7. Nevada-Semipalatinsk

Jan. 21, 2013

Chapter 2: Soviet Union

Part 1: The Largest Nuclear Test Site in the Nation

Part 1: The Largest Nuclear Test Site in the Nation

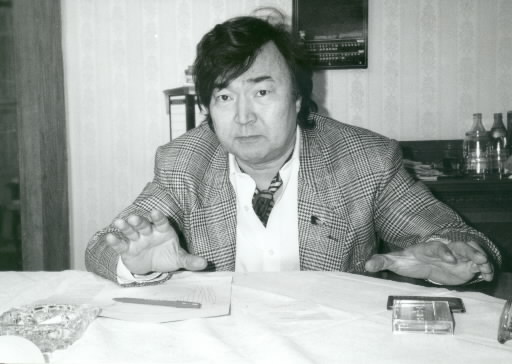

After leaving Semipalatinsk, we returned to Moscow via Alma-Ata, capital of Kazakhstan. Olzhas Suleymenov, chairman of Nevada-Semipalatinsk, who had gone to a great deal of effort to help us in our investigations, was also in the capital to attend a meeting of the People's Assembly to be inaugurated by Mikhail Gorbachev.

"Last year (1989), eleven of the eighteen underground tests scheduled were canceled," he told us. "For almost six months, since October, there have been no tests carried out at all. But if we let down our guard, the nuclear war against the people of Kazakhstan will start again." Suleymenov did not have to spell out his willingness to do all in his power to close the test site; his confident tones and determined look said enough.

Suleymenov was born and raised in Kazakhstan. In March 1989 he was elected to the People's Assembly, and he is also a member of the Supreme Soviet. We asked him about his speech on television in February of the previous year, which brought the anti-test movement into existence.

"It was a phone call from a soldier that made up my mind to give that speech, believe or not," he said. The caller informed him that radiation leaked during the tests on February 12 and February 17 had found its way to the military base at Kurchatov, over a hundred miles to the north.

"The fact that someone from the army itself was obviously worried about radiation—that's what convinced me."

The protest meeting on February 28, which led to the establishment of a movement to stop the testing, resulted in demands being voiced for assistance to radiation sufferers, the holding of a meeting in Karaaul on August 6, and speeches at the General Assembly demanding a halt to testing. The movement continues to grow rapidly as people begin to vent forty years of suppressed anxiety about nuclear tests.

The democratization of Eastern Europe is also providing great encouragement for Suleymenov and his colleagues in Kazakhstan, but they are only too aware that they cannot afford to relax their vigilance.

"The military would start testing again tomorrow if they could," he remarked grimly. "It's like a sword hanging over our heads."

An activist we spoke to in Semipalatinsk on March 11, 1990, told us gloomily: "Yesterday, the Americans conducted a nuclear test in Nevada. It'll probably give the hawks here an excuse to start testing again."

As the name of their anti-test movement suggests, the Soviet people know that until testing stops in Nevada, the sites in their own country will never be closed.

"That's why all the radiation sufferers of the world have to unite!" said Suleymenov excitedly. "Now that the barriers between East and West are coming down, we must show our solidarity and give the militarists of the world our message of peace."

Suleymenov's biggest worry is the unknown depths of the effects of radioactive contamination from the Semipalatinsk testing area. None of the information gathered in the year after the movement began gives any cause for optimism. Quite the reverse. Cancer at a level 3.4 times that of other districts; strontium concentrations on nearby farms 360 to 2,900 times the national average; stillbirths; infant mortality; deformities; leukemia; the depressing list goes on.

"You probably couldn't call it very scientific at the moment, but we have to decide quickly who needs to be helped. And we have to make an informed judgment about which areas are dangerous. We're determined to pursue the truth, whatever the cost. There are no national borders when it comes to suffering from radiation."