Hiroshima: 70 Years After the A-bombing: Depicting the A-bombing: Introduction

Sep. 19, 2014

The day of the A-bombing Transcending time

The artwork produced by survivors of the atomic bombing depicts what they experienced and scenes that they witnessed on August 6, 1945. The works of art illustrating the terrible sights that are etched into their memories serve as both records of the event itself and of the survivors’ recollections. Most of these works were created immediately after the atomic bombing, but in recent years others have been produced by high school students based on the accounts of survivors. The collection of the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum includes 4,972 works of art that have been donated to the museum. This series looks at the reality of the atomic bombing as depicted in both old and new works of art and the feelings that imbue these works.

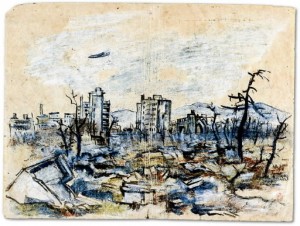

Ruins one month after the A-bombing

Deaf artist’s desire to leave record for future generations

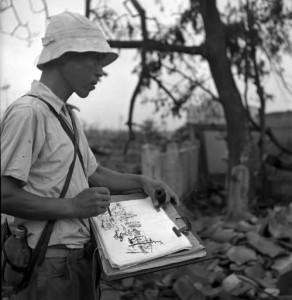

In 2008, 18 original works depicting the atomic bombing drawn on rough paper were donated to the Peace Memorial Museum. One depicts the mushroom cloud looming in the skies over Hiroshima. Others show the devastation in the Hatchobori, Nakajima and Funairi areas of the city and the remains of the Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall (now the A-Bomb Dome). While painting amid the devastation, the artist was captured on film by a photographer with the U.S. military.

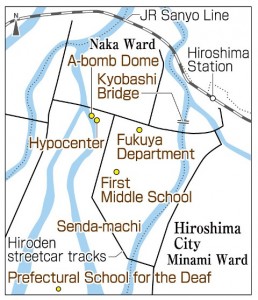

The pictures are the work of Keizo Takamasu (1901-1985), an art teacher at the Prefectural School for the Deaf (now the Hiroshima Minami Special Needs School in Naka Ward). His pen name was Keiso.

“The picture of the mushroom cloud was drawn as seen from Yoshida-cho (now part of the city of Akitakata), where the school for the deaf had relocated to escape air raids. The 17 drawings of the devastation were done while I accompanied my dad as he walked around Hiroshima,” said Mr. Takamasu’s son, Fumio, 78, who donated his father’s artwork to the museum.

During a visit to his Chiba Prefecture home, Fumio pulled out the diary he kept in 1945 in which he set down a detailed description of his father’s activities and his own feelings. Amid the unprecedented chaos in the aftermath of the A-bombing, why did Mr. Takamasu head out with his son to depict the devastation despite his handicap? The answer is partly related to his experiences in the 1923 Great Kanto Earthquake as depicted in a picture scroll Fumio has kept.

Born in Tokyo, Mr. Takamasu lost his hearing in an accident when he was a small boy. He learned how to read lips and to speak under the oral method of instruction. His ambition was to become a Japanese-style painter. He created a picture scroll of scenes in the aftermath of the Great Kanto Earthquake in which about 140,000 people were killed. After completing a teaching course at the national Tokyo School for the Deaf and Dumb in Tokyo in 1925, he was assigned to Hiroshima.

“My mother, Kameyo, died the year before the atomic bombing, and the school for the deaf had relocated [in April 1945] to avoid air raids, so my father took my sister and me to Yoshida-cho,” Fumio recalled. The school’s 98 students resided at three Buddhist temples in the town.

Fumio’s diary entry for August 6 says, “I was making a pair of sandals when there was a flash and then a noise.” The flash was visible even 45 km from Hiroshima. On the back of a piece of the rough paper used at the school Mr. Takamasu drew a picture of the pink mushroom cloud rising beyond the mountains.

He came to devastated Hiroshima with his two children on August 14. His home, which was near the school for the deaf about 2.7 km south of the hypocenter, escaped the fires, but the schoolyard was stained with the blood of the many wounded who were brought there. Mr. Takamasu took his ink bottle and drawing board and headed out into the ruins.

From Fumio’s diary entry for September 9: “Dad drew a picture of Hiroshima Station. Then, while he was drawing a picture looking west, an American newspaperman came up to him, took three pictures and did an American-style salute.”

Further investigation revealed that the man who took the photos was Wayne Miller (1918-2013), a photographer with the U.S. Navy. In the 1960s he served as president of Magnum Photos, a cooperative of prominent photographers. Mr. Miller came to Hiroshima with a photographer for “Life” magazine.

In Yoshida-cho Fumio had interpreted for his father when they went shopping and on other occasions, but he went along with his father to draw the devastation in Hiroshima “just in case.” “When he saw American soldiers, Dad told me to hide,” Fumio said.

Mr. Takamasu vividly recalled an incident just after the Great Kanto Earthquake in which a deaf friend was shot and killed by a military policeman who believed he was a spy. He also risked his life to depict the aftermath of the atomic bombing.

The series of drawings by Mr. Takamasu entitled “A-bomb Sketches” were displayed in the old Chugoku Shimbun Hall (in what is now Ebisu-cho, Naka Ward) in August 1954, when the city was undergoing a construction boom. Mr. Takamasu later touched up the original pictures and donated them to the Peace Memorial Museum.

In his later years as well, Mr. Takamasu, who lived in the city with Fumio and his family, made sketches based on his recollections of the devastation from the A-bombing. A picture he drew while hospitalized in 1983 carries this inscription: “I took my son with me and sketched the city for three days to make a permanent record for future generations of the scenes of complete and utter destruction.”

Mr. Takamasu’s daughter, Hiroshima resident Utako Tamaru, 81, became a teacher at the Hiroshima School for the Deaf. As her father would have wished, she talks about the atomic bombing using color copies of his sketches. “My father may be dead, but his pictures live on,” she said.

Passing on memories

High school student: “Painful for me too”

“I’ll Never Forget Those Eyes” is one of a number of oil paintings of atomic bombing experiences created by survivors and high school students in a collaboration that transcends time. The painting was done by Sora Tomita, 20, two years ago when she was a third-year student at Motomachi High School. It is based on the account of an event experienced by Hiroshima resident Mitsuo Kodama, 81.

“She really grasped my feelings,” Mr. Kodama said. At Ms. Tomita’s request, Mr. Kodama got together with her again in August, when she was home from college, and he told her that he was putting the painting to use when talking about his A-bombing experiences. Ms. Tomita is now a second-year student at Tokyo University of the Arts majoring in inter-media art. She told Mr. Kodama, who has overcome the effects of the atomic bombing, that she would like to paint his portrait.

The two first met through a project in a creative expression class at Ms. Tomita’s high school. Since 2007 students in the class have created works of art based on interviews with atomic bomb survivors. One goal of the project is to pass on the survivors’ stories. So far 56 works of art have been produced.

There are no atomic bomb survivors in Ms. Tomita’s family, and until she met Mr. Kodama, the Kure resident had merely heard a survivor’s story during a junior high school peace education class. But the slight interest in the subject she developed as a result motivated her to take part in her school’s project. With the assistance of the Peace Memorial Museum, which cooperated in the endeavor, she was paired with Mr. Kodama.

At the time of the atomic bombing Mr. Kodama was at Hiroshima First Middle School (now Kokutaiji High School), whose main gate was about 800 meters from the hypocenter. He was a first-year student. Of the 320 students in his class, 288 died while working on the demolition of buildings near the school or in the vicinity of city hall.

During his career as a company employee, Mr. Kodama suffered from colon cancer. Despite undergoing surgery 19 times, he continued to talk about his A-bombing experiences out of a desire to convey them to the younger generation. At first he had doubts about working with a high school student on artwork related to his A-bombing experiences because he felt it would be too painful to describe his experiences.

When First Middle School reopened after the war, Mr. Kodama entered the art department. He enjoyed both creating and looking at art. But he told Shu Kataoka (died 1997), a fellow survivor, art student and classmate, that “the A-bombing was so miserable and pitiful I couldn’t draw it.” Mr. Kataoka later became a well-known graphic designer. His poster-style depictions of the A-bombing emphasized abstractness.

It took about six months for Ms. Tomita to produce her painting based on Mr. Kodama’s account. In addition to meeting with her at school, he invited her to his home five or six times to talk about his A-bombing experiences. In order to better understand his feelings, Ms. Tomita read the notes Mr. Kodama made at the time and asked him a lot of questions. She repeatedly made changes after showing him a rough sketch and asking for his feedback.

“I’ll Never Forget Those Eyes” depicts a middle-aged woman trapped under a collapsed wall grabbing Mr. Kodama’s leg as she begs for help. The incident took place in Senda-machi (now part of Naka Ward) after the 12-year-old Mr. Kodama had crawled out from under his destroyed school building and was fleeing.

“I still regret pulling away from her grasp,” Mr. Kodama said. “Her expression was not only one of fear,” he added. His unvarnished account of the incident made a strong impression on Ms. Tomita. While painting the scene, she imagined that the woman must have been desperate to see her family. As she did so and made changes to her painting, “the feelings of Mr. Kodama and the woman became mixed with mine, and it was painful for me too,” she said.

Since the painting was completed, every time Mr. Kodama talks about his A-bombing experiences, he refers to an image of it that he uses in his presentation. “I want young people to understand the absurdity of war, which led to the deaths of many of my classmates in the A-bombing, and to recognize that these kinds of terrible things can happen to ordinary people,” he said.

Ms. Tomita looks at it this way: “It is difficult to accurately depict a scene that happened almost 70 years ago. But when you listen to the person’s account and draw the picture, you can experience that person’s feelings.” She said she hopes that those who see her painting will have a similar experience and that the painting will become a “bridge” to Mr. Kodama’s feelings.

Mr. Kodama, the other collaborator in this effort, described the meaning of this new work of A-bombing art this way: “A young person allowed me to reveal the feelings I had kept inside, and those feelings will be preserved in a tangible way.” He plans to collaborate on another work of art with a student at Ms. Tomita’s alma mater.

(Originally published on September 8, 2014)