5. Reporting about Chernobyl

Jan. 23, 2013

Chapter 2: Soviet Union

Part 2: Chernobyl Three Years After

Part 2: Chernobyl Three Years After

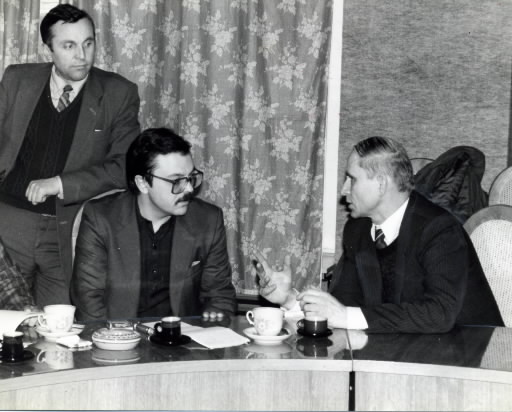

After our hurried trip to the northern Ukraine and the south of Belorussiya, we returned to Kiev to meet Vladimir Kolinko of the Ukraine office of the Novosti News Agency. He was introduced to us by our young Russian interpreter as the first journalist to go into Chernobyl after the accident.

Kolinko first heard about the accident on April 28—two days after it had occurred--via a Reuters dispatch from Stockholm which stated that there had been an accident at a nuclear power station in the Soviet Union. He had trouble getting permission to enter the affected area, so by the time he was able to make it to the scene, it was April 29. When his report finally made it onto the newsstands on May 4, eight days had passed since the explosion.

Using the nearby village of Kopati as a base, Kolinko spent two days covering the efforts of scientists and soldiers to seal in the radiation, and watching the rapid transformation of the city of Pripyat into a ghost town. During the course of his investigations, he himself was exposed to a radiation level of 100 rems, but fortunately he did not suffer from radiation sickness.

The day we visited Kolinko in his Kiev office, he had just completed an intensive four-week medical checkup. Although he was ashamed to admit it, he confessed to us that he had known virtually nothing about nuclear power or the effects of radiation until he did the articles on Chernobyl.

Of course, he was not the only journalist exposed to high doses of radiation. Journalists and cameramen from newspapers, news agencies, and television stations all exposed themselves to danger. There was Igor Kostin, a photographer and colleague of Kolinko's, who won a number of international awards for his photos of Chernobyl. And Leonid Muduk of Ukraine Television, who wrote the scripts for a series of four documentaries about the disaster. All of them had believed, as did the general public, that nuclear power was safe, and all had spent some part of their working lives helping to reassure others that it was. However, while they were writing articles on the victims of radiation, the sealing of reactor No. 4 in its concrete coffin, and all the other aspects of the disaster, they were able to experience at first hand the destructive power of radiation. Since they themselves had also been exposed to radiation, they could not help but change their views. Their accurate reporting of the Chernobyl disaster was made possible in part as a result of Mikhail Gorbachev's policy of glasnost.

Since the accident, journalists in Kiev have continued to keep a close watch on Chernobyl and have followed up their reports with investigations into the health of the residents in the contaminated areas and the safety of their food and water supplies.

An article by Kolinko, published in February 1989, reported an increase in the number of cancer patients as well as deformities in livestock born since Chernobyl. His methods, however, were branded unscientific by Moscow's medical community and he was criticized by the party newspaper, Pravda, for lacking in objectivity.

Kolinko has refused to give up the fight to expose the dangers of radiation. "Both the academics in Moscow and the reporters at Pravda are attacking me without even seeing for themselves the situation at Chernobyl. All I did was talk to the doctors and vets who are facing these facts every day. When I told them what I'd heard, they responded by questioning the competence of those doctors. It would seem that it's not me that's being unscientific, but my critics."

The material for the article in question was gathered in the Narodichi district of the Zhitomir region, between thirty and fifty-five miles from the accident site. Kolinko had been shocked to find animals with severe birth defects, such as pigs born without eyes. The article was written to draw attention to these occurrences, with the aim of prompting an investigation which would determine whether the defects were caused by radiation. In actual fact, soon after the article was published the government did carry out a hurried survey of the residents' health, as well as checks on soil and foodstuffs. The investigations resulted in an immediate evacuation order. There is no doubt that if Kolinko had not written the article, the residents would still be living in the same district, the unwitting victims of radioactive contamination.

"Academics and bureaucrats are far too optimistic about the effects of radiation. Unless we can get them to consider the people's health more, things are only going to get worse," he said, a note of impatience clearly discernible in his voice.