Hiroshima: 70 Years After the A-bombing: Paper Monuments 2

Feb. 3, 2015

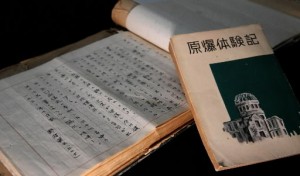

Accounts of the A-bombing, with deletions, published in 1950

Through A-bomb accounts, or “paper monuments,” this series explores the significance of Hiroshima 70 years after the atomic bombing.

Five years after the atomic bombing, the City of Hiroshima pursued a campaign to collect survivors’ accounts of the atomic bombing. Among the 165 accounts that were submitted, 18 were chosen for a book titled Genbaku Taikenki (Experiences of the Atomic Bombing), which was published on August 6, 1950.

Among these 165 accounts, 84 survivors were in primary or secondary school at the time of the bombing, while 81 were adults, including university students. They were exposed to the atomic bomb at various locations. All of these accounts, preserved at the Hiroshima Municipal Archives, provide a vivid picture of what happened that day. Comparing the published book with the original manuscripts reveals the difficulties Hiroshima faced back then when it came to publishing what people actually wrote about their experiences and their thoughts.

The only survivor of 37 employees

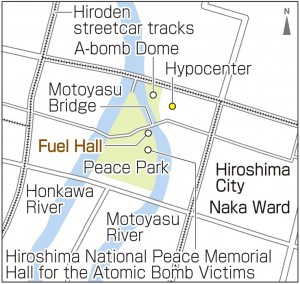

The book begins with the account written by Eiso Nomura, who miraculously survived the atomic bombing at a location about 170 meters from the hypocenter. The title of his account, as it appears in the book, is “Exposed at the Hypocenter.” He was in the basement of the Fuel Hall, today’s Rest House in Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park. He was 47 years old.

“Oh! Someone is here! I tried to hold her up and speak to her. I did what I could, but her head was slumped down. It seemed she was already dead.” Calling for help, Mr. Nomura ran from the building, seeking to flee the approaching fire. He became the only survivor of the 37 people who were working that day at the Hiroshima Prefecture Fuel Rationing Union.

His account ends with the words: “The spirits of those 36 people, rest in peace! Alas!”

Mr. Nomura escaped direct exposure to the bomb because he was in the basement at that moment, protected by thick concrete walls. He still suffered from acute radiation symptoms, but somehow recovered. In the spring of 1946, he returned to Hiroshima with his wife and four children and lived in a makeshift hut.

Hideo Nomura, 80, who lives in Naka Ward, Hiroshima, is Mr. Nomura’s third son. Recalling those days, he said, “Every day was a struggle to go on, but my father probably felt it was his duty to write about his experience when he heard that the city was collecting A-bomb accounts.” His father was in poor health, but he supported the family by selling Japanese clogs and tea.

In May 1950, the City of Hiroshima announced that it had created the collection of A-bomb accounts. The survivors wrote in straightforward prose about their vivid memories and intense emotions at the time of the bombing.

A former mobilized student, who lost many friends working to demolish houses to make fire lanes in the city, wrote, “I don’t think I was the only one who felt pent-up rage.” A teacher who lost his wife and children wrote, “I doubt the humanity of the United States, which dared to carry out such an atrocity…I will strive to eradicate such tremendous suffering from this earth forever.” These accounts, however, were not adopted for the book.

The accounts chosen for the book were checked as well, and any sentences not considered appropriate were deleted.

Futaba Kitayama, who was 33 years old at the time of the bombing, lost her husband and suffered burns to her face but sought to go on living for her two sons and daughter.

She wrote, “In these critical international conditions, I hope that the atomic bombing did not steal away the precious lives of 200,000 people for nothing, but that they died for peace. I hope this will be shown to the world.”

The Civil Censorship Detachment (CCD), established by the General Headquarters of the Allied Forces (GHQ), was closed in October 1949, but the Korean War broke out on June 25, 1950, when the United States and the Soviet Union faced off in Asia.

The Peace Festival (today’s Peace Memorial Ceremony) was canceled by the civil affairs bureau for the Chugoku Region (in the city of Kure), which oversaw the administration of the occupation in Hiroshima. Initially, “about 1,500 copies of the book were to be printed and distributed to the Diet and all prefectural and city governments in Japan.” (The Chugoku Shimbun, August 8, 1950) However, the book was distributed only to those involved in the project.

Twenty years after the atomic bombing, the buried book of survivors’ accounts found new life. The Asahi Shimbun added 11 more accounts and published the book under the same title, Genbaku Taikenki, in 1965. The book is now published by Asahi Sensho and has been reprinted many times.

Hoping all the accounts will be read

The original handwritten manuscripts are now hard to read because of the deterioration of the paper. Hiromi Hasai, 83, professor emeritus of Hiroshima University, made digital files of all the manuscripts and gave the data to the City of Hiroshima in 2011. Professor Hasai, who has also been engaged in various activities as a survivor of the atomic bombing, said, “These accounts weren’t influenced by the knowledge that was acquired later or by the trend of the times. People wrote outspokenly that they could not forgive the atomic bombing. These accounts should be read widely.”

Copies of all 165 manuscripts are held at the Hiroshima National Peace Memorial Hall for the Atomic Bomb Victims, where they can be read by the public, but Professor Hasai wants them to be read more widely. He produced the digital files in the hope that these accounts of the atomic bombing will be made available online.

(Originally published on January 19, 2015)