8. The Radiation Coast

Feb. 22, 2013

Chapter 4: India, Malaysia, Korea

Part 1: Living in the Shadow of Indian Nuclear Development

Part 1: Living in the Shadow of Indian Nuclear Development

In the southern state of Kerala, facing the Arabian Sea, there is a beach known locally as "the radiation coast." The twenty-three-mile stretch of sand has a level of natural background radioactivity between five and fifty times the safe level set by the International Radiological Protection Board. This high level of radiation is caused by large deposits of monazite in the sand. At present the public corporation, Indian Rare Earths, is refining the sand to produce rare earths and thorium-232, which is used for nuclear fuel. The radioactive sand which the company collects from the area is posing a grave danger to the nearby residents.

We drove by jeep along the coast, passing small houses dotted among the palm trees, toward the village of Alappat. We were accompanied by V.T. Padmanabhan, coordinator of the Center for Industrial Safety and Environmental Concerns, a private research organization. The center has its office in Quilon City, and for the past few years it has been conducting health surveys in the area.

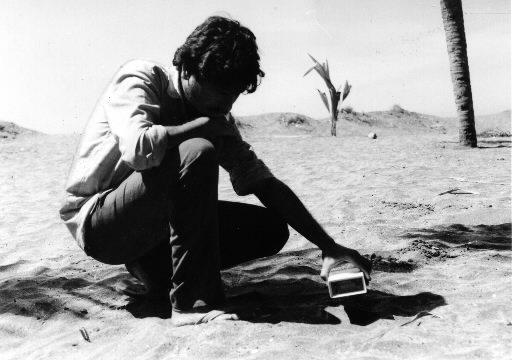

"Let's stop here and measure the level of radioactivity," he said. We got out of the jeep near the outskirts of Alappat and put our geiger counters to work. They began to give off a high-pitched beep. We calculated the level of radioactivity to be 1.8 rems per year, ten times the internationally recognized public exposure limit.

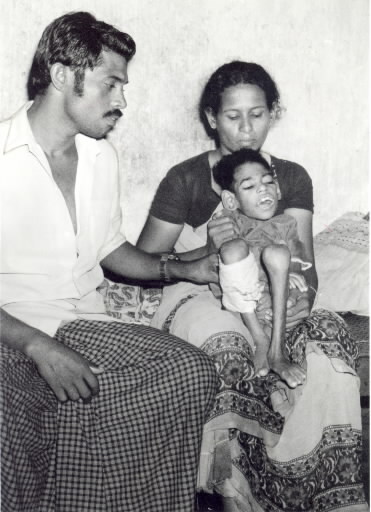

We traveled a little further down the expanse of glittering black sand to the village and pulled up at one of the houses there. The whole place was no more than ten or twelve yards square. As we entered, immediately in front of us we saw a small girl asleep in bed, her mouth hanging open. She was very thin, and her legs were twisted. Her name was Asha and she was seven years old. "The only thing Asha understands is when she is hungry..., " the girl's mother, Viswhawma, said, looking sadly at her daughter. "We have to feed her on soft food like milk and bananas—rice is too hard for her to chew," her husband, Raja, added. The strain of looking after her daughter was apparent on Viswhawma's face.

The couple started to notice something odd about Asha when she was about eight months old. She had hardly grown at all, and she never made a sound. The child began to suffer from frequent bouts of fever, until she was spending all her time in bed. A terrible suspicion took hold of Raja and Viswhawma; their eldest daughter had shown exactly the same symptoms before she died in 1985 at the age of six. The local doctor told them that Asha's condition was due to a congenital disease, but was unable to pinpoint the cause. The couple could not think of anything either.

They heard the word radiation for the first time recently, but were not aware of what it could do to the human body. "Even supposing it was dangerous," said Raja, "this village is the only place for us." He looked down at his daughter and added, "I wonder how long she will be with us." His wife's eyes glittered with tears.

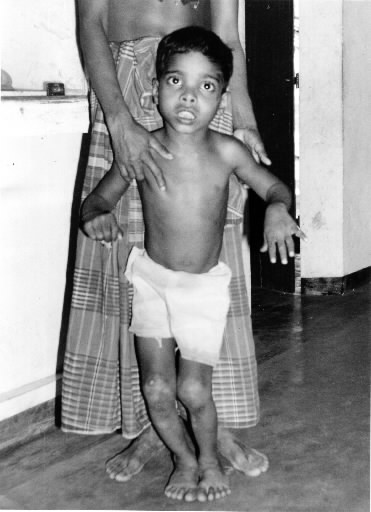

We left their home wishing there was something we could have said or done to comfort them, and walked around the village. There seemed to be an unusual number of disabled people in Alappat; we saw people with deformed shoulders, children with multiple disabilities, a child with Down's syndrome, three out of five children in one family had badly impaired vision. We found ourselves wondering if such a concentration of disabled children and young adults in one area was due to exposure to radiation.

Four villages, home to a total of fifty thousand people, lie within this area of high natural background levels of radiation. In 1977, the All India Institute of Medical Sciences of New Delhi conducted a comparative survey of thirteen thousand people living in a highly radioactive area and six thousand people living in areas with acceptable levels of background radiation. The results showed that while the highly radioactive area included twelve children with Down's syndrome, the other area had none. The number of severely mentally and physically handicapped children in each area was twelve and one respectively, and that of patients with unidentified illnesses, eleven and three. In short, the institute found major differences between the two areas. Furthermore, the report stated that genetic defects were far more frequent in the high-level radiation area.

Representatives from the government-sponsored Bhabha Atomic Research Center in Bombay disagree and insist that there is no greater incidence of illness or disability among residents receiving high doses of radiation in that area than anywhere else. Padmanabhan dismisses their claims as part of the myth of safety promoted by the Department of Atomic Energy, and criticizes the Bhabha Center for not carrying out a thorough enough survey. He also criticizes the survey of the Institute of Medical Sciences as not giving a clear overall picture of the situation, especially with regard to the incidence of radiation-related diseases.

In order to fill in the gaps left by these previous surveys, the Center for Industrial Safety and Environmental Concerns launched an epidemiological survey in March 1988, covering a total of ninety thousand people; all the families in the high-level radiation area, plus forty thousand people from neighboring areas with normal levels. Padmanabhan told us that he expected different results from the data obtained from research on Hiroshima and Nagasaki victims, because the people were exposed to radiation in a different manner. Victims of the A-bombs in Hiroshima and Nagasaki were bathed in a huge quantity of radiation for a second, but the people of the radiation coast are exposed to radiation throughout their entire lives. Padmanabhan also plans to invite experts from the United States and Japan to help analyze the data and assist in producing a plan of action to save the people from any further harm.

Keywords

Monazite was first discovered on the coast by a German in 1909, and in 1912 a British company began extracting the mineral, continuing to do so until the end of the Second World War. At that time, this area produced half of the world's output of monazite. In 1948, a year after independence, the Indian government established the Department of Atomic Energy and banned the export of monazite, hoping to use the thorium-232 in it as nuclear fuel. In 1950, the company Indian Rare Earths was formed and two years later it began extracting thorium at a refinery in Alwaye, ninety miles away from Quilon City.

India boasts the largest deposits of monazite in the world. The company refines three thousand tons of ore per year, and is thought to have a stockpile of between three thousand and thirty-five hundred tons of thorium for use in the future as nuclear fuel. The Department of Atomic Energy had planned to bring a number of fast-breeder reactors using thorium for fuel into operation by the 1980s. However, this plan is running a long way behind schedule, and, at present, demand for thorium on the domestic market is way below their expectations. Fortunately for the Indian government, the rare earths found in monazite have recently begun to be widely used by developed nations in high-technology industries such as electronics, which has lead to an increase in demand. These rare earths have become a valuable foreign exchange earner, and thorium has dropped to the status of a byproduct.