Hiroshima: 70 Years After the A-bombing: Depicting the A-bombing 7

Nov. 18, 2014

Homes at hypocenter: Two girls supported each other

Two girls sit on a riverbank, covering their faces. Badly burned people can be seen nearby. The wooden bridge spanning the river has partially collapsed. Beyond lies devastation in this depiction of the Nakajima district, an area in Hiroshima’s Naka Ward that became the site of Peace Memorial Park. The date is August 8, 1945.

“I wonder what would have become of me without your encouragement,” said Yasuko Onishi, 83, a resident of Kochi Prefecture. Tears came to her eyes as she stood beside the Motoyasu River, the river depicted in the picture.

“The most important thing is that we’re both healthy,” said Hiroshima resident Hisayo Ugawa, 83, gently putting her hand on her former classmate’s shoulder. Sixty-nine years ago the two women were together at this spot.

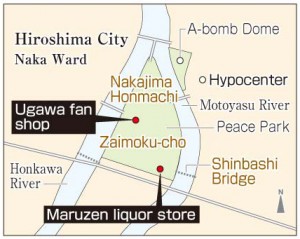

Both born and raised in the Nakajima district, the girls in the picture were second-year students at Hiroshima Jogakuin High School at the time of the A-bombing. Ms. Onishi’s home in Zaimoku-cho was the site of the family liquor store called Maruzen. At Ms. Ugawa’s home in Nakajima Honmachi her father ran a shop that sold fans. Both of the girls had been mobilized to work at the Army’s Second General Headquarters, located in what is now Futaba no Sato in Higashi Ward.

On August 6, 1945, the two girls were in a temporary wooden structure at the army headquarters that housed the cryptography team. They were trapped under the building when it collapsed. By the morning of August 8 the fires that had engulfed the city center had died down, and the girls were given permission to enter the city. They set out for Nakajima.

As they described the events of that day the women often met each other’s gazes. “Neither of us said a word as we stood beside the river, where dead bodies were floating.” “We embraced when we got back to army headquarters.”

Ms. Onishi lost her father Zenshiro Uneda, 50, mother Masako, 42, and younger sisters Keiko, 7, and Motoko, 5, in the A-bombing. Ms. Ugawa lost her father Kenzo Maruko, 54, and her elder sister Yoshie, 21, who worked at the Hiroshima branch of the Bank of Japan.

Encouraged by dog figurine

Ms. Onishi was left all alone, so Ms. Ugawa gave her classmate, who had often said she wanted a dog, a small dog figurine. Ms. Onishi moved around, staying with relatives of Ms. Ugawa and at the home to which a neighborhood acquaintance had evacuated. “I wandered aimlessly like a sleepwalker,” she said. “If it hadn’t been for the help of all those people, I would have starved to death.”

Ms. Onishi was eventually reunited with her elder brother, who had returned home after being discharged from the military, and in October she moved to Hyogo Prefecture, where an uncle lived. After that she entered a nursing school and worked at a hospital in the city of Himeji. In 1958 she married a dentist she met there. They moved to his hometown of Tosashimizu in Kochi Prefecture, where he opened a private practice. She raised two boys and a girl while running the clinic’s office.

Ms. Onishi said she never spoke about the atomic bombing to her family. She saved the thongs from the wooden clogs she was wearing that day but was teased for doing so by other residents of the nursing school boarding house. Though the pink thongs were a reminder of her mother, who had made them for her the day before the A-bombing, she burned them.

“Perhaps because I’m what is called a ‘bittare’ [coward] in Tosa dialect, I never had the courage to come to grips with my experience,” she said. Nevertheless she missed her hometown of Hiroshima, and in 1986 she paid a visit to Ms. Ugawa.

In 2002 Ms. Onishi learned of the call for art depicting the A-bombing. Her first grandchild had grown up, and she gradually came to believe that she had survived for a reason. She painted two watercolor pictures, one depicting the devastation that was etched in her mind and the other of the grounds of Seigan Temple in Zaimoku-cho. Street vendors had stalls just outside the temple gate, and she played there as a child. Her pictures were displayed at the Peace Memorial Museum the following year. Ms. Ugawa was contacted about the exhibition and went to see it.

“I knew right away it was the two of us. Thank you,” Ms. Ugawa said to her former classmate of the picture when they met for the first time in 28 years.

“Thank you,” said Ms. Onishi, pulling the dog figurine from her bag and repeatedly expressing her gratitude.

Passing memories on to future generations

With regard to the A-bombing artwork done by citizens, Ms. Onishi said, “It doesn’t fully convey the horror of the A-bombing. My picture too is based on my memories, so it’s not accurate like a photograph.” She added: “If memories aren’t preserved, they will vanish. Drawing a picture is a way to honor the dead so they will not be forgotten. And perhaps art conveys something that photos cannot, something that future generations will also sense.”

A total of 4,504 works of art depicting people’s recollections of the atomic bombing can now be viewed on the website of the Peace Memorial Museum, enabling people to learn about the impact of nuclear weapons.

This is the final article in the “Depicting the A-bombing” series.

(Originally published on October 20, 2014)