Hiroshima: 70 Years After the A-bombing: Paper Monuments 1

Jan. 28, 2015

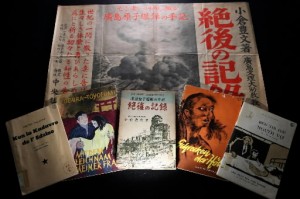

Letters from the End of the World: A Firsthand Account of the Bombing of Hiroshima, published in 1948

Through A-bomb accounts, or “paper monuments,” this series explores the significance of Hiroshima 70 years after the atomic bombing.

In the opening passage of Letters from the End of the World: A Firsthand Account of the Bombing of Hiroshima, Toyofumi Ogura shares the words his dying wife Fumiyo uttered in broken bits. He had found his 37-year-old wife at a temporary relief station at Fuchu National School, located on the outskirts of the city. It was the evening of August 7, 1945, one day after the atomic bombing of Hiroshima.

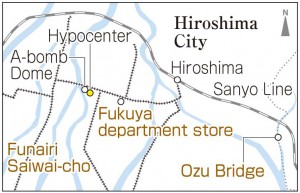

“That was a huge bolt of lightning!” she thought, from in front of Fukuya department store. Then she blacked out.

Mr. Ogura’s book, one of the earliest publications about the atomic bombing, is written in the form of letters to his late wife.

On August 6, when Mr. Ogura came to the east side of Ozu Bridge, which spans the Fuchu Okawa River, he saw a flash of light. He was 45 and an associate professor of Japanese history at Hiroshima University of Literature and Science (now Hiroshima University). He lived in Funairi Saiwai-cho (now part of Naka Ward) with his wife and second son. His first son and daughter were students at the national school affiliated with Hiroshima Higher Normal School, and were staying at a temple in Saijo (now part of Shobara) in the northern part of the prefecture in the event of air raids on the city.

Vivid description of devastation

Letters from the End of the World vividly describes what Mr. Ogura witnessed while searching for his wife and child in a city where human beings had become the living dead. He managed to bring his wife to a relative’s house in Jigozen (now part of Hatsukaichi, Hiroshima Prefecture), but she died there. He calmly recounts the last moments with his wife.

Fumiyo encountered the flash of the atomic bomb while in front of Fukuya department store, about 710 meters from the hypocenter. She spoke deliriously about the children’s meals and snacks before dying on August 19.

During her wake, Mr. Ogura and his children chanted in chorus Standing Up to the Rain by Kenji Miyazawa, a writer he had ardently admired since childhood. Mr. Ogura wrote, as if speaking to his wife, that all five members of the family slept side by side as they always did, and that he held his wife’s cold, stiff body in his arms until dawn.

Recalling that time, Keiichi Ogura, 78, Mr. Ogura’s eldest son and a resident of Chiba, said, “My uncle brought my sister and me back to Hiroshima on August 18.”

Back then, his sister Kazuko was 11 and his brother Kinji was 7. Kinji, who died in 2002, experienced the bombing near their home. The three siblings, born two years apart, moved to present-day Wake, Okayama Prefecture in the spring of 1946. There they were cared for by a woman who was once their father’s student. When they visited their father at his lodging house, he was invariably writing, using a tangerine crate as a desk.

At the request of a publisher in Tokyo, he was preparing the letters he wrote to his late wife for publication. He also gathered as much information as possible on the extent of the A-bomb damage and the “lingering fears” of radiation sickness. The title was taken from words found in the book, which was published in November 1948.

Perhaps to slip the book through censorship imposed by the General Headquarters (GHQ) of the Allied Forces, the preface of the first edition quotes U.S. President Harry S. Truman saying that the atomic bombs were used to save the Japanese people from total destruction.

Letters from the End of the World, which is also a reportage of the horrific devastation of the bombing, was well received and six editions were printed by March 1949. As a large number of Japanese emigrated from Hiroshima Prefecture, the book was also popular abroad, and one edition was published to commemorate the export of the book. From Hawaii, 160,000 yen from the proceeds of sales of the book was donated to help children in Hiroshima.

An abridged edition of the book, Tsuma no Shikabane o Daite (Holding my Wife’s Dead Body), appeared in King magazine’s August 1950 issue, translated and published in East and West Germany, and serialized in newspapers in Bulgaria and Hungary. “Dad used to say that the atomic bombing should not be commercialized and he donated all royalties from the book. He was always away from Hiroshima on August 6 because he felt restless.”

Following late father’s antinuclear stance The English translation of the book, sought by the family, was made for the abridged version in 1994 and for the full version in 1997, one year after the author’s death at the age of 96. His body was donated to the school of medicine at Chiba University, where Keiichi had studied. Toyofumi’s children chanted Standing Up to the Rain in chorus at his funeral.

Keiichi was involved in public hygiene in Chiba Prefecture, where his father was from originally. “Why did my mother have to die? This is the reason I chose work that helps protect people’s lives,” Keiichi said. He buys copies of Letters from the End of the World and gives them to others. He writes on the front: “With compliments, following my father’s antinuclear stance, Keiichi Ogura.”

(Originally published on January 12, 2015)