2. Hazardous Smoke Detectors

Mar. 25, 2013

Chapter 5: Britain and France

Part 2: French Duplicity

Part 2: French Duplicity

Our next stop was the resort of Nice in the south of France, where we spoke to Nicole Jammet in her apartment on the sixth floor of a high-rise block overlooking the sea. Mrs. Jammet had lost her husband, Yves, to leukemia seven years previously, and was now living alone.

"Where shall I start?" she began, gazing out of the window at the azure sea. "My husband was a pilot in the air force. He was a military man through and through—even if he had felt the slightest bit of dissatisfaction with the military he would never have said so."

In contrast to her slight frame, the man in the photo was tall and well built. After leaving the air force he had worked as an electrician in a private company for five years, and in 1972 he went to work at the navy missile research facility in Chateauroux in central France, where, according to his widow, he had been exposed to radiation when he was made to clean smoke detectors.

The smoke detectors in question used americium-241, which gives off alpha rays. The alpha rays cause an electric current to be set up which is broken by contact with smoke, thus acting as an alarm. However, when this substance with a half-life of 433 years makes its way into the human body, it accumulates in the bones and bloodstream and is likely to cause cancer.

Yves Jammet knew that opening the detectors and cleaning them was dangerous. He also knew that they were supposed to be sent back to the manufacturers for repairs. No matter how many times he told his superiors that it was not only dangerous but against the law for the detectors to be opened, he was continually ignored.

"It was three years after he started work there, that he began to complain of being tired all the time. Yves had never had a sick day in his life up until then," his widow continued. "Two years after that we found out that he had leukemia." After several months spent in and out of hospital, Yves Jammet died in February 1982. That same day his wife discovered the connection between the smoke detectors and her husband's death. She found his work schedule on the bookshelf next to the bed.

"It had written in it which officers had ordered him to do repairs and things like that. When I read that book I realized that smoke detectors had killed my husband."

The Ministry of Defense recognized Yves Jammet's death as being work related, yet they urged his widow to sign a document stating that his death was "nothing out of the ordinary." Shocked by such blatant deceit on the part of the military, Nicole Jammet took the Ministry of Defense to court. A verdict was handed down in her favor in 1988. However, her husband's former employers have appealed this decision, and she has yet to receive any compensation.

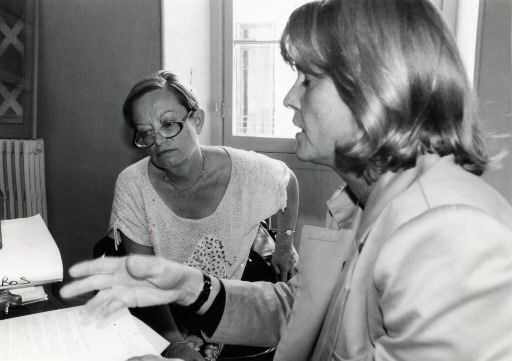

Mrs. Jammet's lawyer, Vladimira Giauffret, whom we talked to in Nice, had harsh words of condemnation for the ministry's actions. "The reason they ignored Yves' pleas to take him off dangerous work was that they were more concerned about their budget than the health of their employees. Their refusal to pay out compensation springs from the same motive: if they pay one lot they will be swamped with other claims."

Giauffret then told us about another case which concerned a man who came into contact with radioactive substances when he was in the army. Like Yves Jammet, this exposure to radiation eventually caused leukemia and he died leaving a wife and three children. Also, as in Jammet's case, the army recognized his death as work related but refused to take responsibility. Giauffret summed up the situation succinctly: "The military gets nervous at any mention of radiation."

Until her husband's death Nicole Jammet had never doubted the military's judgment on anything. The last seven years have changed all that. "If Yves had not left that work diary, I would have been none the wiser," she said. "Now I feel I must continue the fight for the sake of those in the same position as myself."