Hiroshima: 70 Years After the A-bombing: Donated Items 1

Aug. 29, 2014

The first nuclear attack in human history, when the United States dropped an atomic bomb on the city of Hiroshima on August 6, 1945, stole the lives of many and forced the survivors to endure tremendous hardship. Based on these experiences, the survivors have spent their lives, right up to the present, sharing their messages of warning and their hopes for peace. However, as they age and pass away, their memories of the atomic bombing are fading.

In response to a call from the Chugoku Shimbun, asking for artifacts that can convey the tragedy of the bombing to future generations, people have shared a variety of items, including mementos of lost family members. These objects are Hiroshima’s heritage, telling us about people’s lives in this city and how the atomic bomb ravaged their world.

Postcard conveys father’s anxiety over son’s fate

Masaharu Kiba, 81, a resident of Yamamoto, Minami Ward, Hiroshima, has kept an old, yellowing postcard for many years. Written in pencil, the words are fading in places. Some parts, including the sender’s name, were traced with a fountain pen by the sender himself. Mr. Kiba’s father, Yasuo, then 46, wrote the postcard on August 16, 1945, seeking the whereabouts of his wife and son. He died soon after, on September 2.

“I don’t know if Tomoko and Masaharu are alive or dead. Do you have any news about them?” Yasuo wrote these words while in a room at Kanon National School in the city suburbs (in today’s Saeki Ward), where those who were seriously injured in the bombing were brought, then had it sent to his brother-in-law. Tomoko, his wife, was 34 years old. By the time Masaharu obtained the postcard, both of his parents were dead.

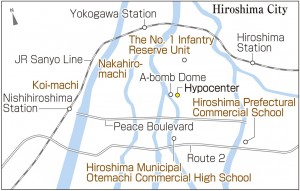

Masaharu was their only child. “I dug where our kitchen had been and found my mother’s bones,” he said. “I felt as if she was waiting for me.” He showed the spot, now part of the school yard of the Hiroshima Municipal Otemachi Commercial High School, located in Naka Ward. He said it was the first time he had visited this place in 69 years. “It looks completely different now, but I remember what our house was like,” he murmured, recalling the past. Back then, he was a first-year student at Hiroshima Prefectural Commercial School (now Hiroshima Prefectural Commercial High School).

On the morning of August 6, 1945, Masaharu’s father went to his workplace, a bicycle delivery service, in Yokogawa-cho (part of today’s Nishi Ward). Because the day before was Masaharu’s birthday, his mother had cooked his favorite omelet and put it in his lunch box. “I’m going now,” he said, the last words he ever spoke to his mother.

When the bomb exploded, Masaharu was standing in line in the school yard. The school was then located in Minamai-machi (part of today’s Minami Ward). “I was blown off my feet, and my face felt sizzling hot,” he said. He was taken to Oko National School (now Oko Elementary School), which was used as a relief station, and several days later he was moved to a Buddhist temple in the village of Suzuhari (part of today’s Asakita Ward).

“I’m sure my father did what he could to find us,” he said. The postcard continues: “I’m burned, and both my legs are hurt. I don’t think I can return to the city for at least a week.” In mid-September, Masaharu’s maternal grandmother found him at the temple and told him that his father, Yasuo, was dead. After the relief station at the temple closed, Masaharu went back to where his house had stood. It was November, and when he dug into the ground and found the bones, he knew that his mother, Tomoko, had died, too.

He was now an orphan, and led a hard life after the war. He had to quit school and find a job where he would also be given a room. He worked at a succession of places, including a furniture store, a construction company, and a confectionary wholesaler. One of his workplaces even went bankrupt. Out of his low wages, he saved money to go to high school at night and he opened his own confectionary wholesaler at the age of 22. He was introduced to his wife by a friend in the same business and was 25 when they wed. He and his wife, Misae, 81, have a son and a daughter, and six grandchildren.

Mr. Kiba did not share much about the atomic bombing with his children or grandchildren, but three years ago, he was asked to talk about his experience at Yamamoto Elementary School, located in his neighborhood. When the children listened keenly to his words, he felt very glad that he had agreed to speak to them. Mr. Kiba decided to donate the postcard to “convey Hiroshima,” hoping that people would understand the reality of the atomic bombing. At the end of the letter he attached to the postcard, he wrote, “I am absolutely against war. I wish there was peace in the world.”

(Originally published on July 8, 2014)

In response to a call from the Chugoku Shimbun, asking for artifacts that can convey the tragedy of the bombing to future generations, people have shared a variety of items, including mementos of lost family members. These objects are Hiroshima’s heritage, telling us about people’s lives in this city and how the atomic bomb ravaged their world.

Postcard conveys father’s anxiety over son’s fate

Masaharu Kiba, 81, a resident of Yamamoto, Minami Ward, Hiroshima, has kept an old, yellowing postcard for many years. Written in pencil, the words are fading in places. Some parts, including the sender’s name, were traced with a fountain pen by the sender himself. Mr. Kiba’s father, Yasuo, then 46, wrote the postcard on August 16, 1945, seeking the whereabouts of his wife and son. He died soon after, on September 2.

“I don’t know if Tomoko and Masaharu are alive or dead. Do you have any news about them?” Yasuo wrote these words while in a room at Kanon National School in the city suburbs (in today’s Saeki Ward), where those who were seriously injured in the bombing were brought, then had it sent to his brother-in-law. Tomoko, his wife, was 34 years old. By the time Masaharu obtained the postcard, both of his parents were dead.

Masaharu was their only child. “I dug where our kitchen had been and found my mother’s bones,” he said. “I felt as if she was waiting for me.” He showed the spot, now part of the school yard of the Hiroshima Municipal Otemachi Commercial High School, located in Naka Ward. He said it was the first time he had visited this place in 69 years. “It looks completely different now, but I remember what our house was like,” he murmured, recalling the past. Back then, he was a first-year student at Hiroshima Prefectural Commercial School (now Hiroshima Prefectural Commercial High School).

On the morning of August 6, 1945, Masaharu’s father went to his workplace, a bicycle delivery service, in Yokogawa-cho (part of today’s Nishi Ward). Because the day before was Masaharu’s birthday, his mother had cooked his favorite omelet and put it in his lunch box. “I’m going now,” he said, the last words he ever spoke to his mother.

When the bomb exploded, Masaharu was standing in line in the school yard. The school was then located in Minamai-machi (part of today’s Minami Ward). “I was blown off my feet, and my face felt sizzling hot,” he said. He was taken to Oko National School (now Oko Elementary School), which was used as a relief station, and several days later he was moved to a Buddhist temple in the village of Suzuhari (part of today’s Asakita Ward).

“I’m sure my father did what he could to find us,” he said. The postcard continues: “I’m burned, and both my legs are hurt. I don’t think I can return to the city for at least a week.” In mid-September, Masaharu’s maternal grandmother found him at the temple and told him that his father, Yasuo, was dead. After the relief station at the temple closed, Masaharu went back to where his house had stood. It was November, and when he dug into the ground and found the bones, he knew that his mother, Tomoko, had died, too.

He was now an orphan, and led a hard life after the war. He had to quit school and find a job where he would also be given a room. He worked at a succession of places, including a furniture store, a construction company, and a confectionary wholesaler. One of his workplaces even went bankrupt. Out of his low wages, he saved money to go to high school at night and he opened his own confectionary wholesaler at the age of 22. He was introduced to his wife by a friend in the same business and was 25 when they wed. He and his wife, Misae, 81, have a son and a daughter, and six grandchildren.

Mr. Kiba did not share much about the atomic bombing with his children or grandchildren, but three years ago, he was asked to talk about his experience at Yamamoto Elementary School, located in his neighborhood. When the children listened keenly to his words, he felt very glad that he had agreed to speak to them. Mr. Kiba decided to donate the postcard to “convey Hiroshima,” hoping that people would understand the reality of the atomic bombing. At the end of the letter he attached to the postcard, he wrote, “I am absolutely against war. I wish there was peace in the world.”

(Originally published on July 8, 2014)

-215x300.jpg)