5. Besieged by Radiation

Feb. 21, 2013

Chapter 4: India, Malaysia, Korea

Part 1: Living in the Shadow of Indian Nuclear Development

Part 1: Living in the Shadow of Indian Nuclear Development

Traveling north along the Bay of Bengal, we arrived in Calcutta. From there we made a five-hour train trip to the steel town of Jamshedpur, in the state of Bihar. Another two hours' drive up a winding mountain road brought us to within sight of the uranium mining village of Jadugoda.

"Let's get out here and have a look at the uranium tailing pond." Our guide for this section of the trip was the Jamshedpur journalist and chairman of the Society for Environmental Consciousness, Janak Deo Pandey. We hid our cameras in our bags and walked up the steep hill for about fifty yards. When we reached the top, below us we could see the pond and the piles of tailings, dry and cracked, enveloped in an eerie silence.

When uranium ore has been refined and the uranium oxide (yellowcake) extracted, the remaining rubble is sent down pipes to this tailing pond. The refinery, located half a mile away, reminded us of a small fortress. Directly below us we could see another village. "That's the place besieged by radiation," Pandey commented. Dungridi is a tiny hamlet of twenty-five households, home to 125 people.

Later we walked into the courtyard of one of the houses to find Mohan Majhi, a thin young man, sitting in the sun having his lunch. Aged twenty-one, he used to work at the uranium mine. Majhi's movements were slow and deliberate and his eyes bloodshot; he was obviously not in the best of health.

"I started getting fevers after about a month at the mine," he said weakly. "I stuck it out for a while, but after two months I couldn't work any more. The doctor there told me I had blood poisoning—I don't know exactly what he meant by that." He began to cough violently. Recently, he told us, he had no energy and was beginning to lose his sight.

"I can't do anything now except hang around at home." Majhi did not even receive a medical certificate. His wages stopped as soon as he left, and he has no money to buy medicine.

"Poor Mohan lost his father two years ago, to cancer of the tongue," Shamu Majhi said sympathetically. Shamu had just come off the night shift at the mine. Mahji added, "After fifteen years at the mine, he suddenly got cancer--he was only forty-five when he died." His mother, Salke, rubbed his back as he collapsed in another fit of coughing.

"My son was healthy too before he went to work in the mine," she said. "Everyone who works there ends up with something wrong with them." There are still three young children in the family, and following her husband's death, supporting the family became Mohan's responsibility as the eldest son. Since his health deteriorated, the family has had to eke out a living from the small patch of land it owns.

"My father worked at the mine, too—for twenty years," said Shamu, who was the local youth leader. "He's been bedridden for a long time now with a fever. Another miner died of cancer here two weeks ago. The same thing is happening in the next village." Shamu himself has been working in the mine for six years. He told us that recently he had started to feel a worrying tightness in his chest. "I went for my first checkup in six years the other day. But they wouldn't tell me the results."

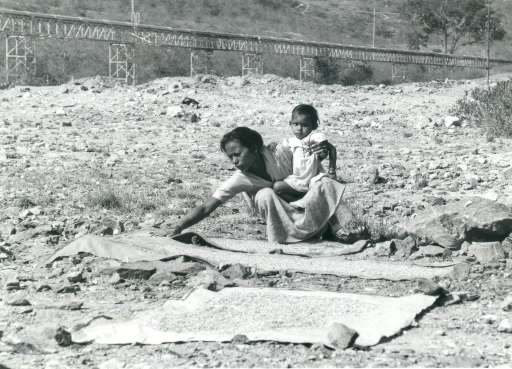

The men of these villages give up their lives in order to make a living for their families. However, it is not only the miners themselves who are affected. Walking around Dungridi, we realized that the contamination from the mines was spread over a wide area.

Simoti Majhi, aged eight, was standing beside one of her family's cows when we first saw her. She was wearing a torn green dress and had a towel wrapped round her head. She turned away shyly as we approached. "She's been plagued by this fever ever since she was three," her mother, Baso, told us, her brow creased with worry. "Not long after she first got it she started to lose all the feeling in her right hand. Now she can't pick anything up—she can't even lift her arm."

Simoti's shoulder blades stuck out sharply from her back. She wears the towel to cover her abnormally small head. Her eyes shifted from side to side, but she never looked straight at us. Simoti is also mute. "Simoti didn't even know her father had died," Baso sighed. Her husband, Chandrayi, had died three years previously at the age of forty-five, after three long years of illness during most of which he was bedridden. He had worked in the uranium mines for eighteen years. The doctors had said it was tuberculosis.

Near the Majhis' home lived another little girl, Jowa Soren. She was only eight months old, but when her father came out holding her, we noticed that her legs were abnormally thin. Her father, Mohan, a farmer explained that she had lost all the feeling in them when she was two months old.

"The doctor said it was polio, but she was inoculated soon after she was born, so I doubt that it can be." His wife nodded in agreement. "The air and water are poisonous around here," added Shamu Majhi, who was showing us around the village.

When the hot winds of summer blow, a material like ash is carried down into the village from the tailing pond. "When that stuff starts to blow down here, the whole village is filled with dust; it gets in our houses, on our food, it coats the crops in the fields--it's disgusting. And everyone coughs all the time," he continued.

The river water has become contaminated by the tailings pond, so the Uranium Corporation of India Limited (UCIL), which is under the direct jurisdiction of the Department of Atomic Energy, has recently installed a water pipe. Running directly above the water pipe is a three-foot-wide pipe used to transport uranium tailings; next to the water faucet we saw the women of the village washing dishes and doing their laundry. This is the only drinking water that is provided for the people of Dungridi.

At one stage during our visit to the village, a man called out to us and asked us what we were doing there. When we replied that we were investigating damage caused by radioactive contamination, he beamed and said confidently, "There's none of that here!" The man's name was Lal and he was in charge of the chemistry division at the mine. We asked him if the pond was really safe.

"Of course it is," was his reply. "All the tailings are chemically treated before they are released into the pond."

"But you must be aware that a lot of people are ill in the village?" we persisted.

"Oh, them. That lot are just ignorant... No matter how many times we tell them not to drink the river water or use it for washing, they never listen."

Perhaps Lal realized then that he had just contradicted his earlier assurances, because with these words he hurriedly started up his motorbike and drove away. On the edge of the village stood a small sign with the paint peeling off. With difficulty we could make out the words "Tailing Pond—Radioactive Zone. Trespassers Will Be Prosecuted."