3. Victim of the Uranium Rush

Jan. 18, 2013

Chapter 1: The United States

Part 3: Uranium Mining on the Navajo Reservation

Part 3: Uranium Mining on the Navajo Reservation

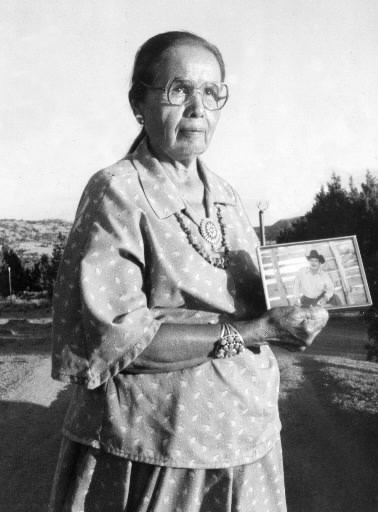

Behind Charley's determination to investigate radioactive contamination in the abandoned uranium mines lies a personal tragedy—the death of his father, Harris Charley, who died of a chest ailment in 1986 at the age of sixty-five. His widow showed us a photo of her husband; a strong, powerfully built man totally suited to the ten-gallon hat he was wearing. Mrs. Charley looked sadly at the picture. "Harris lost a lot of weight after he got sick. I reckon it was the mines that got him, you know..."

Charley's father was wounded and discharged from the navy around the time that uranium mining began in the nearby mountains in 1948, three years after the end of the war. The village had no other industries, so there was plenty of competition for jobs at the mines. Harris Charley, with eight children to support, went to work as soon as he recovered from his wounds.

At the beginning, his days were spent underground from morning till night. First the side of the mountain was dynamited, then the uranium was dug out of the resulting rubble. Harris was strong and popular with the other workers, so in time he was made a foreman, and he spent his days traveling around the mines. His chest ailment was discovered in 1964 when he had a medical after transferring to the Colorado mines. His widow confided to us that he had been complaining of shortness of breath for two or three years prior to the checkup. Following advice from his doctor, Harris gave up the mines and started work as a carpenter. His new trade was short-lived, however. Soon the Charley children, by this time grown-up, were doing their father's work for him. His condition worsened as time passed, until he had wasted away to two-thirds of his former weight, his powerful chest sunken by disease. Eventually he was taken to a Utah hospital.

Unbeknown to Harris, he had spent seventeen years digging up not only uranium but a number of other radioactive substances. Radon gas is particularly liable to accumulate in uranium mines, and is a well-known cause of lung ailments. The uranium dug out of the ground at Four Corners was first sent to a local refinery and then on to Oak Ridge, Tennessee, the home of the Hiroshima bomb. There the uranium was enriched and used in the manufacture of plutonium, which was then placed in a nuclear warhead.

"I don't think my father realized that what he was digging up was going to be used for making atomic bombs," Charley said. "As far as he was concerned it was just a funny-looking rock they were dealing with."

Charley consulted a lawyer and has recently managed to obtain official recognition that his father's death was caused by his work environment. According to the lawyer, Earl Mettler of Albuquerque, there have been approximately thirty similar cases to date. However, even though exposure to radiation was recognized as the cause of death, Charley will only be entitled to receive ordinary industrial accident compensation which only amounts to four or five hundred dollars a month. Charley explained why the ruling was unfair: "The benefit for work accidents is calculated on the salary at the time of the accident, in this case at the time of death. When you think of the length of time between when the person leaves work and when they die, the amount is meaningless. The Navajo are too proud to take a trifling allowance like that—we will demand proper compensation." In a low voice, the turquoise pendant around her neck quivering slightly, his mother added, "If they had made the environment safer to work in, Harris would be alive today."

Here was a family that had in a sense been sacrificed to the military ambitions of its leaders. In spite of this, a miniature Stars and Stripes still occupies pride of place in their living room.