5. The Need for Independent Surveys

Jan. 11, 2013

Chapter 1: The United States

Part 2: Three Mile Island--Ten Years After

Part 2: Three Mile Island--Ten Years After

During our investigations in the vicinity of Three Mile Island, we often heard the name Dr. Tokuhata mentioned.

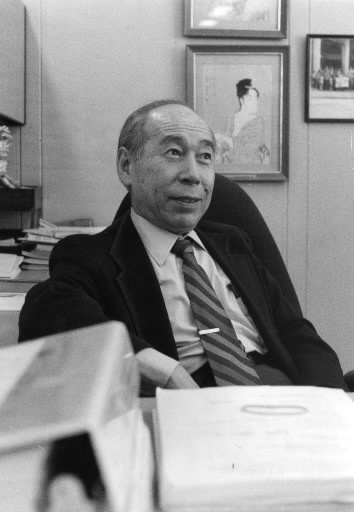

George Tokuhata was sixty-five years old, and had been living in the United States ever since he first came as a Fulbright scholar to study preventative medicine after the Second World War. After studying at a number of institutions, including Johns Hopkins University, he was invited to head the Epidemiological Research Division at the Pennsylvania Department of Health. "Since the accident, the focus of my work has been on nuclear power," he told us. We sat in his office, its walls decorated with Japanese ukiyo-e prints, while the doctor talked about his research over the previous ten years, which included a survey of the effects of the accident at Three Mile Island on the surrounding area.

The first news of the accident had arrived three hours after the initial breakdown of the water supply pumps. Tokuhata had rushed to his office before any other details were released, and had stayed there for two days without sleep to answer the inquiries of the media and the public concerning the possibility of exposure to radioactive material, and the time it would take for the situation to stabilize.

Tokuhata also met with experts from the DOE who had rushed up from Washington to deal with the crisis. At lunchtime on the third day they advised the governor to issue an evacuation warning. However, Tokuhata's real work started after the crisis had died down, when he was given the responsibility of conducting a survey of residents' health in the surrounding area. Unfortunately, the state government had taken no precautions such as preparing emergency funds or a skeleton staff to be made available in the event of a nuclear accident, so Tokuhata started his two surveys with the help of a grant from the federal government. The aim of one survey was to monitor the outward migration of the thirty-seven thousand people who lived within five miles of the plant, while that of the other was to monitor the condition of the four thousand pregnant women within ten miles of it.

A year after the accident, twelve percent of the residents were found to have moved away from the area. According to Tokuhata this is a normal figure for a highly mobile society such as the United States. Of the pregnant women surveyed, six hundred or fifteen percent were found to have suffered miscarriages. Again this was not seen by Tokuhata or his survey team to be a significant figure, as it corresponded with the rate of miscarriage outside the survey area. The radiation level within a ten-mile radius was found to be only 10 millirems on average. Tokuhata claimed that, as levels of 100 millirems per annum occur in areas of natural background radiation, it was impossible to imagine that any harm had been done to residents' health.

The results of these surveys have been heavily criticized by environmental groups. A team headed by one local resident, Jane Lee, carried out an independent survey which showed that in one section of the neighboring city of Middletown, the incidence of cancer had increased six fold in the ten years since the accident. In response to the criticism, Tokuhata widened the scope of his survey to include areas within a twenty-mile radius of the plant; but his team found no evidence of an increase in the number of cancer cases. Expressing mounting irritation at such different results, residents' groups have accused Dr. Tokuhata of being in league with those wishing to promote nuclear power. Their next move may be to take him to court on accusations of falsifying data. When asked about the breakdown in communication between himself and the local people since the accident, Tokuhata replied calmly:

"As a scientist, my duty is to carry out investigations rationally and accurately for future reference, and that's exactly what I've done." His furrowed brow spoke eloquently of the trials and tribulations of the last ten years.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

In the years since the accident at Three Mile Island, forty-six nuclear reactors have been put into operation. Five have been closed down, the construction of another sixty-nine has been canceled or delayed, and plans to build new reactors have been shelved. This seems to be America's only answer to the disaster.