Hiroshima: 70 Years After the A-bombing: 12-year-old “war dead” 1

Jul. 9, 2014

Sister’s uniform and diary

One singular aspect of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima is the large number of mobilized students who were killed. The deaths of 7,196 students from 48 schools, mostly junior high schools and girls’ schools, have been confirmed. Most of them were engaged in the demolition of buildings in the Hiroshima delta area on the morning of August 6, 1945. By order of the government, students had been mobilized to create large firebreaks in anticipation of air raids by the United States military. Under the provisions of the 1952 Act on Relief of War Victims and Survivors, mobilized students were classified as “paramilitary” and recognized as “war dead.” These articles look at the lives and deaths of mobilized students whose futures were stolen based on their siblings’ accounts of their A-bombing experiences.

Final diary entry on August 5: “Do a good deed every day”

On August 5, Mutsuko Ishizaki, 12, a first-year student at First Hiroshima Prefectural Girls’ High School (now Minami High School), wrote in her diary as usual, noting that the skies were clear that Sunday. She reported that in the morning she helped a classmate who had transferred to the school with her studies and in the afternoon she went swimming in the river. She closed by saying, “Today was a very good day. I want to continue to do a good deed every day.”

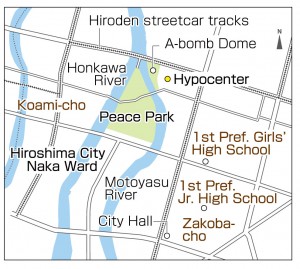

Mutsuko’s sister, Hiroshima resident Noriko Ueda, 82, then a second-year student at the same school, recalled the morning of August 6. “Mutsuko got money from our mother to buy a straw hat to wear when she worked,” Ms. Ueda said. “I think she was happy about that.” The two girls left their home in Funairi Kawaguchi-cho (now part of Naka Ward) together. Mutsuko headed for Koami-cho (Naka Ward) to work on the demolition of buildings throughout the neighborhood, while Noriko set off for the Hiroshima Printing Company in Minami Kanon-machi (Nishi Ward), where she had been working for some time. They parted unconcernedly, Noriko said.

After the A-bombing, Noriko and some classmates headed for the hills of Koi-cho (Nishi Ward). The next day Noriko met up with her parents and youngest sister at the farmhouse they had agreed to flee to, but Mutsuko never appeared.

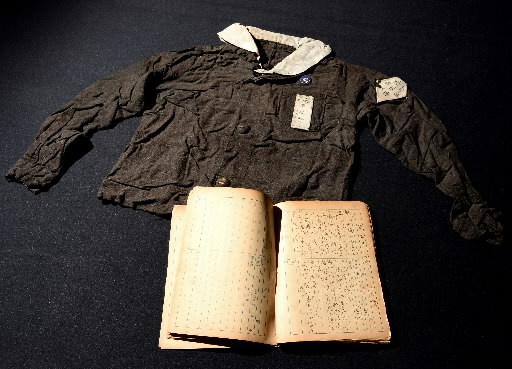

Their father Shuichi, 42, walked the city in search of Mutsuko and after about two weeks returned with the jacket of her uniform, which was found under rubble at her worksite. Apparently, before setting to work Mutsuko had removed the jacket, which had been made from cloth used for one of her father’s kimonos, folded it and concealed it somewhere. The name tag sewed onto the front bearing her name, blood type and the name of her school escaped the fire along with the name of her school and group on the sleeve. A total of 223 first-year students working at that site were killed.

Mutsuko’s mother Yasuyo, 37, dissolved in tears upon seeing the uniform. After that, she slept clutching it to her. She saved Mutsuko’s diary, though she never told her other children about it. Noriko first saw the diary at the time of the Buddhist memorial service marking the 33rd anniversary of Mutsuko’s death. Noriko graduated from junior college, married and had a son. She was anguished by her mother’s sorrow and grief.

Mutsuko began keeping the diary on April 6, the day she entered the prefectural girls’ high school. That day she wrote, “I was inspired to study as hard as I can.” But classes were frequently interrupted by air raid warnings. Starting on May 7, classes were held in morning and afternoon shifts. In order to increase the production of food, students continued the work of clearing land at the Yoshijima Air Field (Naka Ward) and the East Drill Ground (Higashi Ward).

In her diary Mutsuko admonished herself to carry on “for the sake of the soldiers” even when she was tired and said Japan “must defeat America and England no matter what.” Meanwhile, she enjoyed chatting with her classmates and her family. Mutsuko’s diary reveals the commendable way in which she passed her days during the war.

Ms. Ueda described her feelings while working as a mobilized student: “I’d grown up hearing stories glorifying Japan’s victories in the Sino-Japanese and Russo-Japan wars at school, so I was determined to help my country.”

The war situation deteriorated, and in February 1944 the cabinet approved the “Outline of Emergency Measures for the Decisive Battle.” The mobilization of junior high and high school students to work in factories was expanded, but Ms. Ueda was not unhappy about it. On the contrary, she said, “It was unthinkable that Japan would lose the war.”

For more than 20 years Ms. Ueda has been recounting her A-bombing experiences and the story of her sister’s death to students on school field trips. She was urged to do so by Tamotsu Eguchi, a junior high school teacher in Tokyo who began promoting school trips to Hiroshima in the late 1970s. He was at Nagasaki Prefectural Keiho Middle School when the atomic bomb was dropped on that city. In his later years he moved to Hiroshima and was active in the effort to tell students about the A-bombing. Mr. Eguchi died in 1998 at the age of 69.

Noriko intends to continue recounting her experiences of the war and the A-bombing as a student as long as she is able to do so. “War leaves no citizen untouched. Children are not spared either,” she said. “I want people to know how dreadful war is. Even amid those circumstances, the students embraced life.”

(Originally published on April 7, 2014)