Feature 1: Radioactive Contamination in Greenland

Dec. 20, 2012

Chapter 1: The United States

On January 21, 1968, an American B-52 strategic bomber carrying four hydrogen bombs crashed into the ice near Thule Air Base in northwest Greenland. The explosives used to ignite the bombs detonated on impact, causing the dispersal of plutonium and other radioactive materials over a wide area. Twenty years after the accident, the high incidence of skin cancer detected among Danish workers who were employed in the cleanup operation serves as a reminder of the danger of exposure to radiation.

Contaminated Snow

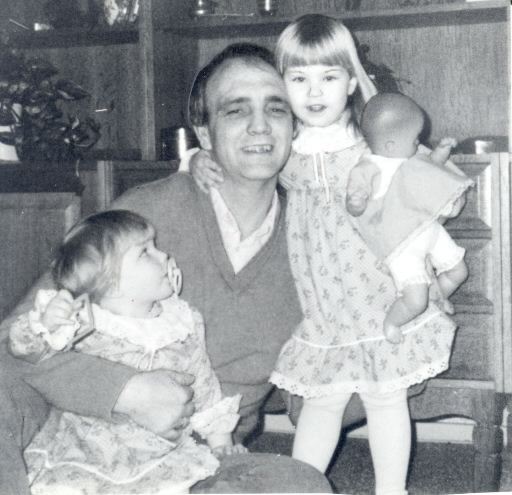

Ole Markussen, aged fifty-one, is the leader of the former workers at Thule Air Base. We spoke to him at his apartment in a Copenhagen suburb, where he lives with his wife, Sally, without whose care he would be forced to stay in a hospital. Quietly he launched into an explanation of what had happened on that day in 1968.

"I was taking a nap in the barracks when I was woken by a terrific boom. I rushed outside to see what had happened and found the area lit up by pillars of fire shooting up into the sky." He returned to the barracks and switched on his radio. "After half an hour or so, the news came over that there had been a plane crash, but there was no mention of any hydrogen bombs," he continued.

The accident occurred at 5:40 in the afternoon. Being winter in the Arctic Circle, it was dark all day. A few of the truck drivers got together and drove out into the pitch darkness to see if they could rescue any of the crew. Markussen and most of the other workers stayed in their rooms. Six hours after the accident there was a fierce blizzard which blew contaminated snow from the accident site into the barracks seven miles away. Markussen believes that the plutonium made its way into his system via this snow.

"The U.S. Air Force has never made public the amount of radioactive material that was released that day. There's no way they should be able to get away with that." By this time our host was shaking with rage.

The plane wreckage, along with the shattered bombs, was disposed of in just over a month. Until the sun appeared in spring, however, nothing could be done about the twenty-two square miles of contaminated snow and ice, and it wasn't until March that the cleanup was begun in earnest. This operation also took about a month. Markussen's work in the transport division involved supervising the men who were repairing the heavy vehicles contaminated by the radiation. He continued to work at the base for four years after the crash, and during that time experienced no health problems. It was at the beginning of 1980 that he first began to notice changes in his body.

"The skin on my legs turned black and they swelled up," he told us. "The doctor had never seen anything like it before." Markussen experienced a constant feeling of tiredness and in 1984 collapsed with a brain hemorrhage while at work. He has since been in hospital eight times. His left leg is paralyzed from the knee down and he has also developed a speech impediment.

The couple knew that a number of Markussen's friends from his days at the base were suffering from the same kind of ailments. In February 1986 they went on television to tell the public about the terrible effects that exposure to radiation had had on their lives.

"I got in touch with the people I worked with in those days, and together we demanded that the government conduct an investigation," Markussen said. Including the widows of some of his former acquaintances, the couple received almost four hundred replies. Skin conditions, loss of sense of balance, mental illnesses... the situation was far more serious than they had ever imagined. At the time of the accident, there were 1,202 Danish workers at the Thule Air Base. By July 1989, 214 had died. In the case of six of the fourteen who passed away in the first half of 1989, the cause of death was cancer.

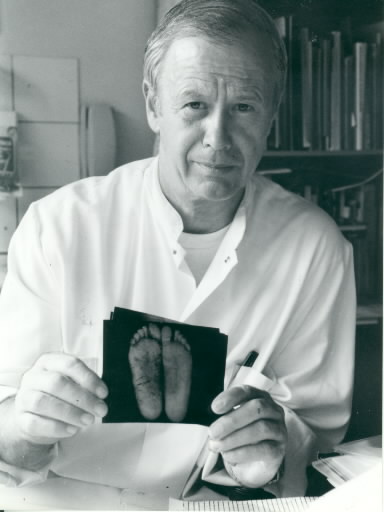

We interviewed Hugh Zuchariae, head of the Department of Dermatology at Marselisborg Hospital in Aarhus. Zuchariae is involved in the treatment of Thule's former workers. His twenty-seven patients suffer from skin diseases that include rashes on their hands, arms, and the soles of their feet; he has diagnosed two as having skin cancer. Of the twenty-seven, five were involved directly in cleaning up the radioactive contamination at the base.

"As there's no data concerning the amount of plutonium that was scattered and the extent of exposure to radiation, it's impossible to say for certain that their skin diseases have any connection with radiation. But it's clear that men who have worked at Thule do show a higher rate of skin disease than normal," said Dr. Zuchariae, choosing his words carefully.

Workers Advised Not to Have Children

We met the widow of Arleng Hogsted, one of Markussen's former colleagues, at a Copenhagen hotel. Her husband had died at the age of forty-three, leaving her with four handicapped daughters.

"Where would you like me to start?" she asked. Maya Hogsted was a striking woman, but she looked tired and drawn, and the lines on her face spoke volumes about the hardship she had to face each day.

"We got married in 1972, just after Arleng got back from Thule." Hogsted had returned from the base with red spots covering his arms and legs. "He worked at Thule from January 1968 until April 1972," she continued. "I know he was an electrician but I'm not sure exactly what he did—he never talked about it much."

The Hogsteds' first daughter was born in 1973. Her legs were abnormally short and she had defective vision. Their next child, born four years later, had a heart attack after its first birthday which resulted in brain damage. The two youngest children, born in 1981 and 1982, also have heart problems and are physically handicapped. Arleng's own health deteriorated with each passing year, until he was experiencing severe pain in almost every part of his body.

Arleng rarely spoke of his years in Greenland, but one day he told his wife that there had been a fatal accident at the base and that the base doctor had told him it would be better not to have children. Maya did not make the connection between radiation and the illnesses of her husband and daughters until a letter arrived from his old friend, Ole. For the first time, she realized that the accident her husband had referred to had involved radioactive material.

By this time, however, her husband was already dead. "Arleng died in January 1985. He'd been on morphine for a long time by then."

Maya would probably never have had any children if she had known the full story about the accident. With help from her parents she manages to look after her handicapped daughters. Her final words to us were spoken in tones of barely suppressed anger: "Our government should be demanding compensation from the American government through diplomatic channels. If they won't do that, then they should take steps to compensate the victims themselves."

After the plane crash in 1968, the remains of the hydrogen bombs and the aircraft were gathered up and placed in 217 large metal drums. Likewise, the contaminated ice and snow was put in sixty-seven tanks holding approximately twenty-five thousand gallons each. This enormous amount of material was taken back to the United States. In spite of this, the U.S. government is refusing to recognize any of the claims of the Danish workers at Thule, and the Danish government itself is taking a similar stance.