Hiroshima: 70 Years After the A-bombing: Silent witnesses; painful partings; tell future generations of the A-bombing

Apr. 21, 2015

By the end of 1945, approximately 140,000 people, young and old alike, had died as a result of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima. Many of those who survived lost parents, siblings and children in the A-bombing. This article takes a look at some of the materials in the collection of the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, which will mark the 60th anniversary of its opening this summer. These items, which underwent painful partings from their owners, provide evidence of the existence of those to whom they belonged and carry the abiding feelings of their families. These “silent witnesses” tell of the consequences of the use of nuclear weapons.

Thoughts of family as she polishes them

Sonoko Nishimura, 85, a resident of Higashi Hiroshima, held up five tarnished coins, two 1-sen coins, a 10-sen coin, a 50-sen coin and a copper coin, as she stood at the site of her former home next to the Funairi Honmachi stop on the Eba streetcar line in Hiroshima’s Naka Ward. “Unfortunately, this is all I have left to remember my parents by,” she said in a bright tone, though her eyes were wet with tears.

Her father, Ichiji Himaru, 56, and mother, Toshiko, 55, lived and worked at a dormitory for a technician training center of the Chugoku Branch of the Japan Electric and Transmission Company (now Chugoku Electric Co.) in Funairi Honmachi, providing meals for the dormitory’s 90 teenage residents. Fifteen-year-old Sonoko was the youngest of six children and the only one still living with her parents. She was employed at the field shipping workshop in Ujina-cho (now part of Minami Ward).

On the morning of August 6, 1945, Toshiko helped her daughter tie her canvas shoes and sent her off to work saying, “Be someone people can love.” That was the last time Sonoko saw her mother.

The two-story wooden dormitory building, which was about 1.6 km from the hypocenter, collapsed and burned. Sonoko was at the shipping workshop at the time of the atomic bombing. She fled to Kanawajima Island just offshore and spent a sleepless night among the injured who were brought there. The next day, accompanied by an official, she went by boat from Ujina Port to Eba-machi and looked for her parents, but she could learn nothing of their fate. Her eldest brother Ikuro, 35, who worked at the Kure Naval Arsenal, came to get her on August 9, and they then headed back to the site of the dormitory.

“A resident of the dorm who had survived and returned to the site bowed to us,” she said. The young man told them that Ichiji had been trapped in the building’s front entrance and had called for help, but the flames were approaching, and he could not pull Ichiji out. Sonoko and her brother dug at the spot and found Ichiji’s skeletal remains. Toshiko’s body was lying nearby.

The five coins were found near the air raid shelter that Ichiji, who was disabled, had dug next to the dormitory. Ichiji had kept the copper coin, of a type that had been made until the mid-19th Century, as a memento of his own mother.

After the war Ms. Nishimura relied on the help of relatives and worked in a textile mill in Miyoshi, Hiroshima Prefecture. She lived in a dormitory where she kept the coins in a sewing basket her brother had made for her. She sometimes took them out to polish them. She thought of them as a sort of amulet from her parents. After she married at the age of 22, she put the coins in the Buddhist altar of her new home. She took them out every August 6 and recalled her parents.

She donated the five coins to the museum in 2009 after the death of her husband. She lives next door to her son and his wife, and said she had begun to feel her age. She is the only one of the children in her family who is still living.

“When I hold these coins, I recall what I saw and felt when we gathered up my father’s remains,” Ms. Nishimura said. “I lost my parents to the atomic bombing and was left with almost nothing to remember them by. I would like future generations to know as much as possible about the A-bombing.” Including her parents, a total of 26 people were killed at the dormitory. Few people are left who know the facts of the atomic bombing, and her desire to convey the facts through the coins remains unchanged.

Hope that tragedy is never repeated

A bag containing the lunchbox and canteen of Shigeru Orimen, 13, a first-year-student at Hiroshima Second Middle School (now Kanon High School) was found by his mother along with his nearly unrecognizable body. His charred canteen has traveled to New York, where it will be displayed in an exhibition on the atomic bombing being put on by the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki starting April 27. The exhibition will move to Washington, D.C. in June.

On August 6 the first-year students of Hiroshima Second Middle School gathered on the bank of the Honkawa River, which runs alongside what is now Peace Memorial Park, and prepared to demolish buildings to make fire breaks. The site was about 500 meters from the spot at which the atomic bomb exploded. A total of 321 students were killed.

Shigeru’s mother Shigeko, who died in 1996 at the age of 88, came to the city from the village of Yahata (now part of Saeki Ward, Hiroshima) to look for him. Her husband had been drafted. On August 9 she found Shigeru’s face-down remains near the spot where the students had been working. With him was the bag containing his hand-me-down aluminum lunchbox, which bore the name of his elder brother Masaaki, and his canteen.

“When my mother looked at my brother’s belongings, she would weep and say, ‘Poor thing. He didn’t even get to eat his lunch,’” Shigeru’s younger brother Akio, 79, a resident of Saeki Ward, recalled. At the time of the atomic bombing, Akio was a fourth grader at a national school. He helped provide aid to victims who fled to Yahata. “My brother’s death, the miserable state of the injured – those things motivated me to become a doctor,” he said.

In 1967, Akio, who had become an inzternist, got involved in work for a health center run by what is now the Hiroshima Atomic Bomb Casualty Council in Naka Ward. He also served as secretary of the Hiroshima International Council for the Radiation-exposed, which was formed by Hiroshima Prefecture and others in 1991.

Akio spoke of the sadness the atomic bombing brought on his family and the frightful effects of radiation on the human body. “I’m sure my mother would have gladly sent my brother’s belongings to the U.S. if she believed they would convey those things to the people there,” he said. Shigeru’s mother donated his canteen and lunchbox to the Peace Memorial Museum in 1962. Akio believes it was her hope that the tragedy of the atomic bombing never be repeated.

Substitute for remains; wiped it every morning

Miyoko Osugi, 13, was a first-year student at Hiroshima Municipal Girls’ High School (now Funairi High School) on the day of the atomic bombing. That day she left the family home in Minami-machi (now part of Minami Ward) wearing a pair of wooden clogs. Despite the passage of time, the outline of Miyoko’s foot and some writing in ink later added by her mother Tomiko, who died in 1971 at the age of 67, are still faintly visible on Miyoko’s left clog.

A total of 541 first- and second-year students from the school were in an area from the former Kobiki-cho to the bank of the Motoyasu River, south of what is now the Peace Memorial Museum, to work on the demolition of buildings to create fire breaks. All of them were killed in the A-bombing.

Tomiko and Miyoko’s brother Teruaki, an employee of the Hiroshima Railway Bureau, looked for Miyoko, but could not find her. Tomiko, however, walked the area where the students had been working and two months later found one of Miyoko’s clogs under a burned roof tile not far from the site. She recognized the clog from the thong, which she had made from one of her kimonos.

“Miyoko’s remains were never found, so my mother-in-law treasured the clog instead,” said Teruaki’s widow Nobuko, 80, a resident of Nishi Ward, recalling time she spent with Tomiko. Nobuko married Teruaki in 1960 and Tomiko lived with the couple. Teruaki died in 2011 at the age of 84. Tomiko carefully wiped the clog every morning and recited a sutra, Nobuko said. Tomiko talked about her recollections of Miyoko to Nobuko and lamented Miyoko’s death at such a young age.

Tomiko donated the clog to the museum in 1963. She hesitated to do so, saying she would miss it, but Teruaki persuaded her to donate it. “He told her everyone would be able to understand the family’s sadness,” Nobuko said.

A publication called “Floating Lanterns” was compiled by parents of students from the Hiroshima Municipal Girls’ High School in their memory. For Volume 4, which was published in 1996, Teruaki wrote: “If I had taken your place, oh, baby sister.” These sentiments are shared by his 52-year-old son who lives in Hagi, Yamaguchi Prefecture. Now, in the summer, accompanied by two grandchildren, Nobuko says a silent prayer at the family grave where Miyoko also rests and the monument to the students of Hiroshima Municipal Girls’ High School along the bank of the Motoyasu River.

“I’m sure my mother-in-law and husband will rest in peace if people think of the senselessness of war when they see the wooden clog,” Nobuko said. The clog, which had great significance for the family, is on display in the Peace Memorial Museum. The museum attracts 1.38 million visitors annually.

Kind mother; dress carries hopes

When she and her mother fled after the atomic bombing, Futaba Takase, 87, now a resident of Tokyo, was wearing a dress her mother had made for her. Amid the shortage of supplies during the war, her mother had been able to get hold of some meisen silk cloth, from which she made the dress.

On the day of the atomic bombing, Futaba was with her mother, Setsuko Mito, 38, and her 15-year-old sister at the home of a relative in Ote-machi. Her father, who worked for the Ministry of Transportation and Communications, had died, and Futaba had moved with her family to her parents’ hometown of Hiroshima on July 26 to escape air raids in Tokyo.

Their home was approximately 1.2 km from the hypocenter. Futaba, her mother and sister were trapped under the house when it collapsed. “My mother had a piece of wood stuck in her leg. She pulled it out herself, and then removed the wood that was on top of me,” Ms. Takase said. But her mother was seriously injured. The two girls supported their mother, one on each side, and the three of them fled to Kanawajima Island. From there they were taken to Kuba National School (in what is now the city of Otake) on a military ship and temporarily housed there.

Setsuko was by then only half conscious, and she died on September 1. Futaba was still wearing the dress her mother had made for her. Setsuko’s last words were: “I want to see my son, but it’s too late.” Her son, Akimoto, 11, had already entered the elementary school affiliated with the Hiroshima Higher Normal School and had been evacuated to the northern part of the prefecture with other children. He did not return until September 3. At the end of October, Futaba set off for the home of her aunt in Okayama with little more than the clothes on her back. Her face was swollen, and she was suffering from diarrhea.

Five years after the atomic bombing, she married. She and her husband, an employee of the Bank of Japan, moved around the country 12 times. She kept the dress with her throughout their moves. She showed the dress to her two children and four grandchildren and took it with her when she talked about her experiences at junior high schools in Tokyo.

Learning of this, the Tokyo Federation of A-bomb Sufferers Organizations suggested that Ms. Takase donate the dress to the Peace Memorial Museum. She wondered whether she should give it up, but her daughter, Yuko Nishihara, 60, who lives next door, urged her to do so. In 2006 she visited Hiroshima again with her brother Akimoto, who lives in Chiba Prefecture.

Futaba stopped visiting schools to talk about her experiences after she was diagnosed with ovarian cancer in 2011 and stomach cancer in 2012. During an interview at her home, Ms. Takase said, “My mother, who loved to sew, was concerned about her children ’til the very end. I want the dress to tell of the horrors of the atomic bombing on behalf of my mother and me.” With a calm expression on her face, Ms. Takase described her hopes for the dress’s future.

(Originally published on April 14, 2015)

■Coins serve as mementoes

Thoughts of family as she polishes them

Sonoko Nishimura, 85, a resident of Higashi Hiroshima, held up five tarnished coins, two 1-sen coins, a 10-sen coin, a 50-sen coin and a copper coin, as she stood at the site of her former home next to the Funairi Honmachi stop on the Eba streetcar line in Hiroshima’s Naka Ward. “Unfortunately, this is all I have left to remember my parents by,” she said in a bright tone, though her eyes were wet with tears.

Her father, Ichiji Himaru, 56, and mother, Toshiko, 55, lived and worked at a dormitory for a technician training center of the Chugoku Branch of the Japan Electric and Transmission Company (now Chugoku Electric Co.) in Funairi Honmachi, providing meals for the dormitory’s 90 teenage residents. Fifteen-year-old Sonoko was the youngest of six children and the only one still living with her parents. She was employed at the field shipping workshop in Ujina-cho (now part of Minami Ward).

On the morning of August 6, 1945, Toshiko helped her daughter tie her canvas shoes and sent her off to work saying, “Be someone people can love.” That was the last time Sonoko saw her mother.

The two-story wooden dormitory building, which was about 1.6 km from the hypocenter, collapsed and burned. Sonoko was at the shipping workshop at the time of the atomic bombing. She fled to Kanawajima Island just offshore and spent a sleepless night among the injured who were brought there. The next day, accompanied by an official, she went by boat from Ujina Port to Eba-machi and looked for her parents, but she could learn nothing of their fate. Her eldest brother Ikuro, 35, who worked at the Kure Naval Arsenal, came to get her on August 9, and they then headed back to the site of the dormitory.

“A resident of the dorm who had survived and returned to the site bowed to us,” she said. The young man told them that Ichiji had been trapped in the building’s front entrance and had called for help, but the flames were approaching, and he could not pull Ichiji out. Sonoko and her brother dug at the spot and found Ichiji’s skeletal remains. Toshiko’s body was lying nearby.

The five coins were found near the air raid shelter that Ichiji, who was disabled, had dug next to the dormitory. Ichiji had kept the copper coin, of a type that had been made until the mid-19th Century, as a memento of his own mother.

After the war Ms. Nishimura relied on the help of relatives and worked in a textile mill in Miyoshi, Hiroshima Prefecture. She lived in a dormitory where she kept the coins in a sewing basket her brother had made for her. She sometimes took them out to polish them. She thought of them as a sort of amulet from her parents. After she married at the age of 22, she put the coins in the Buddhist altar of her new home. She took them out every August 6 and recalled her parents.

She donated the five coins to the museum in 2009 after the death of her husband. She lives next door to her son and his wife, and said she had begun to feel her age. She is the only one of the children in her family who is still living.

“When I hold these coins, I recall what I saw and felt when we gathered up my father’s remains,” Ms. Nishimura said. “I lost my parents to the atomic bombing and was left with almost nothing to remember them by. I would like future generations to know as much as possible about the A-bombing.” Including her parents, a total of 26 people were killed at the dormitory. Few people are left who know the facts of the atomic bombing, and her desire to convey the facts through the coins remains unchanged.

■Canteen travels to U.S.

Hope that tragedy is never repeated

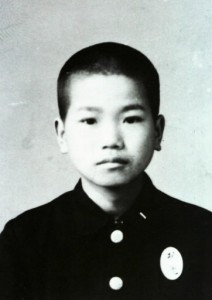

A bag containing the lunchbox and canteen of Shigeru Orimen, 13, a first-year-student at Hiroshima Second Middle School (now Kanon High School) was found by his mother along with his nearly unrecognizable body. His charred canteen has traveled to New York, where it will be displayed in an exhibition on the atomic bombing being put on by the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki starting April 27. The exhibition will move to Washington, D.C. in June.

On August 6 the first-year students of Hiroshima Second Middle School gathered on the bank of the Honkawa River, which runs alongside what is now Peace Memorial Park, and prepared to demolish buildings to make fire breaks. The site was about 500 meters from the spot at which the atomic bomb exploded. A total of 321 students were killed.

Shigeru’s mother Shigeko, who died in 1996 at the age of 88, came to the city from the village of Yahata (now part of Saeki Ward, Hiroshima) to look for him. Her husband had been drafted. On August 9 she found Shigeru’s face-down remains near the spot where the students had been working. With him was the bag containing his hand-me-down aluminum lunchbox, which bore the name of his elder brother Masaaki, and his canteen.

“When my mother looked at my brother’s belongings, she would weep and say, ‘Poor thing. He didn’t even get to eat his lunch,’” Shigeru’s younger brother Akio, 79, a resident of Saeki Ward, recalled. At the time of the atomic bombing, Akio was a fourth grader at a national school. He helped provide aid to victims who fled to Yahata. “My brother’s death, the miserable state of the injured – those things motivated me to become a doctor,” he said.

In 1967, Akio, who had become an inzternist, got involved in work for a health center run by what is now the Hiroshima Atomic Bomb Casualty Council in Naka Ward. He also served as secretary of the Hiroshima International Council for the Radiation-exposed, which was formed by Hiroshima Prefecture and others in 1991.

Akio spoke of the sadness the atomic bombing brought on his family and the frightful effects of radiation on the human body. “I’m sure my mother would have gladly sent my brother’s belongings to the U.S. if she believed they would convey those things to the people there,” he said. Shigeru’s mother donated his canteen and lunchbox to the Peace Memorial Museum in 1962. Akio believes it was her hope that the tragedy of the atomic bombing never be repeated.

■Young girl’s wooden clog

Substitute for remains; wiped it every morning

Miyoko Osugi, 13, was a first-year student at Hiroshima Municipal Girls’ High School (now Funairi High School) on the day of the atomic bombing. That day she left the family home in Minami-machi (now part of Minami Ward) wearing a pair of wooden clogs. Despite the passage of time, the outline of Miyoko’s foot and some writing in ink later added by her mother Tomiko, who died in 1971 at the age of 67, are still faintly visible on Miyoko’s left clog.

A total of 541 first- and second-year students from the school were in an area from the former Kobiki-cho to the bank of the Motoyasu River, south of what is now the Peace Memorial Museum, to work on the demolition of buildings to create fire breaks. All of them were killed in the A-bombing.

Tomiko and Miyoko’s brother Teruaki, an employee of the Hiroshima Railway Bureau, looked for Miyoko, but could not find her. Tomiko, however, walked the area where the students had been working and two months later found one of Miyoko’s clogs under a burned roof tile not far from the site. She recognized the clog from the thong, which she had made from one of her kimonos.

“Miyoko’s remains were never found, so my mother-in-law treasured the clog instead,” said Teruaki’s widow Nobuko, 80, a resident of Nishi Ward, recalling time she spent with Tomiko. Nobuko married Teruaki in 1960 and Tomiko lived with the couple. Teruaki died in 2011 at the age of 84. Tomiko carefully wiped the clog every morning and recited a sutra, Nobuko said. Tomiko talked about her recollections of Miyoko to Nobuko and lamented Miyoko’s death at such a young age.

Tomiko donated the clog to the museum in 1963. She hesitated to do so, saying she would miss it, but Teruaki persuaded her to donate it. “He told her everyone would be able to understand the family’s sadness,” Nobuko said.

A publication called “Floating Lanterns” was compiled by parents of students from the Hiroshima Municipal Girls’ High School in their memory. For Volume 4, which was published in 1996, Teruaki wrote: “If I had taken your place, oh, baby sister.” These sentiments are shared by his 52-year-old son who lives in Hagi, Yamaguchi Prefecture. Now, in the summer, accompanied by two grandchildren, Nobuko says a silent prayer at the family grave where Miyoko also rests and the monument to the students of Hiroshima Municipal Girls’ High School along the bank of the Motoyasu River.

“I’m sure my mother-in-law and husband will rest in peace if people think of the senselessness of war when they see the wooden clog,” Nobuko said. The clog, which had great significance for the family, is on display in the Peace Memorial Museum. The museum attracts 1.38 million visitors annually.

■Dress made by mother

Kind mother; dress carries hopes

When she and her mother fled after the atomic bombing, Futaba Takase, 87, now a resident of Tokyo, was wearing a dress her mother had made for her. Amid the shortage of supplies during the war, her mother had been able to get hold of some meisen silk cloth, from which she made the dress.

On the day of the atomic bombing, Futaba was with her mother, Setsuko Mito, 38, and her 15-year-old sister at the home of a relative in Ote-machi. Her father, who worked for the Ministry of Transportation and Communications, had died, and Futaba had moved with her family to her parents’ hometown of Hiroshima on July 26 to escape air raids in Tokyo.

Their home was approximately 1.2 km from the hypocenter. Futaba, her mother and sister were trapped under the house when it collapsed. “My mother had a piece of wood stuck in her leg. She pulled it out herself, and then removed the wood that was on top of me,” Ms. Takase said. But her mother was seriously injured. The two girls supported their mother, one on each side, and the three of them fled to Kanawajima Island. From there they were taken to Kuba National School (in what is now the city of Otake) on a military ship and temporarily housed there.

Setsuko was by then only half conscious, and she died on September 1. Futaba was still wearing the dress her mother had made for her. Setsuko’s last words were: “I want to see my son, but it’s too late.” Her son, Akimoto, 11, had already entered the elementary school affiliated with the Hiroshima Higher Normal School and had been evacuated to the northern part of the prefecture with other children. He did not return until September 3. At the end of October, Futaba set off for the home of her aunt in Okayama with little more than the clothes on her back. Her face was swollen, and she was suffering from diarrhea.

Five years after the atomic bombing, she married. She and her husband, an employee of the Bank of Japan, moved around the country 12 times. She kept the dress with her throughout their moves. She showed the dress to her two children and four grandchildren and took it with her when she talked about her experiences at junior high schools in Tokyo.

Learning of this, the Tokyo Federation of A-bomb Sufferers Organizations suggested that Ms. Takase donate the dress to the Peace Memorial Museum. She wondered whether she should give it up, but her daughter, Yuko Nishihara, 60, who lives next door, urged her to do so. In 2006 she visited Hiroshima again with her brother Akimoto, who lives in Chiba Prefecture.

Futaba stopped visiting schools to talk about her experiences after she was diagnosed with ovarian cancer in 2011 and stomach cancer in 2012. During an interview at her home, Ms. Takase said, “My mother, who loved to sew, was concerned about her children ’til the very end. I want the dress to tell of the horrors of the atomic bombing on behalf of my mother and me.” With a calm expression on her face, Ms. Takase described her hopes for the dress’s future.

(Originally published on April 14, 2015)