Hiroshima: 70 Years After the A-bombing: Operation orders issued in the aftermath

Feb. 19, 2015

Rescue operations undertaken without knowledge of A-bomb

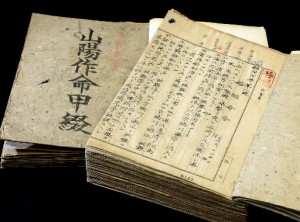

There is a collection of exceptional historical materials which clearly convey the efforts that were made to rescue victims in Hiroshima in the devastating aftermath of the atomic bombing. A total of 50 written operation orders issued by the Imperial Japanese Army’s Shipping Command, which was located in Ujina-machi (today’s Ujina Kaigan in Minami Ward), are preserved in a file at the National Institute for Defense Studies. These orders were issued between 8:50 a.m. on August 6, 1945, and noon on August 9. The last order was numbered 53, while orders 34, 35, and 36 are missing. This article explores the significance of the atomic bombing to people today, and to future generations, by examining the operation orders from that time, along with the memoir written by the former commander who issued the orders and the testimonies of others. The operation orders are all marked “Confidential” at the top. Order No. 1, which was issued at 8:50 a.m., 35 minutes after the A-bomb blast, begins with the following remarks:

“1. After a bombing by enemy aircraft at 8:15 a.m. today, August 6, fires have broken out in many areas. Coupled with the blast, there appears to be extensive damage.”

“2. I intend to contribute to firefighting and rescue operations in Hiroshima.”

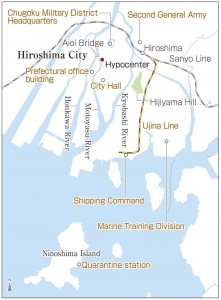

This is a chronological record of orders dictated by Commander Bunro Saeki, then 55. The headquarters of the Army’s Shipping Command was a building located in Ujina, 4.6 kilometers from the hypocenter, and its units were stationed in the coastal areas of Niho-machi and Ninoshima Island, thus escaping serious damage.

“3. Captain of the maritime guard unit is ordered to send firefighting vessels to areas along the Kyobashi River to perform firefighting duties.”

“4. Captain of the Hiroshima shipping unit should use some of their boats to transport victims to Ninoshima Island, and…”

Into the raging flames

With no idea that the bomb was an atomic bomb, the soldiers of each unit went into the central part of Hiroshima, which was still enveloped in flames, to extinguish the fires and bring the injured to an army quarantine station on Ninoshima Island.

Their emergency operations began while they were still unable to contact the Second General Army (located in present-day Higashi Ward), which was in charge of the troops in western Japan, or the Chugoku District Military Headquarters, located in the city center. The prefectural government office, city hall, and medical institutions all suffered catastrophic damage.

Masao Maruyama, then 31, was a first-class private and belonged to the intelligence section. He was listening to instructions from a senior officer in front of the Shipping Command building when he saw the bomb’s flash. Mr. Maruyama later became Japan’s leading historian of political philosophy. Twenty-four years later, he described his experience to the Chugoku Shimbun. The interview was recorded on tape, and still exists.

Mr. Maruyama said that, about 15 minutes later, the injured “began arriving on the premises in small groups, in a state of shock. There was open space as far as the coast, but that space filled up with people.”

Other pages of the operation order file indicate that firefighting operations started on the north side of Hijiyama Hill at noon. The flames had been spreading in the area. For the firefighting and rescue operations along the Motoyasu River, which runs near the hypocenter, the 10th training unit of the Marine Training Division was sent from their base at Konoura in Etajima (part of today’s Etajima City). This unit, designed to train soldiers for special missions, was composed of teenagers.

Denkichi Yamamoto, 85, a resident of Saeki Ward, was a member of the training unit. He said, “We went into Hiroshima in groups of 20 to 30 in the afternoon. Our group went as far as a command post located at the head office of the Hiroshima Electric Railway Company, but we couldn’t go any further because the area beyond that was a sea of flame.”

Following these units, everyone at headquarters “except those belonging to the telegram section were ordered to suspend regular operations to undertake rescue operations.” By 2 p.m., “8,300 civilians, dead and injured, were admitted to aid stations.”

At 4:50 p.m., the decision was made to hand out clothing to 10,000 people. About 9,600 hard biscuits, 6,500 work clothes, and 7,000 jars of tangerines were given to city officials for distribution to the injured.

The units also searched for Prince Lee Woo, then 32, a member of the imperial family of Korea, which was under Japan’s colonial rule. As a member of the education staff of the Second General Army, he was stationed in Hiroshima at the time.

At 4 p.m., it was reported that the prince had gone missing on his way to work, and a search was immediately begun. He was found at a lower reach of the river near Aioi Bridge, close to the hypocenter, and taken to Ninoshima Island, where most of the medical officers were caring for the injured. The prince died shortly after 3 a.m. on August 7. On August 8, the Imperial Household Ministry and the Army Ministry announced that he was killed in an air strike.

At 6 p.m., not only the medical staff but also 100 female secretaries were sent to the island to strengthen relief operations. But the aid station was filled to capacity by 8:40 p.m., and 1,000 people were transferred to four aid stations on the mainland in motorboats and tugboats.

By 9:30 p.m., the flames that burned most of the Hiroshima delta had finally died down. But one of the orders noted: “Fires around the Motoyasu and Ota rivers, presumedly around the prefectural government office, have been gradually growing stronger.”

Bodies disposed of on site

The following morning, more details of the damage became clear. Order No. 32, issued at 7 a.m. on August 7, stated:

“Many more injured people in Hiroshima have not been admitted to aid stations.” So the order was made to “suspend treatment of admitted patients and focus on giving first aid on the front lines.” There was no choice but to take emergency measures, providing basic treatment to the living and disposing of the dead then and there.

According to a report which provides an overview of the measures pursued in the aftermath of the bombing, which is preserved at the Hiroshima Municipal Archives, military brass and Hiroshima Governor Genshin Takano, then 50, held a meeting at 10 a.m. on August 7. The governor had rushed back from a business trip to the eastern part of Hiroshima Prefecture on the evening of August 6. They decided that the difficulty of transporting the bodies of victims meant that “they should be cremated or buried on the spot.” Priests from outlying areas, both Shinto and Buddhist, were called to recite sutras for the dead.

The Shipping Command dispatched some of its personnel around 10:20 a.m. to work on restoring water and electricity. This was part of efforts to overcome the damage and continue fighting the war.

On August 7, Commander Saeki, who took charge of Hiroshima’s security, made leaflets to inform the public of the 18 aid stations and accept inquiries about food, water, and medicine. Citizens were called upon to “Inspire enthusiasm to wipe out the American devils and support recovery efforts from the war damage.”

The series of operation orders ends with No. 53, issued at noon on August 9, which made the order to take about 200 injured people admitted to the military platform at Ujina Station to Ninoshima. But it is highly likely that more orders were issued after that.

Ten years after the war, Commander Saeki wrote a memoir of the time, which he titled “An Outline of Hiroshima’s Handling of the War Damage.” He indicated that the number of bodies recovered by August 13 totaled about 28,000, and the number of injured was 13,000. On the day before the Imperial Rescript of Surrender was released, he was called back to Tokyo, and the recovery efforts were then entrusted to the Chugoku Military District Headquarters.

Some of his writing appears in Volume 1 of the Record of the Hiroshima Atomic Bombing, published by the city government in 1971.

The special orders were among the 503 items gathered by officers in charge of collecting historical materials at the former Health and Welfare Ministry’s returnee support bureau, then transferred to the National Institute for Defense Studies in 1964. But the existence of these orders was unknown. Fukuhei Ando, 66, former vice director of the Hiroshima Prefectural Archives, located them.

Mr. Ando said, “The operation orders are official documents which confirm the accuracy of the commander’s memoir. They convey how the rescue operations were launched in Hiroshima. Soldiers dispatched for rescue operations under those orders were also exposed to radiation.” More than 4,000 members of the shipping command were dispatched from inside and outside the city of Hiroshima, including from the cities of Mihara and Tadanoumi (now Takehara).

Call for a ban on atomic weapons

According to a book which provides a comprehensive view of the history and major figures of the Imperial Japanese Army and Navy, Mr. Saeki was originally from Miyagi Prefecture in northern Japan. He became a shipping and transportation commander in 1940, and lieutenant general the following year. (The Shipping Command was established in 1942.) He died in his hometown in 1967, aged 77. When his 89-year-old daughter was interviewed at her home, she was reticent when it came to her father. “My father did not talk much about what happened in Hiroshima after he returned here,” she said. Her mother and sister experienced the atomic bombing in Furuta-machi (present-day Nishi Ward), where the family lived.

Mr. Saeki’s memoir includes a chapter titled “Reminiscences,” which does not appear in the city’s record of the atomic bombing. In this chapter he refers to the Bikini Incident, where crew members of the Daigo Fukuryu Maru (The Lucky Dragon 5), a Japanese fishing boat, were exposed to radioactive fallout from a U.S. hydrogen bomb test. He gives his frank views on atomic and hydrogen bombs.

“Since we did not have knowledge of the bomb or atomic diseases at that time, the rescue operations could not produce adequate results, which is extremely regrettable,” he wrote. He added that the government should pursue research on exposure to radiation and take measures to improve the public’s understanding of these issues.

“The use of atomic weapons must be banned,” he also wrote. “We must convey this to people all over the world, again and again, so that a ban will be made.”

Once a nuclear weapon is used, the damage cannot be undone. This was the conclusion he came to, after witnessing the destruction of Hiroshima firsthand.

(Originally published on February 10, 2015)