Hiroshima: 70 Years After the A-bombing: Paper Monuments (Introduction)

Jan. 27, 2015

Accounts by A-bomb survivors sound alarm bell to future generations

What transpired that day of August 6, 1945? Does what happened have implications for today, 70 years later? There have been ongoing efforts to preserve the memory of Hiroshima’s experience through written accounts by the survivors. Since spoken words alone cannot achieve this end, their experiences have been recorded in writing. Their accounts, which depict events that should not be experienced by human beings, are a wake-up call for humanity and its future. These words put down by ordinary citizens must not be lost to history; they should be read by others and given proper reflection. This article explores how these “paper monuments” came into being, and how they have been handed down from generation to generation.

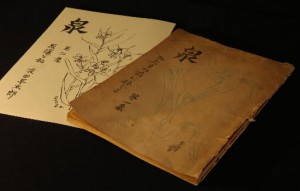

Izumi: Mitamano maeni sasaguru (Fountain: Offers Made to the Spirits of the Dead), published in 1946

Feeling guilt over having survived

A picture of a spiderwort plant was drawn on the cover of this collection of written accounts of the atomic bombing, because purple was the color of the school flag. Printed on rough paper, Izumi: Mitamano maeni sasaguru (Fountain: Offers Made to the Spirits of the Dead), compiled by students at First Hiroshima Prefectural Junior High School, was published in Hiroshima in August 1946, one year after the bombing.

“Those of us who survived among the members of classroom 35 suggested that accounts be collected in memory of our classmates,” said Heitaro Hamada, 84, who says he cheated death that day. “We asked the president of Hiroshima Aircraft, where we worked as mobilized students, to pay for the printing cost for 100 copies.”

Mr. Hamada, a resident of Nishi Ward, said he has always been haunted by a sense of guilt over the fact that he survived. Through an investigation that lasted decades, he found that, among the 59 students in classroom 35 (the fifth classroom of the third-year students), 42 were killed in the A-bomb blast.

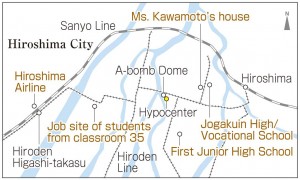

Of these 42, 38 were helping to dismantle buildings to create a fire lane in the Koami-cho area (now part of Naka Ward) and the other four were at the air defense facility at their school (now Kokutaiji High School).

Mr. Hamada had been working the previous day. Since he had just recovered from a chest ailment, he and Katsu Nakamoto (died in 2002), who was also feeling poorly, asked a classmate living in their neighborhood to report their absence on August 6. That spelled the difference between life and death.

Yorimi Sugo, 84, a resident of Higashi Ward, wrote a eulogy for Kazuo Higashi. Mr. Sugo said he is still tortured by guilt whenever he thinks of the atomic bombing.

The students from classroom 35 worked at Hiroshima Airline, a manufacturer of fighter planes located in Furuta-machi (now part of Nishi Ward). They were dubbed the “shield squad.”

Mr. Sugo had passed the exam to become a student in a preparatory course for the Imperial Japanese Navy. On July 25, he was seen off by his classmates and left Hiroshima for Hofu, Yamaguchi Prefecture, to enter the Naval Communication School, where he later learned about the atomic bombing. “When I returned to school, I was too ashamed to see the parents of the dead students. Nakamoto felt the same way.”

Izumi consists of eulogies and tanka poems written for the victims of classroom 35 by 39 students from the school and First Hiroshima Prefectural Girls’ High School (now Minami High School), who also worked at the factory. One student described how the victims performed their work with the hope it would help keep the nation’s enemies at bay. Another imagined some of the victims reciting the Imperial Rescript to Soldiers and Sailors while other victims groaned in pain. The students vowed before their lost souls that they would strive to create a truly peaceful nation.

Izumi was the first collection of A-bomb accounts, but Mr. Hamada said, “We heard about democracy, but we still had the traditional emperor-centered view of history.” In those days, publishing materials about the atomic bombing was under the strict supervision of the General Headquarters (GHQ) of the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers. “I didn’t know about the censorship, so that’s why we were able to publish this collection,” Mr. Hamada said.

The only copy of Izumi known to exist was donated to Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum in 2008 by Shiro Nakayama, 84, a writer living in Beppu, Oita Prefecture. He was awarded the Nihon Essayist Club Prize for his 1993 book Genbakutei Orifushi (A-bomb Reflections). Although he was exposed to the bomb’s heat rays while helping tear down buildings near the west end of Tsurumi Bridge (located in present-day Naka Ward), he did not refer to his own experience, only writing about the conversations he had with classmates before they died in the bombing.

When interviewed, Mr. Nakayama recounted that he felt those who died were better off than he was, since he was left with ugly keloid scars on his face. “I felt such lethargy,” he said. Asked why he continues to write about his life after such an awful experience, he said, “Those who survived the atomic bombing have a duty to put down on paper what the dead could not.”

Mr. Hamada began writing about his sisters’ deaths in connection with the bombing, which he said he had avoided, when he was a teacher at a junior high school. He published the second collection of Izumi in 2012. This summer he plans to publish another collection of accounts by former students of other schools.

Since the time he was a student in junior high school, Mr. Sugo has been involved in the activities of the association of bereaved families of students of the school. As a member of the board of directors at an electric company, he has been leading a busy life. Despite his advanced age, he still helps make arrangements for, and attends, the annual memorial ceremony for the 353 students and 15 teachers who perished in the bombing.

These survivors think of the people who were caught up in the war of nations and fell victim to the atomic bombing. With thoughts of peace and the future, they hope that future generations will be swayed by their outpouring of emotion, as the title of the collection suggests.

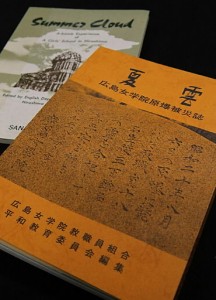

Summer Cloud, published in 1973

Students relive A-bomb experiences

By reading the accounts of survivors, people can feel a closer connection to those who experienced the bombing firsthand and receive their thoughts and wishes. One way of doing this is by holding recitation plays based on these accounts.

Students at Hiroshima Jogakuin University will perform an annual recitation play this summer. The play is based on Summer Cloud, the university’s collection of A-bomb accounts. A total of 350 students at Hiroshima Jogakuin High School and its vocational school, which grew into today’s junior college, fell victim to the atomic bomb. Many of them died while they were helping to tear down buildings near Hiroshima City Hall or became crushed under the collapsed wooden school building in the Kami-nagarekawa area (now part of Naka Ward).

Summer Cloud, which consists of 34 accounts by former students, teachers, and relatives of victims, was compiled by the teachers’ union of the school in 1973. According to a statement made then, the book was published out of fear that the survivors’ memories would be lost amid the nation’s excitement over the rapid economic growth taking place at that time.

The book has been used in peace education classes at Hiroshima Jogakuin Junior & Senior High School, and the university began staging a recitation play titled “We Will Not Forget the Summer Cloud” in 2003. The play has since been presented at school reunions and at elementary schools. In 2009, the university started performing the play during a peace studies program which brought together students from Christian schools in western Japan.

In the play, which also relates the history of the Hiroshima school, there is a scene where a 15-year-old girl digs through the rubble where her house has burned down.

“My mother died,” the lines begin. “When I found her bones, I cried and cried. I cried my eyes out. It wasn’t sadness, though. I thought, ‘Why did you have to die? Why didn’t you run from the house? You were stupid. My sister was stupid, too.’”

These words were written by Kazuko Kawamoto (nee Fujikawa), 84, a resident of Yokohama, who was then a fourth-year student at Jogakuin High School. Her house was located in the Teppo area (now part of Naka Ward) to the south of her school. On August 7, the day after the bombing, she went back to where her house once stood from Toyo Kogyo (now Mazda Motor Corporation), where she was working.

Eight members of her family lost their lives, including her mother Yasuno, 54, her sister Masayo, 22, another sister Akie Higuchi, 32, and a nephew and niece. Ms. Higuchi was staying with her mother after her husband was called up for military service. Ms. Kawamoto’s father had already passed away due to illness. After graduating from school, she got a job at a construction company with the help of her demobilized brother. Later she got married and settled in Yokohama.

She was determined to live a forward-looking life and locked away her memories of the atomic bombing. Raising two boys and a girl, she felt fulfilled. But when she was asked to contribute an account to Summer Cloud, she took up her pen. Her belief that no one else should ever be forced to write about such terrible experiences was stronger than her hesitation.

Ms. Kawamoto was asked to visit Hiroshima and she met with the university students who will appear in the recitation play: Miyu Tanaka, 21, a junior, Shiori Shibata, 19, a sophomore, and Kana Shirai, 18, a freshman. Ms. Shibata’s grandfather experienced the atomic bombing, but the other two have no family members with this experience.

Ms. Tanaka, who took part in the play last year, too, explained the efforts they have been making. “We’ve been holding discussions and trying to gain a better understanding of the message of your account,” she said. Ms. Shibata and Ms. Shirai listened to Ms. Tanaka, nodding in agreement, but they told Ms.

Kawamoto that they feel frustrated that they “can’t fully imagine the heat, odors, and the many other details that you experienced on that day.”

After listening to the students, Ms. Kawamoto told them, “You don’t have to force yourself to imagine what it was like. It’s all right if you take in what you understand. Live a good life and don’t repeat the history of heartbreaking separations with family and friends.”

Satoru Ubuki, 68, a resident of Kure, Hiroshima Prefecture, appeared in the first recitation play in 2003 when he was a professor at the university. He said, “It was very different from just reading, and our efforts and understanding were put to the test.” Mr. Ubuki hopes that more recitation plays will be performed so that A-bomb experiences will be “handed down by the reciters and the audience members.” Mr. Ubuki, who compiled Genbaku Shuki Keisai Tosho Zasshi Somokuroku (General Catalog of Books and Magazines Carrying A-Bomb Survivors’ Essays), is now trying to locate other accounts written after the publication of the book in 1999.

These A-bomb accounts are written testimonies of the human tragedy brought about by the use of a nuclear weapon. They are also records and memories which should be carried into the future. When read aloud, memories of the dead return to life, and the thoughts of the survivors are conveyed.

(Originally published on January 12, 2015)