Hiroshima: 70 Years After the A-bombing: Paper Monuments 10

Apr. 14, 2015

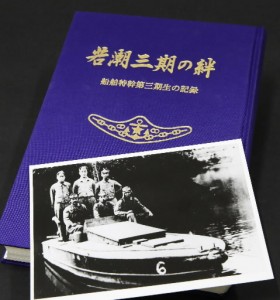

Bonds Between Trainees of the Young Tide, book of reflections by soldiers in suicide attack unit, published in 1995

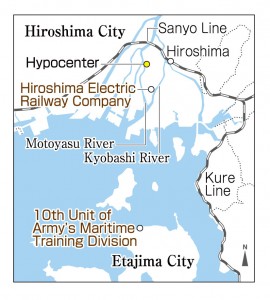

During World War II, a military unit comprised of teenagers, the 10th educational unit of the Army’s Marine Training Division, was based in Konoura at the northern end of Etajima Island in the Seto Inland Sea. According to Record of the A-bomb Disaster, “The naming of this unit was a camouflage for its true function. In reality, it was the Army’s special water attack unit.” Trainees were recruited from across Japan as special officer candidates for the Army’s marine forces and underwent training to perform suicide attacks in preparation for the anticipated assault by the enemy on the Japanese mainland.

Rescue operations ordered after A-bombing

The atomic bombing of August 6, 1945 completely decimated the defense and administrative functions in the city of Hiroshima. Amid these conditions, the 10th educational unit was ordered to immediately engage in rescue operations. As Record of the A-bomb Disaster notes, the unit was best equipped to perform this role because it was an organized entity, with trained soldiers and a fleet of small boats. Bigger boats could not enter the rivers of the delta, while trucks were blocked by the wreckage of buildings heaped on the roads.

Isao Wada, 88, a former trainee of the unit and a resident of Higashi-sendamachi in Naka Ward, arrived at Ujina Port (now Hiroshima Port) at around 3 p.m. that day, along with 30 to 40 other members of the unit. He recounted his experience in the book Wakashio Sanki no Kizuna (Bonds Between Trainees of the Young Tide), which he compiled and issued. The book is a collection of accounts written by the third group of trainees, who had entered the unit in February 1945. It was published in 1995, 50 years after the war ended.

“When I took my first step toward the city center, I was stunned, like my hair was standing on end,” Mr. Wada wrote in his account. “This is the real war, I thought. It was just so cruel, so sad.”

The unit’s base for rescue operations was made at the head office of the Hiroshima Electric Railway Company, in today’s Naka Ward. Mr. Wada and his fellow soldiers put the injured on their backs and carried them with a makeshift stretcher made of poles and a straw mat. When people were dying, and wanted water, Mr. Wada gave them some and prayed that they would rest in peace.

At night, the unit camped on the grounds of the Hiroshima Technical Institute, now part of the Hiroshima Prefectural Library in Naka Ward. On August 7, they removed bodies near Hijiyama Bridge, which spanned the Kyobashi River, and did the same grim task at the Motoyasu River, beneath the A-bomb Dome, on August 8. The skin of the dead became wrinkled after soaking in water and easily peeled off when the bodies were pulled. To cremate the corpses, they gathered wood from the trees that remained, doused the pile with heavy oil, and set it ablaze. To mark graves, they used pieces of wood or stones.

From August 10, the members of the unit walked around Otemachi, near the hypocenter, to remove and cremate the bodies of those who had been buried under fallen buildings. They found bodies whose gender could not be identified as well as parts of bodies left behind after the blaze. A world “beyond all imagination” spread out before their eyes.

Feeling both emptiness and joy

Mr. Wada returned to their base in Konoura on August 12. After the emperor’s broadcast on August 15, announcing Japan’s surrender, he was ordered to destroy the unit’s plywood suicide crafts with explosives. He felt a mix of emptiness and joy because “Although I was supposed to die for my country, I had survived and could now return to my family instead.”

After the war, he went back to his previous work at the Hiroshima Railway Bureau (today’s West Japan Railway Company), but then switched careers and became a barber. Dreaming of an independent life, he opened his own barber shop at its current location in 1953, after a period of apprenticeship, and worked diligently with his wife.

In 1967, the “Cenotaph for the War Dead” for the army’s marine suicide attack units was raised at the Konoura coast to commemorate the 1,636 soldiers who died in sea operations, such as suicide attacks in Okinawa. Taking this opportunity, Mr. Wada traced the whereabouts of his peers who had entered the unit in the same year.

Among the 2,160 members of the third group of trainees, about 1,260 were exposed to the A-bomb’s radiation. Seven men, who had been transferred to the marine communications squadron in the city, were killed in the blast. Also, not knowing the horrors of radiation, at least 10 trainees of the third group stayed in Hiroshima and died from “a disease of unknown cause” after they were demobilized.

It took Mr. Wada four years to compile his book, which consists of 141 writings. Fifty-one offer unvarnished accounts of personal experiences of the atomic bombing, including scenes witnessed during the rescue operations. “Having devoted their lives to their country, these young men wrote about the things they saw and felt,” Mr. Wada said. “This is a record of youth during wartime, as well as the emptiness of war.”

Today, the Japanese government is promoting legislation for a new security framework which would dramatically alter the direction this nation has taken since the end of World War II. Most of the present population have no experience of war. Mr. Wada stressed, “It’s vital that we protect the peace of our country by not engaging in warfare with other nations.” Though there are fewer former trainees still in good health, they will come together in Hiroshima in September and visit Konoura.

(Originally published on April 6, 2015)