where her sister was.

Their father and other station workers carried Mikiyo home on a stretcher on the night of August 6. Taeko was working at a Mitsubishi Heavy Industries factory located in what is now Nishi Ward at the time of the A-bombing. She made it home that night and also sat up with Mikiyo. Taeko was a student at Yamanaka Girls’ High School (now the high school affiliated with Hiroshima University) in Senda-machi (now part of Naka Ward) and had been working as a mobilized student throughout the school year.

Amid her family’s desperate efforts to care for and encourage her, Mikiyo passed away on the morning of August 7. Just before dying, she turned to the east and put her hands together in prayer.

After the war, the family moved to Iwakuni in Yamaguchi Prefecture, where Taeko married and raised five daughters. She spoke little of her painful memories. But just before turning 80 she was seized with a desire to leave behind evidence of her sister’s life. She went through the belongings she had gotten from her parents: Mikiyo’s diary, her handkerchief, her drawings and calligraphy. There was also a badge identifying her as a member of the Student Corps from First Hiroshima Prefectural Girls’ High School.

Mikiyo’s diary began with this entry for April 7: “I’m so happy about getting to be a student at First Hiroshima Prefectural Girls’ High School that I mustn’t wake up too early in the morning.” Taeko donated the diary to the Peace Memorial Museum in 2009 along with that of her elder brother Kazuo.

At the time of the atomic bombing, Kazuo was enrolled at Hiroshima Technical Institute (now Hiroshima University in Senda-machi, Naka Ward). The following year he wrote in his diary, “The tragedy of the innocent young boys and girls will be forgotten over time.” Kazuo died in 1948 at the age of 21.

Taeko agreed to be interviewed for this article because she believes that “war, which mercilessly robs people of their futures, must never be repeated.” She had heart surgery last year and is not in good health. Taeko bought the handkerchief for Mikiyo at the Ise Grand Shrine while on a school trip with fellow students from Onaga Elementary School, located in what is now Higashi Ward. “She washed it, never imagining that she was going to die. It’s so sad.”

■Brother’s leather shoes

Precious gift, imbued with mother’s love

Masayoshi Kono, a 14-year-old second-year student at Sotoku Junior High School, and his brother Nobuo, 13, a first-year student at the school, were demolishing buildings in the Hatchobori area (now part of Naka Ward) at the time of the atomic bombing. Both boys, the first two sons in a family of six children, died as a result. Masayoshi died six days after the bombing at the family home in Kake-cho (now part of Akiota-cho in Hiroshima Prefecture). Nobuo was missing.

In 1969, the boys’ mother Mineyo donated the leather shoes Masayoshi had been wearing to the Peace Memorial Museum along with a brief note she wrote on a piece of stationery outlining her reasons for the donation. That year she had learned from the city’s list of unclaimed remains that remains believed to be those of Nobuo had been placed in the Atomic Bomb Memorial Mound. Nearly 25 years after the atomic bombing, she placed his ashes in a grave, achieving some closure.

In her note, Mineyo said, “These shoes belonged to my eldest son Masayoshi, who was wearing them while working as a mobilized student at the time of the atomic bombing.” The boys’ sister, Yasuko Sumiyoshi, 80, a resident of Asa Minami Ward, said this about the shoes: “I suppose my mother wanted her son, who attended school from the countryside, to have something nice. I sense her maternal love.” Leather shoes were hard to come by during the war. Mineyo had gotten Masayoshi’s shoes from wealthy relatives.

The boys’ father, Soichi, was a driver. Learning that something had happened in Hiroshima, he drove from Kake-cho to Hiroshima on the morning of August 7 to look for his sons. He went around to schools and the remains of work sites and found Masayoshi that evening at Hesaka National School (now Hesaka Elementary School in Higashi Ward).

Yasuko clearly recalls that Masayoshi’s back was badly burned. He could not move and repeatedly asked for water. Her parents did all they could to care for him.

Mineyo and Soichi were overcome with grief at the loss of their two sons. They used one Chinese character from the names of each of the boys in the names of two sons who were born after the war. Soichi was killed in an accident in 1949. Mineyo ran a grocery store and supported a family of nine that included the children’s grandparents.

The fate of Nobuo, whose remains had not been found, was learned when Masayoshi’s name appeared on the city’s list of unclaimed remains. Convinced that Nobuo had been wearing Masayoshi’s uniform, Mineyo went to collect the remains.

The family home was inherited by Yoshitaka, the next youngest brother, who is now 77. When he was growing up, Mineyo went to a local temple to pray every morning. On August 6 Yoshitaka accompanied his mother when she visited the Memorial Tower to the Mobilized Students in Peace Memorial Park. Mineyo lived to the age of 100.

In 2012, the year after Mineyo’s death, Yoshitaka donated the leather shoes to the Peace Memorial Museum along with the note his mother had written. “I would like them to convey my parents’ love and sadness,” he said.

According to a history published by Sotoku Gakuen on the 120th anniversary of the school’s founding, 512 students from the school died as a result of the atomic bombing. A total of 407 first- and second-year students who were at the work site in Hatchobori perished.

(Originally published on July 14, 2015)