Hiroshima: 70 Years After the A-bombing: A-bomb survivors in South Korea ask Japan to take responsibility for the past

Jun. 1, 2015

Japanese governments have called Japan “the only A-bombed nation.” However, doesn’t this overlook Koreans who experienced the atomic bombings after being forcibly brought from the Korean Peninsula or were conscripted into the Japanese military as well as those who immigrated to Japan under Japan’s colonial rule? For many years, Japanese administrations have ignored calls for support for the Korean survivors. In South Korea, 2,561 A-bomb survivors are alive today, the highest number in any nation overseas, and the majority experienced the Hiroshima bombing. The distress of A-bomb survivors living in South Korea and North Korea, who endured the A-bomb attack on August 6, 1945, and existing documents call for Japan, which stresses the inhumanity of the atomic bombings, to take responsibility and pay redress for the past.

The founder of the South Korea A-Bomb Sufferers Association, Kwak Kwi Hoon, 90, who lives in Seongnam-si, Gyeonggi-do, is now honorary president. With the miseries of the atomic bombings in mind, Mr. Kwak felt he had no choice but to fight Japan’s injustice.

“A-bomb survivors are A-bomb survivors, no matter where they are,” he argued. In 2002, Mr. Kwak won his case in court and the Japanese government said it would not appeal. Directive No. 402, which was issued by the former Health and Welfare Ministry in 1974, had stipulated that Korean A-bomb survivors who remained in Japan could receive a health management allowance, but once they left Japan, they would forfeit this benefit. Mr. Kwak spearheaded the campaign to abolish this arbitrary provision, which paved the way for A-bomb survivors living in the United States and Brazil to also access relief measures.

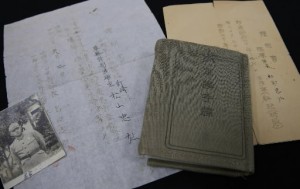

Mr. Kwak’s long battle against injustice began after he was brought to Hiroshima. When he was in his fifth year at Jeonju National Normal School in 1944, he was drafted into the Japanese military under a conscription order for the Korean people. His military handbook, which confirms his survivor status, is held in the Independence Hall of Korea (located in Cheonan-si, Chungcheongnam-do), which displays artifacts of Korean history.

The military handbook of “Tadahiro Matsuyama,” which was the Japanese name assigned to Mr. Kwak by Imperial Japan, contains the details of his military record, like “On September 10, 1944, as an active soldier of the Western Army, in the second military unit...”

Mr. Kwak looked grimly at his military record, saying that, beyond the fact that Koreans were forced to affirm their loyalty to the Japanese emperor, their very lives were put at stake, and he had lived in despair.

He was the eldest son of six siblings. Bearing the hopes of his family, he advanced in his education and came to speak fluent Japanese. When he entered the military, he was selected as a special officer candidate.

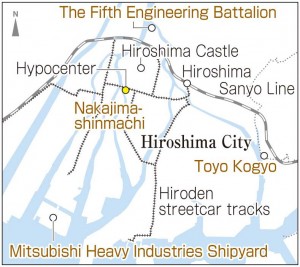

On August 6, 1945, he was exposed to the atomic bombing while out in the open at the military base of the fifth engineering battalion (now part of Naka Ward), about two kilometers from the hypocenter. The next thing he knew, his back was burning. Japanese soldiers who had become friendly comrades died before his eyes. He decided that he would fight to survive, up to his last breath.

He was taken to a branch of an army hospital set up at a national school in the village of Ono (now Hatsukaichi City), and heard the emperor’s radio broadcast on August 15. “Banzai!” said Mr. Kwak, as the emperor revealed Japan’s surrender. He was overwhelmed with pent-up emotion and wept. In September, he returned to his homeland with an A-bomb victim certificate which said that he had developed malignant anemia.

After that, he relearned Korean, which he could not use in Japan, and became a teacher. He shared his A-bomb account with a newspaper in 1959, after an armistice agreement for the Korean War, and became South Korea’s first A-bomb witness. He lobbied Japan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs to negotiate for compensation.

However, in the Treaty on Basic Relations between Japan and the Republic of Korea, which established normal diplomatic relations in 1965, relief efforts for A-bomb survivors were ignored even by the Korean government.

In 1967, Mr. Kwak visited Hiroshima again and learned that the Atomic Bomb Medical Relief Law was established in 1957 (now the Atomic Bomb Survivors Relief Law), and he worked to found the South Korean Atomic Bomb Sufferers Association. He recalled how Korean A-bomb survivors back then became destitute and quarreled constantly among themselves. Mr. Kwak threw himself into relief efforts to assist the Korean A-bomb survivors.

When he came to Japan in 1974 to seek compensation for conscripted laborers of the former Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, he applied for the Atomic Bomb Survivor’s Certificate with the City of Hiroshima, but was rejected. In 1979, he received the survivor’s certificate which officially recognized him as an A-bomb survivor. However, because of Directive No. 402, he was unable to access benefits equivalent to those received by survivors living in Japan.

He said he was thrilled when he won his lawsuit against the Japanese government in 2002. Still, he is troubled by the fact that when the Japanese government is asked about Japan’s colonial rule and war responsibility, a pledge is made to meet its obligations from a humanitarian standpoint, but an apology is not forthcoming. He wonders why the Japanese government does not frankly admit the nation’s misdeeds because, even today, injustice lingers. For A-bomb survivors living overseas, though they are survivors like those residing in Japan, there is a ceiling on the coverage for their health care costs.

Two years ago, Mr. Kwak published a 283-page memoir titled I Am a Korean A-bomb Survivor. In the book he describes his life as an activist, struggling against the Japanese and Korean governments, as well as the support he received from Japanese citizens.

He believes that understanding the true facts of the history between the two countries, including the plight of Korean A-bomb survivors and the support given to them by Japanese citizens, will lead to reconciliation. As such conditions are established, the Korean people, who tend to think the A-bombings liberated Korea from Japanese colonial rule, will then be ready to accept the indisputable fact that nuclear arms are supremely inhumane weapons and must be eliminated. He plans to write the Japanese version of his memoir this summer, which marks the 70th anniversary of the atomic bombing, so that the Japanese people will be aware of the significance of the lawsuit won through the cooperation of Korean and Japanese citizens.

Ha Wineon, 86, experienced the atomic bombing as a mobilized student in Hiroshima. When asked for an interview, she first said that she had forgotten Japanese, but, in fact, it has lingered in her memory. She now lives in an apartment overlooking the busy port of the city of Busan with her second son and his wife.

She began to recount the days which led up to her encounter with the atomic bomb in a foreign nation, saying that, while in Japan, she was known as Shigeko Kawamura and her brother was called Masao.

Ms. Ha’s hometown was Hapcheon-gun, Gyeongsangnam-do. In the prewar Korean community in Hiroshima, there were so many people from Hapcheon that it was said, “You need to ask their names, but you don’t need to ask where they’re from.” Men living in the mountain areas of Hapcheon left after Japan annexed Korea in 1910, coming to Hiroshima to engage in construction work, including work at the Ota River. Before long, they sent for their families, and the number of permanent Korean residents in the city soon rose.

Ms. Ha said that her father had worked for a county office. First, her two uncles moved to Hiroshima and founded a transport company, then her mother, her younger brother, and her grandparents followed. Their home was in Fuchu-cho near Toyo Kogyo (now Mazda Motor Corporation). She entered the fourth grade, one grade behind, at Fuchu Elementary School and learned Japanese.

In 1942, one year after the outbreak of the Pacific War between Japan and the United States, she entered Kaita Girls’ High School. According to a commemorative publication for the 30th anniversary of Kaita Senior High School, the first 100 students to enter the school manufactured firearms at Toyo Kogyo from October 1944, in line with an order which mobilized students for the war effort. Ms. Ha commuted by train from the city of Iwakuni, where her family had moved because of her father’s work, and each day operated an engine lathe or drilling machine.

She said the work left her covered in oil. This was during Japan’s empire-building era, and she was forced to use the name Shigeko Kawamura.

The atomic bomb exploded after she had changed into her work clothes and switched on her machine. Everything went black, then she came to and heard the sounds of a voice calling “Get in the shelter!” and other students’ footsteps. Around 5 p.m., led by a mobilized university student, she managed to reach Onaga-cho (now Higashi Ward), where her aunt and uncle were living. Her parents came by truck to get her, but her brother, who was three years younger, did not come.

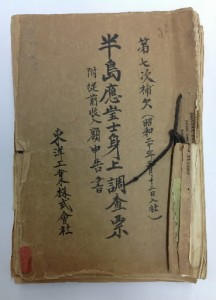

Ms. Ha took out a document, for which she had written a letter and obtained in 1994. “This is my brother’s certificate,” she said. Bearing the name of the principal of Hiroshima Prefectural Hiroshima Technical High School, it reads: “Masao Kawamura, first-year student in the electrical department, Hiroshima Prefectural Hiroshima Technical High School. Mobilized as a student volunteer on August 6, 1945 in Nakajima-shinmachi, Hiroshima City…”

Her brother, whose real name was Chandu, was killed while working outdoors, helping to dismantle buildings to create a fire lane in the southern part of what is now the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park. On August 7, Ms. Ha and her father found Chandu’s remains at the site. His internal organs had ruptured from his body.

Ms. Ha said that her father and mother wept without end and the family returned to Korea from Yamaguchi Prefecture in an illegal boat that fall after Korea regained its independence from Japan. The next year she wed an elementary school teacher and they had three sons and two daughters. During the Korean War, which broke out in 1950, a fierce battle was fought in Hapcheon, and their family register, which included her brother who perished in Hiroshima, was lost to the flames. In 1994, one year before the 50th anniversary of South Korea’s independence, she used her brother’s Japanese name and the name of his school to confirm his death, because she also sought to prove her own experience of the atomic bombing.

She obtained the Atomic Bomb Survivor’s Certificate from the City of Hiroshima in September 2003, the year after the Health, Labour and Welfare Ministry lost the lawsuit filed by Kwak Kwi Hoon and began to provide health care allowances to A-bomb survivors overseas. Ms. Ha visited Hiroshima and met some of her old schoolmates after an interval of 58 years.

She beamed, saying, “My former classmate verified my story.” Then an apologetic look crossed her face and she said, “I’d like to see them again, but my legs are now weak.”

As for her experience of the atomic bombing, she said, “I’ve told my husband and friends that I saw badly-mangled bodies.” When asked how they responded, she gave a sigh and grew thoughtful. “Some people feel sorry for me,” was all she said.

The Korean people feel that the atomic bombings were the result of the war that Japan had waged and that they had nothing to do with the attacks. This perception of history is deeply rooted in South Korea, and Ms. Ha can’t help but feel a widening gap between South Korea and Japan when it comes to views of the atomic bombings.

How many Koreans experienced the atomic bombings? There are various estimates, but the entire picture is still unclear.

According to Hiroshima and Nagasaki, a volume edited by the A-bombed cities and published in 1979, the number of Korean A-bomb victims and survivors is estimated to be 25,000-28,000 in Hiroshima and 11,500-12,000 in Nagasaki.

In the first investigation of this matter, which was undertaken by the Korean Ministry of Social Health in 1990, the number of A-bomb survivors came to 2,307, and of this number, 91 percent experienced the atomic bombing in Hiroshima. Directive No. 402 was struck down in Japan in 2003, and survivors took this opportunity to apply, one after another, for the Atomic Bomb Survivor’s Certificate.

According to an assessment of applicants made by the Korean Red Cross, as of the end of March, 2,471 people now hold the Atomic Bomb Survivor’s Certificate and another 90 have not yet obtained the certificate due to difficulties in finding witnesses to verify their experience, though they have already been recognized as A-bomb sufferers by the Korean Red Cross.

It was estimated that 928 A-bomb survivors were living in North Korea, as of 2002, but they were exempt from accessing services under the Atomic Bomb Survivors Relief Law because Japan has no diplomatic relations with North Korea.

(Originally published on May 11, 2015)

Kwak Kwi Hoon : Fight against injustice paves way for relief efforts

The founder of the South Korea A-Bomb Sufferers Association, Kwak Kwi Hoon, 90, who lives in Seongnam-si, Gyeonggi-do, is now honorary president. With the miseries of the atomic bombings in mind, Mr. Kwak felt he had no choice but to fight Japan’s injustice.

“A-bomb survivors are A-bomb survivors, no matter where they are,” he argued. In 2002, Mr. Kwak won his case in court and the Japanese government said it would not appeal. Directive No. 402, which was issued by the former Health and Welfare Ministry in 1974, had stipulated that Korean A-bomb survivors who remained in Japan could receive a health management allowance, but once they left Japan, they would forfeit this benefit. Mr. Kwak spearheaded the campaign to abolish this arbitrary provision, which paved the way for A-bomb survivors living in the United States and Brazil to also access relief measures.

Mr. Kwak’s long battle against injustice began after he was brought to Hiroshima. When he was in his fifth year at Jeonju National Normal School in 1944, he was drafted into the Japanese military under a conscription order for the Korean people. His military handbook, which confirms his survivor status, is held in the Independence Hall of Korea (located in Cheonan-si, Chungcheongnam-do), which displays artifacts of Korean history.

The military handbook of “Tadahiro Matsuyama,” which was the Japanese name assigned to Mr. Kwak by Imperial Japan, contains the details of his military record, like “On September 10, 1944, as an active soldier of the Western Army, in the second military unit...”

Mr. Kwak looked grimly at his military record, saying that, beyond the fact that Koreans were forced to affirm their loyalty to the Japanese emperor, their very lives were put at stake, and he had lived in despair.

He was the eldest son of six siblings. Bearing the hopes of his family, he advanced in his education and came to speak fluent Japanese. When he entered the military, he was selected as a special officer candidate.

On August 6, 1945, he was exposed to the atomic bombing while out in the open at the military base of the fifth engineering battalion (now part of Naka Ward), about two kilometers from the hypocenter. The next thing he knew, his back was burning. Japanese soldiers who had become friendly comrades died before his eyes. He decided that he would fight to survive, up to his last breath.

He was taken to a branch of an army hospital set up at a national school in the village of Ono (now Hatsukaichi City), and heard the emperor’s radio broadcast on August 15. “Banzai!” said Mr. Kwak, as the emperor revealed Japan’s surrender. He was overwhelmed with pent-up emotion and wept. In September, he returned to his homeland with an A-bomb victim certificate which said that he had developed malignant anemia.

After that, he relearned Korean, which he could not use in Japan, and became a teacher. He shared his A-bomb account with a newspaper in 1959, after an armistice agreement for the Korean War, and became South Korea’s first A-bomb witness. He lobbied Japan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs to negotiate for compensation.

However, in the Treaty on Basic Relations between Japan and the Republic of Korea, which established normal diplomatic relations in 1965, relief efforts for A-bomb survivors were ignored even by the Korean government.

In 1967, Mr. Kwak visited Hiroshima again and learned that the Atomic Bomb Medical Relief Law was established in 1957 (now the Atomic Bomb Survivors Relief Law), and he worked to found the South Korean Atomic Bomb Sufferers Association. He recalled how Korean A-bomb survivors back then became destitute and quarreled constantly among themselves. Mr. Kwak threw himself into relief efforts to assist the Korean A-bomb survivors.

When he came to Japan in 1974 to seek compensation for conscripted laborers of the former Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, he applied for the Atomic Bomb Survivor’s Certificate with the City of Hiroshima, but was rejected. In 1979, he received the survivor’s certificate which officially recognized him as an A-bomb survivor. However, because of Directive No. 402, he was unable to access benefits equivalent to those received by survivors living in Japan.

He said he was thrilled when he won his lawsuit against the Japanese government in 2002. Still, he is troubled by the fact that when the Japanese government is asked about Japan’s colonial rule and war responsibility, a pledge is made to meet its obligations from a humanitarian standpoint, but an apology is not forthcoming. He wonders why the Japanese government does not frankly admit the nation’s misdeeds because, even today, injustice lingers. For A-bomb survivors living overseas, though they are survivors like those residing in Japan, there is a ceiling on the coverage for their health care costs.

Two years ago, Mr. Kwak published a 283-page memoir titled I Am a Korean A-bomb Survivor. In the book he describes his life as an activist, struggling against the Japanese and Korean governments, as well as the support he received from Japanese citizens.

He believes that understanding the true facts of the history between the two countries, including the plight of Korean A-bomb survivors and the support given to them by Japanese citizens, will lead to reconciliation. As such conditions are established, the Korean people, who tend to think the A-bombings liberated Korea from Japanese colonial rule, will then be ready to accept the indisputable fact that nuclear arms are supremely inhumane weapons and must be eliminated. He plans to write the Japanese version of his memoir this summer, which marks the 70th anniversary of the atomic bombing, so that the Japanese people will be aware of the significance of the lawsuit won through the cooperation of Korean and Japanese citizens.

Ha Wineon: Seeking witnesses in a foreign land

Ha Wineon, 86, experienced the atomic bombing as a mobilized student in Hiroshima. When asked for an interview, she first said that she had forgotten Japanese, but, in fact, it has lingered in her memory. She now lives in an apartment overlooking the busy port of the city of Busan with her second son and his wife.

She began to recount the days which led up to her encounter with the atomic bomb in a foreign nation, saying that, while in Japan, she was known as Shigeko Kawamura and her brother was called Masao.

Ms. Ha’s hometown was Hapcheon-gun, Gyeongsangnam-do. In the prewar Korean community in Hiroshima, there were so many people from Hapcheon that it was said, “You need to ask their names, but you don’t need to ask where they’re from.” Men living in the mountain areas of Hapcheon left after Japan annexed Korea in 1910, coming to Hiroshima to engage in construction work, including work at the Ota River. Before long, they sent for their families, and the number of permanent Korean residents in the city soon rose.

Ms. Ha said that her father had worked for a county office. First, her two uncles moved to Hiroshima and founded a transport company, then her mother, her younger brother, and her grandparents followed. Their home was in Fuchu-cho near Toyo Kogyo (now Mazda Motor Corporation). She entered the fourth grade, one grade behind, at Fuchu Elementary School and learned Japanese.

In 1942, one year after the outbreak of the Pacific War between Japan and the United States, she entered Kaita Girls’ High School. According to a commemorative publication for the 30th anniversary of Kaita Senior High School, the first 100 students to enter the school manufactured firearms at Toyo Kogyo from October 1944, in line with an order which mobilized students for the war effort. Ms. Ha commuted by train from the city of Iwakuni, where her family had moved because of her father’s work, and each day operated an engine lathe or drilling machine.

She said the work left her covered in oil. This was during Japan’s empire-building era, and she was forced to use the name Shigeko Kawamura.

The atomic bomb exploded after she had changed into her work clothes and switched on her machine. Everything went black, then she came to and heard the sounds of a voice calling “Get in the shelter!” and other students’ footsteps. Around 5 p.m., led by a mobilized university student, she managed to reach Onaga-cho (now Higashi Ward), where her aunt and uncle were living. Her parents came by truck to get her, but her brother, who was three years younger, did not come.

Ms. Ha took out a document, for which she had written a letter and obtained in 1994. “This is my brother’s certificate,” she said. Bearing the name of the principal of Hiroshima Prefectural Hiroshima Technical High School, it reads: “Masao Kawamura, first-year student in the electrical department, Hiroshima Prefectural Hiroshima Technical High School. Mobilized as a student volunteer on August 6, 1945 in Nakajima-shinmachi, Hiroshima City…”

Her brother, whose real name was Chandu, was killed while working outdoors, helping to dismantle buildings to create a fire lane in the southern part of what is now the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park. On August 7, Ms. Ha and her father found Chandu’s remains at the site. His internal organs had ruptured from his body.

Ms. Ha said that her father and mother wept without end and the family returned to Korea from Yamaguchi Prefecture in an illegal boat that fall after Korea regained its independence from Japan. The next year she wed an elementary school teacher and they had three sons and two daughters. During the Korean War, which broke out in 1950, a fierce battle was fought in Hapcheon, and their family register, which included her brother who perished in Hiroshima, was lost to the flames. In 1994, one year before the 50th anniversary of South Korea’s independence, she used her brother’s Japanese name and the name of his school to confirm his death, because she also sought to prove her own experience of the atomic bombing.

She obtained the Atomic Bomb Survivor’s Certificate from the City of Hiroshima in September 2003, the year after the Health, Labour and Welfare Ministry lost the lawsuit filed by Kwak Kwi Hoon and began to provide health care allowances to A-bomb survivors overseas. Ms. Ha visited Hiroshima and met some of her old schoolmates after an interval of 58 years.

She beamed, saying, “My former classmate verified my story.” Then an apologetic look crossed her face and she said, “I’d like to see them again, but my legs are now weak.”

As for her experience of the atomic bombing, she said, “I’ve told my husband and friends that I saw badly-mangled bodies.” When asked how they responded, she gave a sigh and grew thoughtful. “Some people feel sorry for me,” was all she said.

The Korean people feel that the atomic bombings were the result of the war that Japan had waged and that they had nothing to do with the attacks. This perception of history is deeply rooted in South Korea, and Ms. Ha can’t help but feel a widening gap between South Korea and Japan when it comes to views of the atomic bombings.

The number of Korean survivors is unclear

How many Koreans experienced the atomic bombings? There are various estimates, but the entire picture is still unclear.

According to Hiroshima and Nagasaki, a volume edited by the A-bombed cities and published in 1979, the number of Korean A-bomb victims and survivors is estimated to be 25,000-28,000 in Hiroshima and 11,500-12,000 in Nagasaki.

In the first investigation of this matter, which was undertaken by the Korean Ministry of Social Health in 1990, the number of A-bomb survivors came to 2,307, and of this number, 91 percent experienced the atomic bombing in Hiroshima. Directive No. 402 was struck down in Japan in 2003, and survivors took this opportunity to apply, one after another, for the Atomic Bomb Survivor’s Certificate.

According to an assessment of applicants made by the Korean Red Cross, as of the end of March, 2,471 people now hold the Atomic Bomb Survivor’s Certificate and another 90 have not yet obtained the certificate due to difficulties in finding witnesses to verify their experience, though they have already been recognized as A-bomb sufferers by the Korean Red Cross.

It was estimated that 928 A-bomb survivors were living in North Korea, as of 2002, but they were exempt from accessing services under the Atomic Bomb Survivors Relief Law because Japan has no diplomatic relations with North Korea.

(Originally published on May 11, 2015)