Hiroshima: 70 Years After the A-bombing: Vanished neighborhoods 1

Jul. 8, 2014

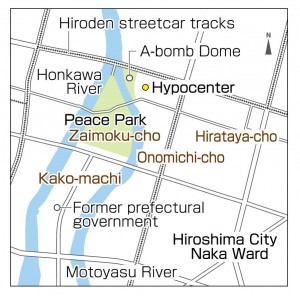

Kako-machi and Zaimoku-cho (now Nakajima-cho, Naka Ward)

The atomic bombing not only took the lives of many people but also cut survivors’ bonds with family members and upended their day-to-day lives. In order to rebuild their lives, those who had lost everything were forced to leave the devastated neighborhoods of Hiroshima in which they had grown up. As the re-demarcation of the city, a critical element of its reconstruction, proceeded, the names of old neighborhoods such as Kako-machi, Zaimoku-cho, Onomichi-cho and Hirataya-cho vanished. Lost amid the downtown area of Hiroshima, which now boasts a population of 1.18 million, are hometowns etched in the memories and in the belongings of those who once lived there.

Bearing witness: Sadness and fond memories

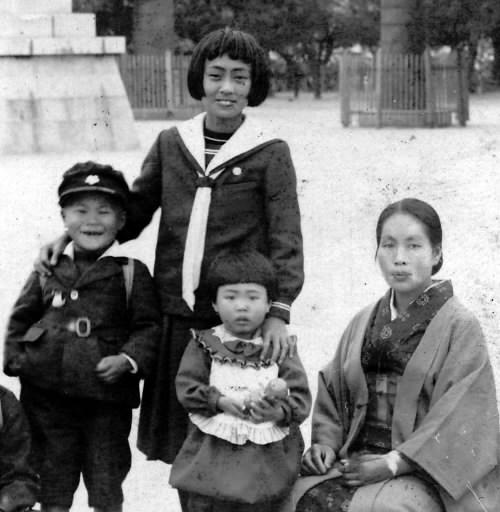

For Hiroshima resident Fukiko Kushima, 79, Peace Memorial Park holds both sadness and fond memories. Her mother and sister died in the atomic bombing in Zaimoku-cho, which is now part of the park. “I don’t want to be reminded of it, so I generally avoid going through the park,” she said. Sitting on a bench in the park in response to our request, she recalled her childhood in Zaimoku-cho and said it was the happiest time of her life.

Ms. Kushima was born and raised in Kako-machi, which was located just south of where the park is now. Across from her house were the prefectural government offices and prefectural hospital as well as Yorakuen, a garden built during the rule of the Asano clan. Even after the outbreak of war with the United States, Ms. Kushima, the youngest of four children, scampered around the garden and picked wildflowers there. In the summer she swam in the Motoyasu River, which was spanned by the Yorozuyo Bridge, commonly referred to as the “Prefectural Offices Bridge.”

But the war situation began to deteriorate, and in April 1945, just after Ms. Kushima entered the fifth grade at Nakajima National School (now Nakajima Elementary School), she and other children relocated to Shohoji Temple in Mirasaka-cho (now part of the city of Miyoshi). Ms. Kushima missed her family and treasures letters she received from them then, which said things like “We talk about you all the time” and “We must stay the course until the day of victory.”

Ms. Kushima recalled a visit from her mother, Tome, 44. “She came to see me in July, bringing my favorite sushi roll, which she had made for me. She smiled as she watched me eat it.” Ms. Kushima’s sister Hiroe, 20, came along. She never saw either of them again.

In anticipation of air raids, the city ordered the demolition of buildings to create fire breaks. The sixth phase of this effort, which encompassed the vicinity of Kako-machi near the prefectural government offices, got underway in late July. Ms. Kushima’s family moved to Zaimoku-cho.

Ms. Kushima’s mother and sister are believed to have been at the house in Zaimoku-cho on the morning of August 6, 1945. Her father, Ensuke, 50, was visiting her brother Toshiaki, 18, in Kyoto, where he was going to school. He immediately returned to Hiroshima to search for the remains of his wife and daughter, but they were never found.

When Ms. Kushima returned from the temple, she walked from Hiroshima Station to the home of relatives in Furuta-machi (now part of Nishi Ward). At the West Military Drill Ground (now the site of the prefectural offices) the charred bodies of horses were lying about, and people with skin hanging down their backs were collecting water. At the home of her relatives, her brother Masafumi, 13, a first-year student at Sanyo Junior High School, lay in bed. He had been working on the demolition of buildings in Zakoba-cho (now Kokutaiji-machi, Naka Ward) when the atomic bomb was dropped. He died on August 24.

After the war Ms. Kushima lived with her father and brother. Her father became a broker of tea ceremony utensils, which he was interested in. Ms. Kushima studied tea ceremony and helped her father. Her brother died in 1976, and her father died in 1989. Since then she has lived alone.

At her home she uses a sake flask her father found on the site of the house in Zaimoku-cho as a flower vase. Her father donated a melted bottle and other items to the Peace Memorial Museum, but he continued to use the cracked sake flask. “I suppose he found it hard to give up something that my mother and sister had used,” Ms. Kushima said. She is thinking of donating the sake flask, which bears witness to her family life, to the museum too. “It would be sad if it were broken after I’m gone,” she said.

(Originally published on March 3, 2014)