4. ‘We Just Want to Catch Live Fish, Not Dead Ones’

Feb. 21, 2013

Chapter 4: India, Malaysia, Korea

Part 1: Living in the Shadow of Indian Nuclear Development

Part 1: Living in the Shadow of Indian Nuclear Development

Sadres is a quiet fishing village home to less than five hundred people located at the southern end of the Kalpakkam Nuclear Complex. Poverty reigns there just as it does in Kokilyamedu, but the atmosphere of the village is a little different. Children were studying under a roof thatched with palm leaves, and next door was a small building belonging to the Bay of Bengal Fishermen's Union.

Inside were three young men. We told them the purpose of our visit and stepped inside. Lesson plans and antinuclear posters covered the gray walls of the building. The school was in fact administered by the union. "Why exactly are you against the nuclear facility?" we asked P., the secretary, getting straight to the point.

"We can't catch fish any more because of it, that's why," was the reply. "If you get hit by a wave while you're out fishing, you start to itch and the lower half of your body breaks out in blisters."

The boats are small, the largest being no more than a couple of tons. There was a time when crab, shrimp, shellfish, and a variety of multi-colored fish could be found in abundance near Sadres.

"The reason why our catches have declined so drastically is that plant. The warm waste water that comes out of there keeps the fish away—particularly in the area within a few miles radius of the outlet," P. remarked bitterly. "Lots of dead fish are floating out there," added one of his companions, a thick-set young man of about twenty. "We gather them up and make karuvadu."

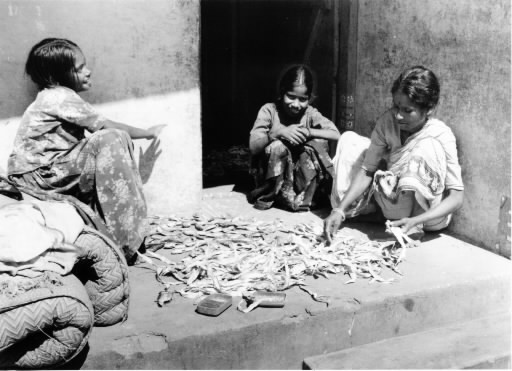

Karuvadu is a dish made by salting and drying fish for two or three days. We often saw the women and children of Sadres preparing the fish and laying them out to dry in front of their houses. "It all goes to market. People here won't touch the stuff because they know where it's come from," the young man continued, a trifle guiltily.

The villagers take their catch of karuvadu to Madras and sell it there, where it provides a cheap source of protein for the poor people in the city. We asked whether it was actually safe for people to eat this fish. "Well, they're probably contaminated, but we can't catch anything else, and there's hardly any money coming in at the moment. We don't have any choice," he said gloomily.

Under normal circumstances, the temperature of the sea around Kalpakkam is about 85°F. However, according to P., when both of the reactors are in operation the temperature at the outlet shoots up to 140° F, a dangerous level. The fishermen would start itching and begin to feel tired every time they went out to sea.

In an attempt to find out exactly why these things were happening, the union recently got hold of a booklet about radiation written in easy-to-understand Bengali. Its contents include explanations about gamma and beta rays, and the Chernobyl disaster. The men have started a study group in the village using this material. P. explained to us the mood of the people concerning this issue:

"The authorities don't tell us anything except that it's safe. But it's not surprising that the people start to worry when they hear about what happened at Chernobyl."

The villagers have tried countless times to bring attention to their decreasing catches, dead fish, and illnesses. The authorities, however, will have nothing to do with their claims, accusing them of some vague ulterior motive. The villagers' main quarrel with Kalpakkam is that it is making it extremely difficult for them to escape from the cycle of poverty in which they are trapped.

"We want to catch and sell good live fish, not dead ones!" the young man said, smiling for the first time since our interview began.

Caption: 4 In the fishing village of Sadres, women labor to make dried fish called “karuvadu.” Karuvadu may be contaminated, but the poor people of the cities who eat it are unaware of this danger.