2. Low Wages and Low Safety Standards

Mar. 26, 2013

Chapter 6: Brazil and Namibia

Part 2: Namibia’s Uranium Mines

Part 2: Namibia’s Uranium Mines

The company is equally well aware of the weakness of the workers' position, and conditions at the mine are inferior, with almost no protection against radiation.

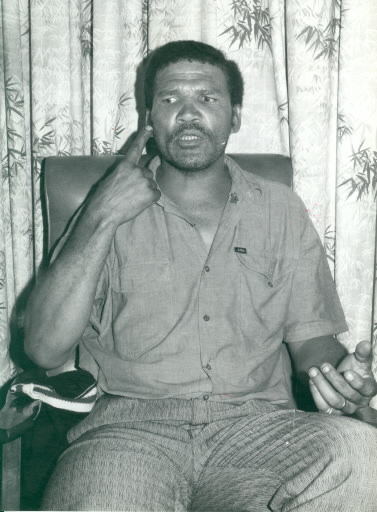

When mining began in 1976 the workers were provided with accommodation less than three miles from the mine, in the middle of the desert. We spoke to Clement, who had worked at the refinery's acid plant ever since the mine opened. Holding his hand to his throat, he spoke in a husky whisper. "Our rooms as well as our bodies were constantly covered in dust. It would've been bad enough if it was just from the desert, but there were huge clouds of it from the mine as well."

At the time the workers' living quarters were segregated: in total there were 1,500 black workers, 1,000 Coloureds, and only 200 whites. All the buildings were brick, but there were clear differences in the areas allotted according to race. The white workers had large kitchens and living rooms, while the black and Coloured workers camped in small rooms housing between six and eight men. Moreover, the accommodation for black and Coloured workers was surrounded by a wire fence and guarded by patrols, making it seem more like a prison than company housing.

"The whites lived like kings compared to us. All we got was a bed and a chest of drawers. The married men had to leave their wives and children at home, of course; the place couldn't really be called 'company housing,' it was more like a camp." Clement showed us a photo taken in his room in 1976, and sure enough, the only extra piece of furniture to be seen was a portable radio.

The miners now work eight hours a day and get two days off a week, but when the operation first started they were working twelve-hour days. Despite these long hours, their wages were still less than half of those of the white workers. At that time wages were paid on an hourly basis, so if the black and Coloured workers wanted to increase their incomes they had no choice but to work themselves to exhaustion. This hourly rate was calculated according to experience, and ranged from about fifty cents to U.S. $1.20. Even Clement, who was a fit worker, was only ever able to earn $135 a month. Although prices of everyday items were low, it was still far from enough to support a decent standard of living. Compared with other workers in Namibia, the miners were relatively well paid, but most of the men were sending a large part of their pay home and scraping by on very little themselves.

In addition to the inferior accommodation and low wages allotted to them because of their color, the workers at Rossing were kept completely in the dark concerning the dangers of radiation. They were told that X-rays and gamma rays penetrate the body, but were assured that uranium did not contain sufficient quantities of these to make it dangerous. The company only made the wearing of film badges compulsory in 1979, three years after operations began, and then only in the final stages of the uranium oxide extraction process.